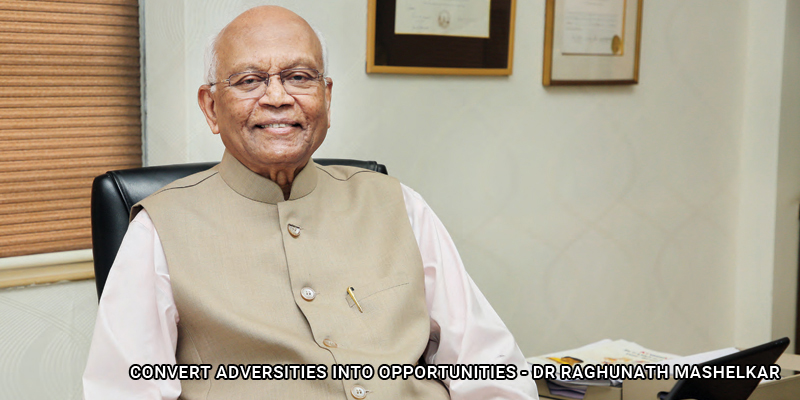

Dr. Raghunath Mashelkar The Evergreen Optimist

Dr. Raghunath Anant Mashelkar is known for his world-class scientific research, transformative science and innovation leadership. His pioneering of different movements in India, ranging from traditional knowledge protection to the creation of strong yet balanced IPR systems, to inclusive innovation based on the concept of Gandhian Engineering. He has been an influential thought leader in shaping Science, Technology & Innovation policies in post-liberalised India.

In the corporate world, Dr. Mashelkar has been on the Board of Directors of several reputed companies such as Reliance Industries, Tata Motors, Hindustan Unilever, Thermax, Piramal Enterprises, KPIT Technologies, Godrej Agrovet. He promoted innovation in the corporate world. He chaired Reliance Innovation Council, KPIT Technologies Innovation Council, Thermax Innovation Council, Persistent Systems Innovation Council, and Marico Foundation’s Governing Council. He currently chairs the New Energy Council of Reliance, which is making multibillion dollar investment in the total value chain, ultimately aimed at becoming one of the world’s highest producers of green hydrogen.

Dr. Mashelkar has been decorated with three of the highest civilian awards - Padmashri (1991), Padmabhushan (2000) and Padma Vibhushan (2014). He has received a record of 45 honorary doctorates from universities around the world. He has been the largest serving head of three major organisations, namely. Director General of CSIR (1995-2006), Chairman of the National Innovation Foundation (2000- 2018), and President of the Global Research Alliance (2007-2017). He has been the President of the Indian National Science Academy (2004-2006) and the first and only non-English President of the prestigious UK Institution of Chemical Engineers (2007) since its foundation.

Dr. Mashelkar’s connections with the international academic and research community are deep and wide. He has been a Visiting Professor at Harvard University (2007-2012), at Delaware University (1976, 1988), and at the Technology University of Denmark (1982).

In this insightful interview, he makes a case for thinking big and dreaming big for the nation, pursuing it with single-minded determination, being part of the solution, not the problem, and being ever optimistic - the mantras for his success…

Corporate Citizen: You love to call yourself as a dangerous optimist’. Could you expand on that?

Dr Raghunath Mashelkar

Dr Raghunath MashelkarDr Raghunath Mashelkar: There are always two ways of looking at a glass half filled with water. One looks at it as a glass half full or a glass half empty. I have always looked at it as a glass half full, and one must be thankful to God for what he has given us. I also have this particular attitude that even in adversity I see an opportunity, and I have converted adversities into opportunities all my life.

I’ll give you an example: I was invited by Delhi University’s (DU) Physics Teachers Association for an inauguration. There was some turmoil then in DU for which they had planned a morcha after the event. Somebody said, “Ladies and Gentlemen, we are in a coma. Dr. Mashelkar will tell us what to do.” I had 10 seconds to think. I said, “I have never addressed 500 people in a coma so far. But perhaps what was meant was not that you are in a coma, but that you are at a (grammatical) comma. With a comma, you have a sentence that is incomplete. You are taking a pause, but the rest of the sentence can be positive. The next one can be positive, the paragraph can be positive, the page can be positive and the chapter can be positive. You can have a complete change.” Then they said that since Dr. Mashelkar had talked about coma and comma, could they rethink their strategy? The rest of the discussion was positive. A single statement had turned the mood around.

