Art in architecture

A tete-a-tete with world renowned architects Christopher Benninger and Ramprasad Akkisetti on their world of Architecture which is woven in art, poetry, heritage and nature

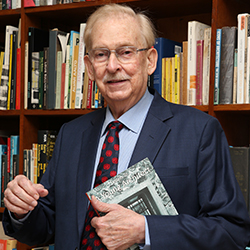

Christopher Benninger, Founder Chairman and Principal Architect along with Founder Managing Director, Ramprasad Akkisetti, have founded the Christopher Charles Benninger Architects (CCBA) Designs.

Christopher Benninger stands as an eminent figure in the world of architecture, renowned for his innovative designs and profound impact on the built environment. Born on 30th June, 1942, in Hamilton, Ohio, Benninger's journey in architecture has been marked by a relentless pursuit of excellence and a deep commitment to social responsibility. His architectural philosophy is deeply rooted in the belief that buildings should not only be aesthetically pleasing but should also serve a higher purpose in the context of society.

Benninger's career is a testament to his diverse influences and experiences. He began his formal education at the University of Florida in the United States, where he was exposed to the teachings of the renowned architect, Frank Lloyd Wright. This exposure left an indelible mark on Benninger's design sensibilities, as he integrated Wright's principles of organic architecture into his own work. Following his time in the U.S., Benninger journeyed to India in the late 1960s, a move that proved to be pivotal in shaping his architectural vision. Immersed in the rich cultural tapestry of India, he drew inspiration from its traditional architecture, while also incorporating modern design elements.

"Architecture is the art of creating poetry from the sights of nature and the arrangement of buildings, a process I refer to as choreography"

- Christopher Benninger

One of Benninger's significant contributions is the establishment of the "Center for Development Studies and Activities" (CDSA) in Pune, India in 1976. This institute reflects his commitment to addressing societal challenges through architectural solutions. The CDSA serves as a hub for research and development, focusing on sustainable and contextually relevant planning and architecture.

Ramprasad was pursuing his career in medicine at the Armed Forces Medical College (AFMC) in Pune when he met Benninger. Ramprasad learnt the art and science of design from Benninger and became an able compatriot of Benninger. Both of them created a stir with their maiden project, the Mahindra United World College on the outskirts of Pune, known for the stamp of architecture which is artistic and close to nature. Since then, the duo has travelled the world over, designing for prestigious projects for the government and patrons of art. Ramprasad is also an avid art collector and has conceived some brilliant art canvases.

Here, they provide an insight into their tremendously talented journey where the story of every project is a tryst with art, culture, heritage and nature. Read on…

Corporate Citizen: You (Christopher) are originally an American from the USA but migrated to India in 1971. What tempted you to come to India, which then was known as the land of snakes?

Christopher Benninger: Luck smiled upon me—by the age of 28, I had earned a master's degree from Harvard University and completed another at MIT. However, I began to sense a homogenisation in America—the packaged appearance of food at shopping centres, the pervasive branding and so on. Having achieved my academic and professional goals, having been a tenured professor of architecure at Harvard for a few years and traversed the globe, I found myself pondering, "What next?"

It was then that I turned my gaze to India—a land of excitement and new adventures. India became the canvas on which I could discover my true self, a place where I could truly make a difference. Unlike the predictability of an American life with its comfortable yet monotonous routines, staying in India presented a monumental challenge. Here, one could confront the vast opportunities and hurdles, striving to leave a lasting impact rather than conforming to a placid existence until the end.

The Road to India

At 28, fresh with a master's degree in Urban Planning from MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), I arrived in India with a vision to establish a school of planning. In Gujarat, there were only a handful of individuals with qualifications in Urban Planning—a Chief Town Planner for the entire state and another with a PhD in road design focused on highways. Surprisingly, no one was willing to initiate a school dedicated to planning.

Undeterred, I took the initiative, founding what is now the esteemed Faculty of Planning at CEPT University, Ahmedabad. Over the years, it has grown into the premier school of planning in India and I remain an active member of its board. My journey with this institution dates back to 1968, marking a thrilling and enduring commitment. It's an accomplishment I believe would have been challenging to replicate in any other country.

