Walking alongside the last foot soldiers of THE FREEDOM MOVEMENT

After all, their sacrifice and struggle were the fuel that fired the war for Indian independence. They are the last remnants of an age—where youth was dedicated to the service of the country by the hundreds of thousands. While most are long gone, a handful are still alive.

In their nineties now, the 15 chronicled in P. Sainath’s book The Last Heroes: Foot Soldiers of Indian Freedom are valuable for not just for the stories they tell, but the values they represent. Values that motivated the freedom struggle, values enshrined in the Indian Constitution, values that remain timeless and time-tested.

Well-researched and evocative, the narrative is nevertheless lucid and easy to read. A precious work that highlights the role of ordinary people in the defeat of colonialism.

In Pune to discuss his motivation for writing the book, P. Sainath was in conversation with noted writer and critic Latika Padgaonkar—a fine backdrop for the Corporate Citizen review of a book that tells a story worth remembering on the 76th anniversary of Indian independence.

“We fought for two things—Freedom and Independence. We attained Independence.”

- Captain Bhau, Ramchandra Sripati Lad, Leader of the Toofan Sena, Kundal, Sangli

Simple words that encapsulate a not-so-simple struggle. After all, freedom and independence often tend to be distinct entities and not synonyms for each other. In 1947, India got its official independence and soon became a sovereign entity. But the fight for freedom—from tyranny, inequality, top-heavy distribution of resources, poverty and corruption—is an ongoing, continuous process—something the freedom fighters understood over the decades it took the newly independent country to come into its own.

By freedom fighters, Sainath points out, he means the foot soldiers of the struggle—the unsung heroes, the ones who built the edifice of a monument that was then bejewelled by the chosen handful—the great men, who truth be told, relied on the common folks to be the wind beneath their wings. (Think: Mahatma Gandhi without the thousands who followed him or Netaji Subash Chandra Bose without his cadre, or the mesmerised youths who hung on to Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s bidding.)

A life not that ordinary

As Mahatma Gandhi himself said in his 1931 letter from Yerawada jail: “Great men seem to be the cause of revolution. In truth, the people themselves are the cause.”

They are the ones who really spearheaded India’s freedom struggle. The millions of ordinary people—farmers, labourers, homemakers, forest produce gatherers, artisans and others who stood up to the rapacity and cruelty of the British Raj. People who never went onto be ministers, governors, presidents, or high-ranking public officials, who were never mentioned in the history books or for that matter even in the government pension lists. But that hardly mattered to them. “We fought for freedom and not pension,” they pointed out with a dignity that belied their poverty.

The men, women and children featured in the book are from all backgrounds: Adivasis, Dalits, OBCs, Brahmins, Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus. They hail from different regions, speak different languages and include atheists and believers, Leftists, Gandhians and Ambedkarites.

Despite the differences, they had one thing in common: an opposition to the notion of Empire that was fearless and uncompromising

"It is unfair to say that we looted the money. It was Indian money that we took back from the British. The money we lifted from that train did not go to any individual’s pocket but to the prati sarkar or provisional government of Satara. We gave that money to the needy and the poor."

- Captain Bhau,

founder of the Toofan Sena

“It was important to get the voices of the ones still alive—most of them are in their nineties—for just a few years down the line, they will no longer be there to tell us their story,” Sainath told the audience. “It would be a pity if these voices are lost, because the post-1947 generations need these stories. I managed to reach 15—of whom the oldest are 102 and 92. But it was worth the trouble. To learn what they understood. That freedom and independence are not the same thing—and how to learn to make those come together,” he said.

The Corporate Citizen review

This book is a work of both head and heart. By head, we mean Sainath’s formidable writing skills and scholarship that make this a gem. By heart, we mean the sheer love and effort devoted to bringing the multiple voices together in a single work. Sainath’s was an arduous task—given that the book is pillared by the oral testimonies and stories narrated by freedom fighters from remote parts of the country. Many of them were interviewed more than once to fully comprehend the import of their words.