The human mind is like that. I have always had this particular attitude. On my 60th birthday, the National Chemical Laboratory (NCL) felicitated me and a lot of eminent people came to give talks. One of them was Narayana Murthy, who is an old friend of mine. He said, “Ramesh (Dr. Mashelkar is known by this name with close friends) is always positive. I rarely get depressed, but if I do, Sudha (his wife) tells me, why don’t you call Ramesh?” So this has been my trait and it comes from within, because being positive changes the entire world. Sometimes people say it is dangerous to be so optimistic. But what people have found is that what I say today does happen after 10-20 years. So some say, “He gives us dreams and aspirations, which seem impossible at the time he gives them, but they actually happen.” That is the dangerous optimism part of it.

CC: In this world of negativity, how do you inspire youngsters?

The current generation wants to be successful, but very quickly. What they need to understand is that there is instant coffee, but not instant success. There is no substitute for hard work. I always tell them to work hard in silence and let success make all the noise. I will be touching 80 years soon, and I have worked day after day for decades. Purpose, Perseverance and Passion, these three things matter.

You have to have a big purpose in life, not just for your career and bank account, but for the society and nation. You must never quit. Winners are never quitters and quitters are never winners. And whatever you do, you must do it with passion. The third thing is, don’t get frustrated. If the doors don’t open, create your own doors. Then I give them an example.

When I returned to India in 1976, India was a poor country with $100 GDP per capita, as against $2000 GDP per capita now. We did not have enough foreign exchange. My research required imported equipment. I wanted to create a school on polymer science engineering, and that door was not opening. It would take me two years to get it. Do I fold my hands and sit for two years? I wasn’t getting the equipment, but God has given me his own equipment - my brain. So I shifted to mathematical modelling and simulation. That does not require imported equipment. Even an ordinary computer would do. It turned out to be such breakthrough work, that I was awarded the S S Bhatnagar prize. I started the work in 1977, I got the award within five years, in 1982. This is the highest award in the category. When you can’t build a highway in time, you should create by-lanes because they are quick. That has been my approach all the time. Try to be a part of the solution. If you are part of the problem, you will become cynical, and negative and get depressed.

"The current generation wants to be successful, but very quickly. What they need to understand is that there is instant coffee, but not instant success. There is no substitute for hard work. I always tell them to work hard in silence and let success make all the noise. I will be touching 80 years soon, and I have worked day after day for decades. Purpose, Perseverance and Passion, these three things matter."

- Dr Raghunath Mashelkar

CC: You said the flight of imagination has no limit. What exactly do you mean?

There is a saying in Marathi “Je na dekhe Ravi, te dekhe Kavi”. Meaning, what the sun can’t see, the poet can. Dream, and dream big. I took over as the Director of NCL in 1989. This was two years before India liberalised. Till that time, research was all about import substitution. Copying products available abroad and making them cheaper. So all you thought about was how fast could I copy a product. You were not thinking big at all. My challenge was that we had breakthroughs that were ahead of the times, but when we went to the Indian industry, I would get questions like “Has the US or Europe done it?” That was the mindset of a follower, not a leader. So I had no chance to go ahead of the world and do ‘Forward Engineering’. I was only doing ‘Reverse Engineering’.

On my very first day (1st June 1989), at 11 am, I addressed the entire staff. There were 11000 people. I said, let NCL become an international chemical laboratory. I said we should be able to export our knowledge to the western world, to the big MNCs. This was a crazy thought. This was my flight of imagination. If I had to license a technology, it had to be patented. The situation was such that CSIR, in its 39 years of existence, did not have a single US patent. Here I was, being dangerously optimistic, saying that such a laboratory will one day say that it would license its patents and be the best in the world. I remember a young scientist coming up to me. I told him that we should be able to think ahead of even global companies like GE. He said to me, “Sir, are you aware that their budget is two and a half times India’s R&D budget?” I told him that it is not the power of the budget that matters, it is the power of the idea that matters. I said that since he talked about GE, we would take on GE.

GE was producing an engineering plastic called polycarbonate. They were world leaders with 40% market share. I had some idea about polycarbonates, based on the work I was doing, on solid state polycondensation. This was something GE had never done. I discussed this idea with my colleague, Dr. Sivaram, who later on became the Director of NCL. We got a breakthrough, which had a big impact.

I remember when I said that we will become an International Chemical Laboratory, we did not have any technology officer or publicity agent. I took on that role. I started marketing NCL. I remember going to the US on invitation from GE, and giving a talk.