India, with its unique blend of vast development opportunities and a robust democratic framework, provided the ideal environment. Here, we embrace open ideas, lively debates, and discussions—a country where contentment seems widespread, if you were to inquire.

"Architecture stands as a unique storyteller of history. Unlike other historical records, it provides tangible insights into the past"

- Ramprasad Akkisetti

CC: You (Ramprasad) were studying medicine in AFMC, one of the most glorious medical institutes but you dropped that and came to do the framework of buildings, so what tempted you to get into this field?

Ramprasad Akkisetti: The dual reasons for my departure from the field of medicine were rooted in a persistent inclination towards art and design. During my student years, the prevailing choices for those excelling in academics were limited to either engineering or medicine. Although I cannot attest to the current landscape, I believe present-day students have a more diverse array of opportunities beyond just engineering and medicine.

Despite securing an impressive All India Rank, I pursued medicine, opting for the Armed Forces Medical College (AFMC) for two compelling reasons. First, education there came at no financial cost, and secondly, upon completion, I would earn the title of a doctor and a Captain in the Armed Forces—a notion that held a certain romantic allure at the time, in early 1990's.

Upon my arrival in Pune, I devoted two or three years to my medical studies at AFMC, receiving a stellar education. I cannot disregard the excellence of my professors and the overall quality of the college. However, a turning point in my life arrived when I realised that the medical profession did not align with my true passions—art, design and culture.

The Turning Point

A particular Sunday remains vivid in my memory. I remember, I was taking a break because we were only allowed to go out on weekends and holidays being in the academy. So I came to the bus stop near AFMC around 4pm, I got onto the bus only to know that it was the wrong bus and then that wrong bus took me instead of Mahatma Gandhi Road to Deccan. I went to Deccan and I had just enough money to return, so I asked the conductor, “Where is this area?”. He said, “This is Deccan”, and I said, “I wanted to go to Mahatma Gandhi Road”. The conductor replied, “But you are on the wrong bus”. Then I asked him, “You know my hostel’s mess closing time is 8 pm and we don’t get any dinner after that. So when does this bus turn around?” and he said, “In 30 minutes it will turn around”.

So, I figured, why not make the most of my time on that Sunday afternoon at 4 o'clock? Taking a leisurely stroll, I found myself at Sambhaji Park. I entered right as the gates opened, making me the first person there for the evening. As I meandered through, I settled on a bench, and that's when I encountered Christopher Benninger.

In the quiet of the park, Christopher and I were the sole occupants. As I sat, he struck up a conversation, inquiring about my origins and what I was pursuing as a career. I said, “I am from AFMC.” Recognising this, Christopher remarked, "Oh! You're from the medical school?". To which I confirmed with a "Yes". Names and contacts were exchanged and later, I visited his CDSA institute.

Upon touring the center, I found myself at a crossroads—whether to continue on the path of becoming a medical doctor in the Indian Army or to embark on the career I had always envisioned. In that moment, I made the choice to drop out and initiate a brand new journey alongside Christopher. Three decades have passed since that decision, and throughout this time, I have passionately pursued my chosen path to build a practise.

In our architectural endeavors, we've established clear roles—Christopher oversees the design aspects, while I take charge of everything else beyond his purview.

"I regard architecture as “frozen music” and the foundational art form— the mother of all arts"

- Ramprasad Akkisetti

CC: What is the definition of an architect and how have you innovated and turned architecture around?

Christopher: Architecture, at its core, is a form of technology, primarily concerned with crafting shelters that serve various functions. Anyone can operate at this functional level and become an architect.

However, I believe true architecture transcends mere functionality; it is the art of creating poetry from the sights of nature and the arrangement of buildings, a process I refer to as "choreography."

Comparable to a film sequence, it involves introducing characters, progressing through different scenes, and engaging with evolving activities. This choreography transforms your movements, your persona and your thinking.

CC: Could you tell us about your maiden project, the architecture of Mahindra United World College in the outskirts of Pune?

