Exploring Mercantile Bombay

Why has Mumbai always attracted the entrepreneurial spirit and what makes it a money magnet? The discussion on ‘Mercantile Bombay: A Journey of Trade, Finance and Enterprise’, based on the book by the same name by Sifra Lentin, sees an expert panel discuss Mumbai’s commerce and culture, ports, migrants, finance, its rich mercantile history, and how it helped develop a multicultural city. Moderated by Mini Menon, author, co-founder and editor, Live History India), the panel comprised Sifra Lentin, author and Bombay History Fellow at Gateway House; Dr Rashna Poncha, Associate Professor, History Department, Sophia College, and Bazil Shaikh, Author and former central banker. The discussion was presented by Gateway House Mumbai, Live History India and Avid Learning.

"Mumbai is a crown jewel of India that attracts many star-crossed dreamers. What makes it so attractive? What makes the city the financial capital of the country? Today’s session will cover why migrants chose this city, the trade wars, the fallout of the American civil war, and how rivalries between local rulers, colonial powers, and merchant families shaped these tiny islands into India’s most important port city and financial capital,” said Asad Lalljee, SVP, Essar Group and CEO of Avid Learning, at the start of the session.

Mini Menon: Trade, finance and enterprise – these are the three pivots around which the city has been shaped and continues to get shaped. Why did the port of Bombay stand out and become an epicentre when there were so many other ports on the Western coast?

Mini Menon

Mini Menon

Sifra Lentin: Bombay was the most important city east of the Suez. It grew into a financial centre in the late 19th century, much before other cities like Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Dubai. Some of the factors that contributed to its growth include the fact that Surat, as a port city, started declining. After the death of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, subsequent rulers began farming out the most productive Surat mint. Surat was prone to attacks. There can be no business where there is instability. So, the East India Company began looking for an outpost that was outside Surat but close enough to it, and shifted headquarters to Bombay in 1678. The Portuguese had realised the strategic importance of Bombay, but they were already in decline at that point and didn’t want to put in the effort to develop it.

What was the new community structure like?

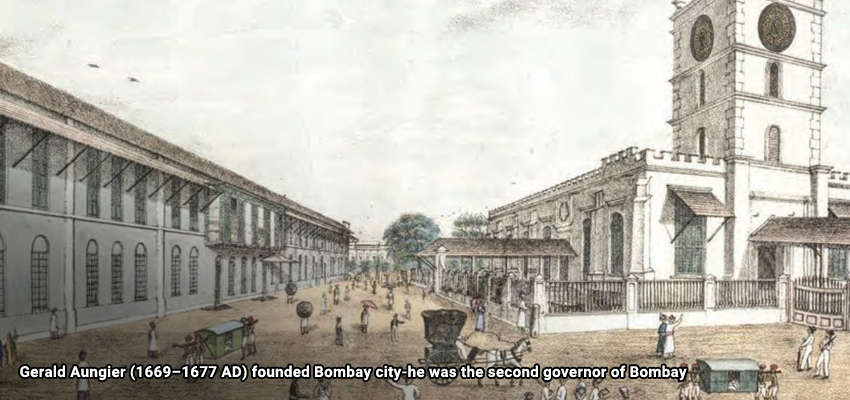

Dr Rashna Poncha: At that time, Bombay was comprised of small fishing and agricultural hamlets. It was Sir Gerald Aungier, the second East India Company (EIC) governor, who realised the value of this place, unlike the Portuguese who held it for 150 years and didn’t do much with it. Aungier expands berthing in the key areas, builds warehouses and courts of law, and invites people to come in and settle. And what does he draw them in with? The promise of religious freedom! So, while there was a lot of trouble on the hinterland, here was an unconnected place, that attracted Parsis, Jews, Armenians, the baniyas from Gujarat to come here and settle. Even at this point, Bombay is a trans-shipment port because it does not have a hinterland—there is nothing coming in from the mainland to Bombay, and the place itself isn’t growing anything; the soil is not good enough. Aungier expanded the population from 10,000 to 60,000 people, centred around the H-shaped island of Bombay. He fortified the Bombay castle, has the Bombay Marine which is helping him protect it from the Dutch and the French. Incidentally, the first Parsis came to Bombay before the English came here—Dorabji Nanabhoy worked here for the Portuguese. But the first real push comes when you have Lowjee Nusserwanjee Wadia coming in. The ship-building yards bring in so many more people. These immigrations happen in waves, which continued post-Independence.

"Surprisingly, for nearly 60-70 years there was no bank in Bombay, despite Bombay picking up with the opium trade, etc. No bank was set up till 1840. It was a paradox of plenty, in some ways. Bombay became slosh with money, especially the supernormal profits of the opium trade, and to use the unfashionable term: primitive capitalist accumulation."