We had filed for a US patent by that time, and it was even granted. They were very surprised, and they saw that despite being market leaders, they had never thought of this process, but who was this person who had put a flag in their territory? They were impressed but they also wanted to validate the results. They sent a team of four people to NCL and they were amazed to see the capacity we had. Then they wanted to give us a contract for doing research, and they thought that since India is a poor country, they could do this very cheaply. I quoted a number. They were shocked. They had come via Russia. USSR was crumbling at that time. They said that for that price, they could buy a Russian lab. I said please go buy it. You will not get what I am offering, and I said I charge not by man hours, but by brain hours. I sent them back, yet they came back. We then partnered, and licensed a three years patent to them in 1992, for close to 1 million dollars. That money would be 10-15 million dollars in today’s money.

This was the first instance of reverse transfer of technology. We had always been beggars and borrowers of technology until then. For the first time, we started exporting our technology. It had a lot of interesting impact because Jack Welch said that if they are so good in India, why aren’t we there? It was then that he decided to put up an R&D centre in Bengaluru. That was the beginning of India’s emergence as a global R&D platform. When GE came, others started coming.

When you go to GE’s R&D centre, you will find a conference room named after me. In fact, on the inauguration day, Jack Welch had asked me to join him. That flight of imagination of wanting to turn NCL international, of taking on the world leader and creating something which they had not thought of, that is what I meant. If you aim at Everest, you will reach Kanchenjunga, but if you aim for Kanchenjunga, you won’t even reach Hanuman Tekdi. If you aim at Hanuman Tekdi, you will remain where you are.

You have to have a big purpose in life, not just for your career and bank account, but for the society and nation. You must never quit. Winners are never quitters and quitters are never winners. And whatever you do, you must do it with passion."

CC: Tell us about your childhood.

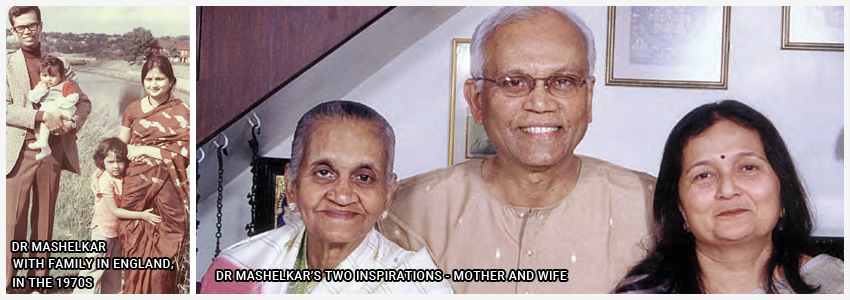

It was very rough. My father died when I was six years old. I was born in a village called Mashel. My mother could barely read or write. She wasn’t absolutely illiterate, but she had no formal education. She brought me to Mumbai, and did odd jobs like stitching to bring me up. Two meals a day was a challenge. I walked barefoot till I was 12 years old.

CC: How did your mother have the vision to take you and come to Mumbai?

I had a maternal uncle who used to work at a paint shop and painted buses in Mumbai. He brought us there. My mother had a great influence on my life because although she wasn’t greatly educated, she set standards for me. For mathematics, I used to get 100/100 most of the time. Sometimes, I got 97. I was happy. She made me sit and asked me where I lost the three marks. That was the kind of standard she set for me.

I went to a municipal school called West Khetwadi Upper Primary School. This was a Marathi medium school. After 7th standard, I went to a secondary school called Union High School. The interesting thing is that in the 7th standard, I stood first in class with 87% marks, but we required Rs 21 as entrance fees. My mother didn’t have it and it took her a long time to gather that money, so I lost admission to good schools. Union High School was a school for the poor. I got admission there, but that school had very rich teachers and one of them changed my life. This is the importance of teachers.

My science teacher’s name was Bhave. He later became the Principal. He believed in his students, not rote learning. He advocated learning by observing, doing, and listening. He would take us on a tram to the Hindustan Lever factory. At that age, we saw how soap was made. We went to a company called Vimco in Ambernath to see how matchboxes were made. This was my first time travelling by train and he paid for my ticket because I had no money.

One day, he took us out in the sun and said that he wanted to show us how to find the focal length of a convex lens. The experiment he did was a simple one. He took a convex lens, he waved it around in the sun, and where light concentrated the brightest, he explained that that was the focal length. We tried this on a piece of paper and after some time the paper burnt. When that happened, he turned to me and said, ‘Like this lens, if you focus, you can achieve anything in this world.’