Christopher: When envisioning Mahindra World United College, my initial sketches portrayed simple boxes placed amidst the scenic backdrop of the Sahyadri mountains. Positioned amidst jagged peaks, with a view of Mulshi Lake from our centre, I aimed to make the buildings mirror the natural contours of the mountains. I envisioned structures that not only provided views to Mulshi Lake and the surrounding mountains but also utilised the mountains as a form of "borrowed landscape". This concept involved integrating the mountains into the campus's overall landscape, creating a harmonious blend.

Another conscious decision was to utilise locally sourced materials like Basalt Stone and tile roofs. In my view, architecture is akin to poetry, advancing technology while infusing it with emotion. It goes beyond solving functional space requirements; it transforms the way people experience life. Unfortunately, many buildings today merely serve as technical solutions to functional needs, lacking the poetic essence that true architecture can bring.

A Kaleidoscope of Architectural Choreography

CC: What is your idea of architecture which you have successfully pursued with Christopher Benninger?

Ramprasad: In 1995, Mahindra World College marked the commencement of our professional journey—a pivotal moment considering the concurrent opening up of India. This period saw the formation of numerous companies and our collaboration on Mahindra World College held significant national importance. Reflecting on this project, two profound aspects of architecture come to mind.

Firstly, it underscores the deficiency in our education system, particularly in neglecting aesthetics, art, and the finer aspects of life. As one grows wealthier, an appreciation for these elements deepens. I advocate for an educational paradigm that begins with cultivating an understanding of aesthetics and artistic nuances.

Consider, for instance, our inclination to visit places like Agra primarily to witness iconic structures such as the Taj Mahal or Madhurai for the Chola Meenakshi Temple. This exemplifies how architecture plays a pivotal role in shaping tourism and travel experiences. It prompts the realisation that education should encompass an appreciation for architectural aesthetics from the outset.

Secondly, architecture stands as a unique storyteller of history. Unlike other historical records, it provides tangible insights into the past. While you may not know the specifics of the food consumed 5000 years ago, architectural remnants offer a glimpse into the living spaces of that era. Recognising the profound historical significance of architecture is crucial, yet it is a facet often overlooked in our society. Understanding and valuing architecture is essential for a more comprehensive appreciation of our cultural and historical heritage.

Architecture transcends the mere categorisation of 2 BHKs and 3 BHKs; it is the medium through which emotions evolve, cultures take shape, and individuals undergo personal development. Whether manifested in an educational institution or a residence, be it a house, I consistently convey to my clients that these structures are more than just physical spaces.

When discussing housing units or buildings intended for people to inhabit, I emphasise to clients that, beyond selling a 2 BHK or a 3 BHK, they are essentially shaping the environments where future generations will be born and raised. The design, layout, and ambiance of these spaces play a crucial role in influencing the emotions, familial connections and societal bonds that will unfold within them. Architecture, in this context, becomes a profound force in shaping not only physical spaces but the very fabric of human experiences.

In essence, I regard architecture as "frozen music" and the foundational art form—the mother of all arts. It sets the stage for everything that follows, influencing our education, shaping our lives and leaving a lasting imprint on the way we perceive and interact with the world.

"Architecture is akin to poetry, advancing technology while infusing it with emotion. It goes beyond solving functional space requirements"

- Christopher Benninger

CC: You (Christopher) mentioned that architecture is not just about cement and bricks but it’s also about poetry, but what about sustainability, especially against the backdrop of climate change a lot of things are about sustainability, which includes architects primarily. Could you just elaborate on sustainability and architecture?

Christopher: Sustainability, when viewed in a comprehensive light, is synonymous with prioritising the well-being and comfort of individuals, encompassing elements such as fresh air, abundant sunlight, and factors contributing to the overall quality of life. A hallmark of commendable architecture lies in its capacity to deliver exceptional ventilation and establish a seamless connection between individuals and the natural environment.

In all our architectural pursuits, we adhere to a consistent principle: the segregation of vehicles from the campus. Whether it is Mahindra United World College or the Bajaj Institute of Technology, a deliberate decision is made to restrict the entry of cars onto the campus grounds. This strategic choice aims to preserve public spaces and promote a harmonious integration of nature with the constructed environment. The aspiration is for occupants to glance out of their windows and be met with the serene presence of nature.