What adds to the book is Sainath’s prose that is elegant, refined, simple and to the point, with a fine ability to capture mood, convey poignancy and inadvertent humour. Such as the story of Hausabai Patil from Sangli. Both she and her drunken “husband” staged a fight before the small police station at Bhavani Nagar, Sangli. The husband thrashed her mercilessly. Still, the cops continued to ignore them until such point that the man picked up a large stone to kill his wife. That’s when they came rushing out. After all, goes the acerbic sentence, “ A woman being beaten by her husband in public was okay with them. But having to explain a murder right in front of their station could prove embarrassing.” The couple continued to fight; the policemen counselled the couple at length and scolded them; brokered a sort of peace and escorted the two to the railway station. “Go home to your village,” they commanded the pair, fed up with the drama. Now the couple protested they had no money. That problem too, the police solved, by placing two tickets in their hands, and once again appealed to both of them to reconcile with each other.

However, they were to return to a very different kind of spat; one which allowed for no reconciliation. In their absence, Hausabai’s comrades had looted the police station, picking up the rifles and ammunition kept there; the very reason why she and her fake husband had staged the literally painful drama in the first place. Hausabai mentions how annoyed she continues to be 74 years later with the fake husband for beating her so hard to make the fight look genuine. “It really hurt,” she said with a laugh.

Speaking of Hausabai, it must be noted that women were as much part of the freedom struggle as men—“whether or not the bureaucratic pension lists mention them,” said Sainath. As Laxmi Panda of Bhubaneshwar who asked in anguish: “Because I never went to jail, because I trained with a rifle but never fired a bullet at anyone, does that mean I am not a freedom fighter? Many fighters of the Indian National Army didn’t go to jail. I worked in INA forest camps that were targets of British bombing. Does that mean I made no contribution to the freedom struggle? At 13, I was cooking in the camp kitchens for all those who were going out and fighting, was I not part of that?” She eventually got her freedom fighter status and the meagre pension that went with after the persistent efforts of ex-INA officers, now holding public office.

Still, that didn’t do much to alleviate the reality of her life.

She declined an invitation from the Odisha governor and his wife to attend the Republic Day function in Bhubaneshwar. Neither did she join them for tea the next day. Employed as a domestic help, going to the function meant a loss of pay. And she had a good laugh at the “parking pass” thoughtfully included in the invitation. “The last time I had anything to do with a car was when my late husband was a driver. That was four decades ago,” she smiled.

Some fought with unusual weapons: like Mallu Swarajyam who decimated her enemies with the sling-shot- a nasty looking rope and leather contraption—the use of which she demonstrated to a twenty something audience consisting of techies, in a Hyderabad auditorium. Having introduced the weapon and explained its uses, the octogenarian freedom fighter began twirling it above her head with power and ease. “That’s how we took on the Nizam’s police,” she said. The audience burst into applause and gave her a standing ovation. But Mallu Swarajyam wasn’t there for the applause. She exhorted the assembled young techies to fight, as she had, for a better society. One that valued equality and justice.

The slingshot was my weapon, the cell phone and the laptop are yours, as are so many technologies I cannot even name.