This did two things to me. It showed me that Science was so powerful. So I would become a scientist. Secondly, it gave me the philosophy of life, that no matter what happened, you had to focus, concentrate. Before the lens acts to concentrate the sunlight, the sun’s rays are parallel, and parallel lines never meet. But the lens makes them meet. So I coined the term convex lens leadership. Convex lens leadership is one where you are dealing with different languages, religions, and cultures, basically a divided society. Then you get a convex lens leadership which gets people together. Unfortunately, concave lens leadership is what we are seeing today.

"I coined the term convex lens leadership. Convex lens leadership is one where you are dealing with different languages, religions, and cultures, basically a divided society. Then you get a convex lens leadership which gets people together. Unfortunately, concave lens leadership is what we are seeing today."

CC: What do you think about the state of pure sciences in our country, and why do youngsters hesitate to pursue them?

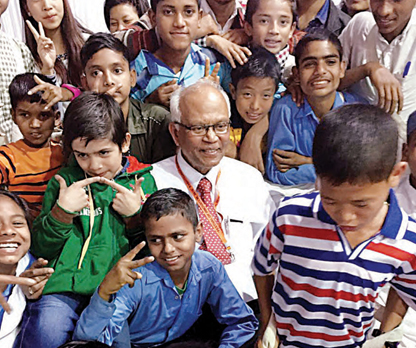

You must make science enjoyable. You must show that science is not all about mugging up formulae, but about having fun. Education is all about learning, doing, and being, and there is no substitute for doing things by hand and exploring. When I was a member of the Prime Minister’s National Innovation council, the challenge was that children were into mugging knowledge and not into creating innovations. We created what we called ‘tod, phod, jod’ centres. The Congress government fell in 2014, and the new government also liked the idea and called it ‘Atal Tinkering Labs’. This was one of the government’s most successful programmes and is still operational. This has been extended to hundreds of schools now. Children have the opportunity of enjoying what they do.

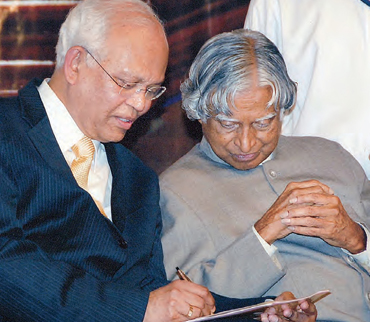

The most important part is the School. Children are moulded in schools. Science must be made an attractive career to encourage budding scientists. Let us not forget that Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam was a scientist. Scientists have occupied the highest positions in this country. This sends a good signal to students.

CC: We have such excellent scientists in this country, but do you think that the government and the media do not do a good job of highlighting them?

The fault lies on both sides. Scientists are poor communicators. I have seen this. In fact, Dr. Jayant Naralikar, in his book ‘Scientific Edge’, has listed the top 10 achievements of science and technology in India. The 10th one he has listed is the transformation of CSIR under me. There are a number of angles to that transformation. Communication was one of them.

We addressed it by telling society, telling politicians, what we were doing. It brought a lot of benefit to CSIR. When CSIR celebrated 60 years in 2003, I asked my colleagues what we should do to mark it. One said we should highlight 60 accomplishments. I said let’s do something innovative that will capture the public’s imagination. So we had an exhibition of 60 technologies, but the advertisement in the paper to mark the anniversary didn’t talk about them. We took an entire blank page and on it, there was only a finger, and on that finger was election ink, which was made by CSIR. The indelible ink we use is made by CSIR. The text was ‘CSIR technology on every finger’.

When I asked them to create that ad, they pulled out a beautiful finger and put ink on it. I said no, I wanted a rustic-looking finger of a farmer. Sudheendra Kulkarni, who was with Atal Bihari Vajpayee ji, told me that Atalji was having breakfast and going through the newspaper when he saw this ad. He asked what it was and Mr Kulkarni explained it to him. In the afternoon when we had the celebration, Atalji gave a speech. He put his prepared speech aside and spoke extempore about technology and democracy. He said this was a technology that was protecting democracy. This simple communication idea created such an impact. Scientists must learn communication as a course because, in the end, that is often times what matters. Now startups are learning this fact because they have to pitch their technology in five minutes.