While these considerations hold significant importance, it is noteworthy that, in many architecture conferences, individuals often discuss these principles without first-hand experience in implementing them. This disjunction between theoretical discussions and practical application can be disconcerting, and I find it somewhat disheartening.

CC: You (Christopher) are doing some great architecture even in a poor country like Burundi in Africa as well as in the upcoming democracy of Bhutan. It’s so humbling to know that you are also going to such countries to improve the environment or the landscapes. So talk a bit about both of these.

Christopher: In 1979, my involvement with Bhutan began at a time when it ranked among the ten poorest countries globally, possibly the very poorest. In the capital, electricity was a luxury, available only from 6 to 8 pm, powered by generators. It became evident to me that working with economically challenged communities posed a significant challenge, yet it also presented a unique opportunity for substantial transformation. Bhutan, from being one of the poorest nations, now boasts the highest per capita income in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) regions, signifying a remarkable turnaround.

My engagement in Bhutan extended beyond conventional architectural roles; it involved strategic planning. A pivotal moment occurred during discussions around the Bukhara when the Planning Committee brainstormed ways to bring about radical change. Recognising their unique asset - abundant rivers and water, they conceived the idea of generating hydroelectricity. In collaboration with the Japanese on the 'Chuka' project, I played a role in envisioning Bhutan's shift towards generating and selling electricity to India and Bangladesh, ultimately transforming the country's economic landscape.

Tryst with Burundi

Fast forward to my recent interaction with Burundi, a country that has progressed significantly beyond Bhutan's early challenges. Burundi now possesses electricity, automobiles, television, and other amenities that were once distant dreams for Bhutan. During our recent visit, we engaged with the country's leadership, including the President, the head of the Senate, and the head of the Lower House. The prospect of constructing the parliament complex in Burundi signifies more than physical infrastructure; it symbolises the establishment of the rule of law—a critical element in reducing violence and fostering democratic governance.

Having been involved in similar projects, such as building provincial capitals in Sri Lanka during the early 1980s, I recognise the ongoing struggles in these regions. The excitement lies in being part of visible development, witnessing transformative changes unfold before one's eyes. In contrast, developed nations like the USA may lack this dynamic quality as everything appears to have already been accomplished. For those seeking excitement and adventure, I encourage exploration in places like Burundi in Central Africa, where the spirit of change and progress is palpable.

"Painting is more than creating aesthetically pleasing images; it's about storytelling. Timeless stories grace the walls, columns and ceilings of temples, carrying societal narratives, cultural insights and the wisdom of life"

- Ramprasad Akkisetti

CC: How do you construct in a nation where every architectural endeavour must align with the heritage norms of that country?

Ramprasad: We're tasked with erecting contemporary structures, modern buildings tailored for present-day functions. The challenge lies in infusing these structures with an identity factor, as they play a pivotal role in embodying the national identity. Take for instance, a country's parliament house, a symbol that represents its identity and conveys an image to the global community. This undertaking involves navigating the complexities of adhering to the country's heritage, contending with budgetary constraints and projecting a message to the world that signifies arrival and identity, much like a national flag.

In building the Parliament House of Burundi, our challenge extends beyond mere geography awareness. We strive for it to be recognised not just as a physical location but as a structure possessing a distinct identity. Granting identity to a building stands as one of the architect's foremost responsibilities and is a significant challenge that we must adeptly navigate.

CC: You (Ramprasad) studied medicine in the medical college but here you were with a walking talking encyclopaedia of architecture, how did you learn from him? My question is to Christopher as well, how did you accept a novice and make him into such an expert?

Christopher: I've worked in some of the world's most impoverished nations, where starting with virtually nothing and building something significant is truly exhilarating.

On a more serious note, what immediately impressed me about Ramprasad from day one was his inclination to question my work. In my studio, where I'm often considered the master of architecture, the Guru, few dare to question my decisions. I've even urged young members to critique my work, to call it 'scrap' if they believe it is, but they hesitate.

Ramprasad, even at a young age, consistently challenged and questioned my approach. He'd ask, "Why are you doing it this way? There might be a better way." It's this willingness to question, characteristic of a young mind, that drew me to him.