- Bazil Shaikh

With no hinterland, the commercial movement of goods becomes very important, for which finance plays a very big role. What were the early centuries like?

Bazil Shaikh: Since Bombay did not have a hinterland, it relied on the port to serve as a transit and trade point. What was essentially needed was security of person, and security of possessions. You also need an ecosystem where contracts are honoured, or enforced, failing which there is a dispute resolution system. The money made in that area, you should be able to take out or convert wherever you wish to go, at a low transaction cost. Bombay provided these conditions to poach talent, initially from Surat, and thereafter literally from across the world. Talent brings with it capital, and its networks. The role of a credible currency and the convertibility of that currency was very important in taking it forward.

Under Farrukhsiyar, the EIC also gets the mandate to mint the Mughal rupee. How does that impact the movement of money and what does it do to the city?

Bazil Shaikh

Bazil Shaikh

Bazil Shaikh: If there was one big disaster that happened, it was in 1717, when Emperor Farrukhsiyar outsourced the mints to private parties. Till that point, you had a largely uniform currency; there were multiple mints but coins were struck to a stringent, uniform standard. After 1717, there was complete disarray when hundreds of currencies came into existence. The money changers made a lot of money in the process but the transaction costs of the economy went up dramatically. Originally, Bombay had started minting coins in the English standard but none of them were acceptable. The British also went over to Shivaji maharaj to ask if English coins could go current in his domain. However, Bombay came into its own after 1717 because the Bombay mint started striking coins to the exacting standards of the earlier one tola of silver which was being struck. The English, being the commercial company, realised the importance of coinage as an instrument of proclaiming integrity and trust which was very important to them from the point of view of reducing transaction cost. The prestige of the British went up dramatically with the coins struck in Bombay which, incidentally, had the mint name Surat but commanded a premium over the Surat rupee. They were masters at psychology and used money as an instrument to propagate the greater glory of the company.

The Bombay/Indian rupee had a footprint far beyond the subcontinent...

Bazil Shaikh: It piggy-backed originally on the Mughal rupee which had its trade routes to the middle-east, the Gulf regions, and from there, also to East Africa. The Bombay rupee was essentially there from 1717 – 1835; when coinage was standardised in India—it became almost like a trade currency in the entire region. Later, Aden became a British protectorate. In German East Africa, the Germans wanted to introduce the Maria Theresa Thaler which was a very popular coin in those days but the popular opinion wanted the rupee—and you had notes issued in German East Africa, Tanzania, Zanzibar which are designated in rupees. You also had the rupee going right down to Indonesia.

"Bombay was the most important city east of the Suez. It grew into a financial centre in the late 19th century, much before other cities like Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Dubai."

- Sifra Lentin

Bombay became a place which had a whole ecosystem of culture, religion, finance, livelihood coming together. What Bombay would have looked like in the 19th century?

Sifra Lentin

Sifra Lentin

Sifra Lentin: In 19th century Bombay, you had the ‘white town’, which was the British town in the Fort area. You had the Baghdadi Jews, Armenians, and Parsis living within the fort and the native communities largely living in the native town outside. A lot of the profiles of the communities in my book are actually based on field interviews. For example, I visited the Iranian community, the Irani masjid, which is incidentally known as the Mughal masjid in that area because Persian was the language of the Mughal court, which is why it was wrongly identified as the Mughal masjid. Imambara road is where all the Shia communities are, and you have four Shia mosques on that one road. Right at the end, where you have the Iranian masjid, there is a hammam (public bath), which is still in use. Hammam street, within the fort, also indicates that there used to be a hammam there. Every community had its presence in a certain area. In the lane before that, the Khoja housing society as well as their community hall is located. Each community carved out a certain religious and, more importantly, a cultural ecosystem around their religious structures, community structures, schools, and hospitals, whether the Bohra community, the Bene Israel on Samuel street, the Bhatia community in Kalbadevi.

Today, the foreign/ overseas communities, such as the Chinese and Iranian, have reduced but their ecosystem still exists. So, you will find the Baghdadi synagogue, the Armenian church, which has been given to the Syrian Orthodox order. Those with Bombay roots keep coming down in December, January, to visit where their ancestors were.

"It was Sir Gerald Aungier, the second East India Company (EIC) governor, who realised the value of this place, unlike the Portuguese who held it for 150 years and didn’t do much with it! Aungier expands berthing in the key areas , builds warehouses and courts of law, and invites people to come in and settle."

- Dr Rashna Poncha

While on one hand, you have the communities coming in, and the trade progressing, it was also a little volatile on the edges, right? It was a time of raiders, pirates...