The media is also to be blamed because science does not appear on the front page, it appears on the corner of some inside page. Science correspondents are not properly trained nor are they properly paid. Why would a young fellow have an aspiration to be a science correspondent? But Covid changed the perspective a lot. I said in my speeches that 2020 won’t just be remembered for Covid alone, but for Indian science. When Covaxin came, it was our own vaccine. It was made possible by the work put in over the years. We should be very proud of our accomplishments.

CC: Tell us about your Gandhian Engineering.

In 2008, I was the first Indian to be honoured as a Fellow by the Australian academy. I felt that they were honouring me when there were a hundred more qualified people from India who deserved this more than me, so they probably didn’t know much about India. So I titled my talk, ‘Gandhian Engineering’. There was a mystique about the talk itself because they had never heard of the term ‘Gandhian Engineering’ before. Gandhiji had two tenets. The first was ‘There is enough in this world for everyone’s need, but not for everyone’s greed’. Therefore, when you have non-renewable resources, don’t exhaust them. Keep them for your grandchildren. His second was, ‘The benefit of science should reach all’. This became ‘more from less for more’. That became the MLM Mantra and it became famous across the world.

Making high technology for the rich is easy. Making low technology work for the poor is also easy. But, making high technology work for the poor is not easy at all. Getting more from less is difficult. Once you get more from less, the technology is available for more and more people. For example, breast cancer treatment is expensive. We have an award winning creator, Mir Shah, who has created a kit for a $1 to detect breast cancer. This is high technology, but at $1 per kit, it can work for the poor. ECG is a lengthy process and expensive. One creator has created a pocket ECG where you place your two thumbs in the machine for 15 seconds, and then place the machine below your heart and repeat. The results are sent to a smartphone app. This costs Rs 5 per ECG. This is Gandhian Engineering which can benefit the poor.

There is another technology called ‘Save Mom’. It is a wearable device which looks like a bangle. It can measure seven parameters in a pregnant woman and her health can be monitored. Today this has gone to 100 villages. This test costs Rs 1000 per 1000 days, i.e., Rs 1 per day. During the peak of the pandemic, people were dying in ambulances because hospitals were full. Some people converted their bed at home into a hospital bed, where they could measure these seven parameters at home itself through this device.

"When you can’t build a highway in time, you should create by-lanes because they are quick. That has been my approach all the time. Try to be a part of the solution. If you are part of the problem, you will become cynical, and negative and get depressed."

CC: Can you tell us about the gap between academia and the industry?

The issue is that academia likes to explore new ideas and create new inventions. Inventions are nothing but the demonstration of a new idea. To turn that idea into a commercial product is a new journey. There are many things involved in that. So how do we bridge that gap? When I created the New Millennium Indian Technology Leadership Initiative, I brought 100 private sector companies together from Day 1, so that there was a partnership from the beginning.

CC: You are a director at Reliance Industries. What do industries need to do to uplift an entire community from poverty?

Dr Mashelkar with President, Dr Abdul Kalam

Dr Mashelkar with President, Dr Abdul KalamReliance is a great company. I call it the exponential inspirator. Exponential, the way it grew after being started by the late Dhirubhai Ambani. He was a petrol pump attendant in Aden, in Yemen. He came back and started selling sarees. He then created Vimal, then looked into what goes into making sarees. The answer was polyester. Then he looked into how polyester was made. He went into petrochemicals. How are petrochemicals made? From oil refineries. He went into oil refineries. Where does oil come from? He went into exploration. Today, their refinery, located at Jamnagar, is the biggest refinery in the world.

In the news you only read that Mukesh Ambani is the richest man in Asia. You don’t see what he has done for the poor. For example, when he created Jio, this lifted India into Digital India. I was the Chairman of the Reliance Innovation Council. It had Nobel laureates and some of the greatest thought leaders in the world on it. But he never publicised this fact. Secondly, he is audacious in his thinking. His thinking is limitless. One day he and I were having a talk after a board meeting. He told me, Doc, we must leapfrog. I said, Mukesh, do you know why a frog leaps? A frog leaps because he is afraid of the predator. As a reaction he jumps to safety. Should we be doing that or should we be pole vaulting, with only the size of the pole determining the size of your aspiration and how far you can go? He loved the idea, and we created a programme called ‘Beyonders’. This was for young people who were capable of thinking beyond limits. That became the spirit of the organisation.

CC: How do you make technology accessible to the masses?