In our global travels and collaborative projects, our discussions were not mere tours or photo sessions admiring landmarks like the Taj Mahal. Instead, we delved into studying and questioning each project. Ramprasad's readiness to ask probing questions made him stand out in my eyes, a quality I found rare in others

Ramprasad: Learning, for me, extends far beyond the pages of books, especially because Christopher has been my default Guru. Through osmosis, I've imbibed knowledge from him—from our conversations and his writings, including letters I've helped draft or type. This method of learning, reminiscent of the traditional Guru-Shishya Parampara, involves disciples living and learning with their teacher and eventually developing their own identities

CC: You (Ramprasad) are so meticulously organised and studied medicine which is all about following scientific system so how come you are also an art collector and an artist?

Ramprasad: Art has been an integral part of my life from the moment I can remember; it's a constant presence around me and within me. During my youth, as a student and a child, I found myself naturally adept at it, effortlessly getting lost in the process. This early passion led me to advocate for choosing a career that one truly loves, eliminating the fatigue associated with a typical 9-to-5 job. However, upon co- founding the firm with Christopher, my role as a full-time artist or painter took a backseat.

My childhood experiences, particularly the nightly storytelling sessions with my father, left an indelible mark on me. His captivating narratives, often derived from English novels, served as a wellspring of inspiration. I utilise these stories to shape the narratives, such as the one inspired by Banaras. While visiting the Ghats of Banaras, I pondered how to create a distinctive painting that transcends conventional depictions. The answer lay in the 16 Sanskaras of Hinduism—chapters representing the lifecycle of an individual under Sanatan Dharma. Transforming these chapters into a 2-D image proved challenging but rewarding, resulting in what could possibly be the world's largest miniature painting, featuring nearly 3000 human figures.

To infuse diversity into these figures, I ventured into the old city of Pune, photographing over 600 people to capture a range of faces for the painting. This meticulous process aimed to represent real individuals in the miniature style, transcending the repetitive patterns often found in such art.

For me, painting is more than creating aesthetically pleasing images; it's about storytelling. Timeless stories grace the walls, columns and ceilings of temples, carrying mythical tales, societal narratives, cultural insights and the wisdom of life. Having explored temples, mosques, churches and more worldwide, I've come to appreciate the role of paintings as crucial documents of life's varied facets. They immortalise habits, traditions and stories, offering a unique perspective on the rich tapestry of human existence.

CC: You (Christopher) are 80 years old and Ramprasad is 52, so do you think that Ramprasad has taken the legacy forward and how do you see your vision in the next 50 years?

Christopher: I believe Ramprasad comprehends the evolving landscape of India. Over the past five decades, my focus in architecture has been primarily on institutions, but lately, we've ventured into housing. Ramprasad, I believe, can steer the company into new realms, particularly recognising the increasing demand for housing in the next 50 years, especially in the next decade. Recently, we've taken on projects for Forbes families, designing factories that double as artistic spaces, earning accolades for their innovation.

Ramprasad is positioned to lead not just within our studio but on a broader national scale. Cities like Kolkata are inviting us to design structures akin to the unseen Belmondo, and Ramprasad is at the forefront of these initiatives. The architectural studio we run needs to adapt to the changing times, and it's an opportune moment for someone like him to take charge.

A hallmark of commendable architecture lies in its capacity to deliver exceptional ventilation and establish a seamless connection between individuals and the natural environment

- Christopher Benninger

Ramprasad: Legacy poses a significant challenge in creative fields, where each person's creative talent is unique, be it in fashion design or art. It's rare for someone to match or surpass the achievements of their predecessors. Understanding that I cannot fill Christopher's shoes, I've discerned the trajectory of India's growth in the next two decades, which is expected to outpace the previous 20 years. Fast growth begets a different clientele, prioritising functionality, durability and speed over timelessness.

While recognising that the forthcoming era may not demand timeless buildings, we remain committed to building structures that stand the test of time. Whether Christopher is involved or not, we aim to cultivate the habit of precision, ensuring our creations are not mundane but enduring, sustainable, and tailored to meet the demands of our clients in this dynamic and fast- paced era.