- Eighty plus Mallu Swarajayam to a roomful of 20 somethings

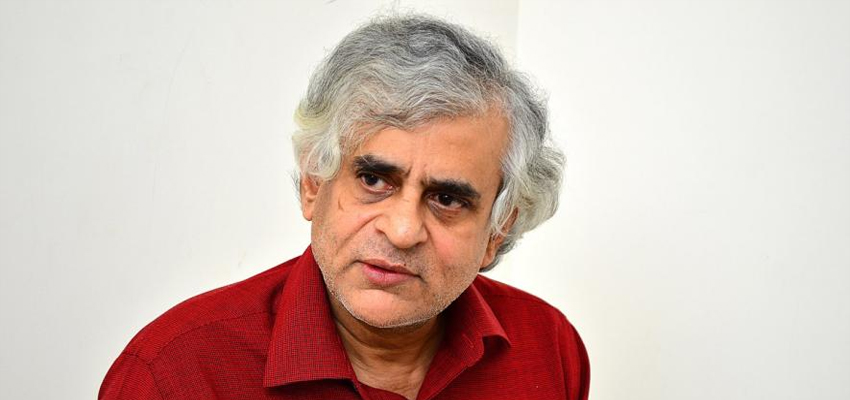

THE AUTHOR AT A GLANCE

Winner of the Ramon Magsayay award, P. Sainath is a reputed journalist and scholar. He is also, the founder- editor of People’s Archive of Rural India or PARI. His last book Everyone Loves a Good Drought is a critically acclaimed work.

Then she stunned the audience again with her knowledge of the world around her, despite not being educated. “People like you have been at the forefront of the Occupy Wall Street Movement. There is so much you can achieve if you fight. The slingshot was my weapon, the cell phone and the laptop are yours, as are so many technologies I cannot even name,” she said as the auditorium roared with thunderous claps.

Considering that we live in times where political leanings have polarised families and continues, it is worth pointing out that these freedom fighters were firm believers in the unity of diversity. As the revolutionary Bhagat Singh Jhuggian of Hoshiarpur (not to be confused with the legendary martyr Bhagat Singh) said in his testimony that the communal violence he saw in his village that lay alongside the bloodied border of India and Pakistan, it was a travesty of justice to watch families that had co-existed alongside each other for generations murder each other in the name of religion. Similarly, Baji Mohammed who had tirelessly worked for resolving Hindu-Muslim disputes at local levels in independent India, shares his deep-seated sorrow at the growing distrust between the communities. “This wasn’t Gandhi’s vision,” he said simply.

Others like Captain Bhau or Ramchandra Sripati Lad of Sangli founder of the Toofan Sena that carried out several revolutionary activities and looting of a British train on June 7, 1943. The amount looted was Rs 19,175—a whopper of a sum in those days. That was the year of the Great Bengal Famine. And though other regions did not suffer the murderous price rise that Bengal did, they were strongly affected too. Yet, even in a spectacularly high price year like 1943, the money looted from the train could have purchased over 60,000 kg of rice in the Bombay Presidency. The Toofan Sena were to make even more deadly strikes in less than a year. “It is unfair to say that we looted the money. It was Indian money that we took back from the British,” he said sharply. “The money we lifted from that train did not go to any individual’s pocket but to the prati sarkar or provisional government of Satara. We gave that money to the needy and the poor.”

"When the police tried arresting us, I said: I am the magistrate. You take orders from me. If you are Indians, obey me. If you are British, go back to your own country."

- Chamaru Parida, Panimora village, Bargarh, Odisha

"We, as soldiers of freedom, love action, and in the action of the most honoured are those who either achieve martyrdom in the field or at the gallows. But they are only the gems on the top of a building. They only enhance the beauty of the building. But the stones that make the foundation are much more important. They strengthen the foundation and provide long life to the building. It is they who carry the burden for many years."

-Shahid Bhagat Singh

What stands out from the stories is that while the participation of people in different parts of the country was influenced by the reality of their existence, cultural practices and ideological leanings, they were part of a larger conscience. Like the time when the people of Tamil Nadu mourned the execution of Shahid Bhagat Singh (a denizen of the North.)

As Latika Padgaonkar summed up in the session: “Each story is heartening and memorable. The last lines of each chapter are particularly poignant and sum up the essence of the freedom fighter beautifully. Of Baji Mohammed, Sainath writes: Just a gentle old man with a charming smile and a sacrifice that sat lightly on his ageing shoulders. And of Hausabai, he says: A foot soldier of freedom and not fanaticism.

In these jaded times, how desperately we needed this reminder.