If you see, in Feb 2017, we were 155th among 236 nations in mobile data consumption. That is almost at the bottom. Within no time, we did not leapfrog from 155th to 100th, we pole-vaulted to the No 1 position. We are No 1 in the world today in terms of data consumption. Why could he do that? Because he brought down the cost of data to Rs 4 per GB, which is the cheapest in the world, so that the poorest of the poor can afford it.

Dhirubhai had once said that he wanted people to make a phone call at the cost of a postcard. When I came back to India in 1976, it used to take 6 years to get a phone, and then there would be a pooja and a party to celebrate the occasion. Today the poorest of the poor have a phone. Mukesh made voice free. Data was for Rs 4 a GB and voice calling was free, which is why he has half a billion customers today. That has created enormous benefit for the poor. The poor today are able to connect with one another on Whatsapp, get information about weather, farming, news, etc.

I’ll tell you a touching story. The deaf and dumb talk to each other through sign language, but they can’t do that until they see the other. Now because data is so cheap, they are able to make video calls and communicate on mobile. This is called inclusive innovation.

CC: Can you tell us about the Crazy Idea fund and other such initiatives?

There is no limit to human imagination. You have to dream. I started this fund in NCL. I wanted breakthroughs coming out of India which the whole world would emulate, instead of the other way round. That cannot happen until you take risks. I said, let us pick up ideas where the chance of success is one in a hundred. I will fund it. I was essentially funding failure. When I went to CSIR, I changed the name of Crazy Idea fund to New Idea fund, because the Parliament was just one km away, and they might object as to why public money was being spent on something with that name.

Then later on, at the national level, I created the New Millennium Indian Technology Leadership Initiative, where the targets were similar. For example, in June 2020, there were so many children across the country who didn’t have access to either smartphones or tablets and they couldn’t go to school and learn. But what if the devices were affordable, then they could have afforded them. I had a programme in the New Millennium Indian Technology Leadership Initiative, where I said that a laptop costs $2000, can you make it in $200. I am a 10x guy, which means I want things 10 times cheaper yet 10 times better.

"If you aim at Everest, you will reach Kanchenjunga, but if you aim for Kanchenjunga, you won’t even reach Hanuman Tekdi. If you aim at Hanuman Tekdi, you will remain where you are."

CC: Do you see the industry and governments rising up to the challenge? What is holding us back?

Dr Mashelkar with young winners,

Dr Mashelkar with young winners, at the National Foundation’s Awards in 2016

Vinay Deshpande from Bengaluru actually had created a laptop for that amount. But to manufacture it, you require the industry to come forward to take the initiative. You need the government to come forward to place initial orders. This was in 2005. You can imagine that if it was manufactured at that time, today that price would have come down to $30-$40. We have to have trust. The one message I would like to give is that it is the tripod of talent, technology and trust, which needs to happen. We have all the talent in the world, we have access to technology, but we must have trust.

I will tell you a story. I hope you never had Dengue. If you have it, it takes one or two days to diagnose and also to find out at what stage it is. Navin Khanna has generated a kit where within 15 minutes, you can know whether you have Dengue or not. This was patented, USFDA approved, but nobody bought it. Because we were importing it from the US, Australia and South Korea. Then there was a Dengue pandemic. Children started getting infected. The government was in panic and they placed orders with these countries. Two of them couldn’t deliver so fast. South Korea said they could, so we placed the order, but they loaded those cases on the wrong ship which went to Africa. We had no kits left at all. There was no option but to turn to Navin. At that time, his market share was 0%, today it is close to 80%. Imagine if the ship from Korea had come at the right time, we would still be importing them. That’s what I meant by there being Talent, Technology but in this case, no Trust in our own people’s ability.

There is a caricature by R K Laxman, where an eye doctor is examining the patient, and he says ‘Sir, there is a particle in your eye, should I take it out? I am asking, because it is a foreign particle.’ Today, I very proudly say that we aren’t a Start-up nation, we are a Starting-up nation. We aren’t like Israel, but look at our performance. Until 2019, we had 1 unicorn per year. Now we have 44 Unicorns in 2021, which is one per week. This is happening because young entrepreneurs are getting digital access.

CC: What is your philosophy of life?

To bring a smile on the face of 9 million people, not just a select few. That is through the work that I have done, giving access equally despite income inequality. That is my dream. Whether you call in inclusive innovation, more from less for more, Gandhian Engineering, innovation compassion and passion, there are many ways to describe it, but it is about creating an equal and equitable society, and using technology for making that.