MARCH 2022, 1,698 GIRLS WERE ADOPTED FROM THE AVAILABLE POOL OF 2,991 DOMESTIC (IN-COUNTRY) ADOPTIONS IN INDIA.

A closer look at the 2013-14 and onward data by the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA) shows that more girls in India were pledged for adoption than boys. In a country where female foeticide is a common offense, and sex-determination laws are often disregarded in favour of the ‘blue’ gender, the new ‘pink’ preference is a silver lining to changing societal mindsets. The noticeable mindset change amongst parents in adopting girls has been substantial for the past 8-10 years. But the other reality is that there are many more abandoned girls at birth than boys, and they are more likely to become a part of the greater adoption pool. However, increasingly educated, urban parents have been making informed decisions to adopt girls but not as the last resort option or a biological failure to have their own. The awareness of the social disadvantages accorded to an abandoned girl child in India also prompts parents to seek a girl child. Many prefer not to have biological children of their own, and many couples with one child adopt a girl child as the second one. However, a fear amongst adoptive parents of boy children is the reaction they might get at an older age if their truth is revealed. Contrarily, a girl child is considered to be more caring. “The preference for girl child adoption is especially higher in Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu [Chennai], and Karnataka [Bangalore]. In these places, the waiting period for a baby girl could run up to six years across private adoption agencies. I know people who have looked elsewhere for adoption because of the long waiting time. However, suppose you go up north, to Haryana and Punjab. In that case, the trend evens out, and the number of parents who want girls and boys is equal,” said Mini Nair, a child counsellor, and psychotherapist associated with adoption agencies. It’s time to heal society and make amends for the many “pink buds” nipped for want of a male progeny.

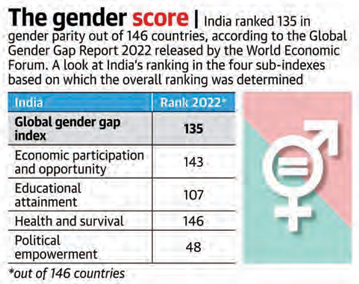

CORPORATE CITIZEN SLAPS THE ABYSMAL GENDER GAPS THAT CONTINUE TO DOG INDIA’S 662 MILLION FEMALE POPULATION IN HEALTH, ECONOMIC PARTICIPATION, OPPORTUNITY, EDUCATIONAL ACCOMPLISHMENT, AND POLITICAL LEADERSHIP.

India is ranked 135th among 146 countries in the 2022 - World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI), just five ranks higher than the previous 2021 ranking, which brings little cheer. On the health and survival subindex, India ranked the lowest at 146th place, with gender gaps larger than 5% and pooled with Qatar, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, and China. The WEF’s GGGI reported that India has fallen behind even Bangladesh (71), Nepal (96), Sri Lanka (110), Maldives (117), and Bhutan (126). In South Asia, countries that were worse off than India are Iran (143), Pakistan (145), and Afghanistan (146). Bangladesh has been designated the most gender-equal country in South Asia for the 8th consecutive year. Several other reports corroborate India’s low female gender dynamics. The India Skills Report 2021 observed that 51.44%women are more employable than men in India, but their workforce participation rate has been a measly 33% in 2022. The impact is age-old, with most women employed in the informal sector and dependent on regional variations. Notably, women with self-savings accounts have increased to 78.6% due to the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana, but with an ever-shrinking workforce participation. However, a respite in the GGI Index records that the percentage of legislators, senior officials, and female managers increased from 14.6% to 17.6%, and women professionals and technicians increased from 29.2 to 32.9%. Since the release of the last GGGI index, India has shown some marginal improvements, which consciously hints that policymakers need to pump efforts into women-centric incentives. Once again, the apparent path is for women’s representation in leadership positions at all levels for better job and resource accessibilities. But can the administration look beyond offering token leadership offices? Can the government manifest more promising policies and social incentives to help women overcome the economic and deep-rooted socio-political dogmas?