Dr Rashna Poncha

Dr Rashna Poncha

Dr Rashna Poncha: Pirates were active along the entire coast—in fact, Malabar Hill was a lookout point—but even before that there were a large number of people hopping across from the mainland because, remember the Thana creek isn’t all that wide. The Siddhis, Portuguese, Marathas all made things difficult. But the main part that the EIC wanted to protect was the Southern part of Bombay, where the port was. Bombay fort was built to protect the town of Bombay. Actually, once it was built, they never really had much trouble again. However, in the city itself they saw problems such as the famous Dog Riots, which happened because the government decided there were too many stray dogs around, and they went around shooting them. Parsis have a belief that the dog will lead you across the ‘bridge’ into the after-life, and they were up in arms against this. Finally, the government gave in on the condition that something was done about the stray dogs, and so the Panjrapole was started to house stray animals.

Two events got Bombay up and running and coming into its own-the opening of the Suez Canal, and the American Civil War. What was that period like?

Dr Rashna Poncha: We need to add one more event—1817, we have the larger presidency being formed and we get the hinterland, the cotton-growing districts of the Deccan. The opening of the Bhor ghat in 1830, allows the cotton to be brought from the hinterland and sent out from Bombay. Bombay’s fortunes change there, even before the civil war. Opium coming from Malwa and cotton coming from the Deccan make everyone here—including the EIC—very wealthy. And then the American civil war changed everyone’s fortunes. It changed Bombay’s physical landscape, because that’s when the fort came down, and everyone has so much money so they want land to build palatial houses. What you see today in South Bombay was created post 1864. The physical landscape changed with all of this wealth flowing in. Despite the crash of the cotton market in which everybody lost fortunes, the opium trade still continued. Many communities had also invested heavily in real estate, which saved them. The opening of the Suez Canal made bringing ships, goods, money, mail, all much faster.

Bombay became a big player in the inter-continental trade. Talk about the formal cross-continental trade banking system that starts being built here...

Bazil Shaikh: The driver for banks is essentially a demand for credit, and the scarcity of capital. Bombay was the place where the first bank—along European lines—was set up in 1720. It had a more or less reasonable existence and faded into oblivion around 1778 or so, ironically at the time when banks started mushrooming in Calcutta and Madras. Surprisingly, for nearly 60-70 years there was no bank in Bombay, despite Bombay picking up with the opium trade, etc. No bank was set up till 1840. It was a paradox of plenty, in some ways. Bombay became slosh with money, especially the supernormal profits of the opium trade, and to use the unfashionable term: primitive capitalist accumulation. Banking along European lines was resisted in Bombay by the local interests, though indigenous banks flourished. However, once the genie was let out of the bottle, so to speak, Bombay became a pioneer for banking. Interestingly, in 1842, you had the bank of Western India set up by Framjee Cawasjee, Jagannath Shankarseth, and other prominent people, which went on to become the Oriental Bank, and later, the Oriental Banking Corporation, which became one of the biggest banks in the world. It straddled the world with operations from San Francisco to Yokohama. It also became the note issue bank in Ceylon.

Bombay was linked with the global marketplace and it continued to do so until 1947. After a break, it resurrects itself in 1990 post liberalisation. Your thoughts on the spirit of Bombay

Sifra Lentin: Speaking from the point of view of the book, when trade is freed up, the old structures, which were there between the 1960s to the 1990s, were dismantled to a great extent. We find that the city is attracting the same consulates which were there in the past, for example the city of Hamburg consulate, the Norway consulates; they were there in colonial Bombay and have now opened in the 2000s. They have come here because of the opportunity for trade. Most had opened as trade commission offices, grew into consulates, and then consulate general. These were the markers that indicated that the city, as India’s financial centre, was attracting international trade, as well as investment in their countries. We have a long way to go but we should think bigger than we are thinking right now.

It is also a city that is constrained… The focus is now shifting to Bangalore for new enterprise, to Gurgaon, the new ports in Gujarat...

Sifra Lentin: There is a distinction here - Bombay is more of a financial and commercial services centre, attracting banking, insurance, accountancy, legal services, stock markets, and more.

Well, the jury is out on that! Let’s wait another 20 years and see which way it’s going.

MERCANTILE BOMBAY: A JOURNEY OF TRADE, FINANCE AND ENTERPRISE

This volume reclaims Mumbai’s legacy as a global financial centre of the 19th to the first half of the 20th century. It shows how Mumbai, or erstwhile Bombay, once served as a central node in global networks of trade, finance, commercial institutions and most importantly trading communities. In doing so, it highlights that this city-more than any other Indian city—still possesses all these virtuous elements making it an appropriate location for a financial special economic zone (SEZ) - an idea shelved temporarily.