Digital Literacy for Rural India

"While it is good to have certified social entrepreneurs working with a good set of skills and knowledge, my advice is that you learn, adopt and implement those skills with a long-term vision. It should never be an escape route from the corporate world or for overcoming boredom or personal incompetencies

-Santosh Phad

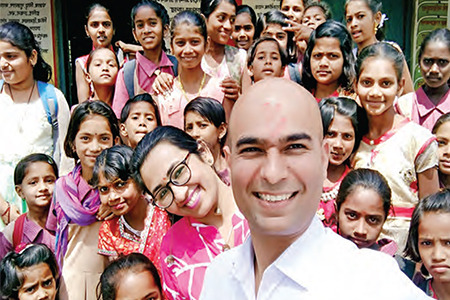

Born to humble farmers, Santosh Phad, Founder and Managing Trustee, ThinkSharp Foundation, began his literacy journey from a Marathi medium, Zilla Parishad school in Mandwa, in Maharashtra’s Beed district. He harboured an undefined childhood passion to do something good for society. Too young to frame his own goals, Santosh followed his parent’s dream to educate their children. The family moved from Mandwa to the nearest Taluka schools in Parli, in search of good quality education and, unknowingly, trod a path void of competent educational infrastructure in the rural belts. The impressions gained during his school and engineering college days, and the beginning of his corporate career in Mumbai instilled a strong desire in Santosh to build a world where rural kids gained the same learning opportunities as their urban counterparts across government schools. He has since bridged the learning and digital divide via his indigenous concepts of Study Malls, StudyFin, and the Digi Library app, impacting 9000+ rural children and 250+ schools across Maharashtra’s 13 districts, also foraying into Gujarat and Chennai

“My vision is to reach as many government schools providing quality education and digital infrastructure to last-mile communities and students. The idea is to offer effective programmes, continuously monitor them, and significantly impact the lives of these children,” said Santosh Digambarrao Phad, Founder, and Managing Trustee of ThinkSharp Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation. It has been developing learning and digital equity across government schools in Maharashtra and is ambitious enough to influence the rest of India.

The Urge to Give

Long before social entrepreneurship prompted corporates to fix their CSR agendas, and propelled media to build a ‘glamour’ coefficient around it, a young Santosh harboured a latent desire to rise above his rustic difficulties and do something for society. He experienced a lack of quality educational resources in the rural confines of Maharashtra’s Beed district. His experience at the local Zilla Parishad school was no different from the Taluka schools at Parli, especially as his family had moved from Mandwa in search of a better education.

“Both the Zilla Parishad and the Taluka schools were the same; and conducted under the trees. There were barely any classrooms available and we would be fortunate if we got a chance to sit in a classroom,” said Santosh. His third school move during his senior secondary days (Grades 11th and 12th), in nearby Parli, was no different. The students sat on the ground under tin or metal roof shades for classrooms without benches. In the meantime, he became conscious about the lack of quality education, drinking water, access to good food, and transportation, and like many other children in his village struggled against the odds of rural life. He moved on to pursue an engineering degree much reluctantly and completed his graduation in 2005.

The two things that motivated Santosh, were his desire to provide a better life and do something good for the community. “Since my childhood, and college days, I actively participated in social functions, activities and knew somewhere that I had to give back to society”, he said.

Career Crunches

Santosh arrived in Mumbai in 2005, soon after his graduation for career opportunities. He began his career as a door-to-door salesperson selling mobile handsets between Churchgate and suburban Mira Road. He was not interested in engineering-led jobs and opted for the one that enabled him to interact with people. “My passion lies in understanding problems, imparting solutions, networking, and communication, and I did not enjoy a desk-bound job,“ he said. The selling job led to his next move as a Sales Executive with HBL Global Pvt Ltd, a subsidiary of HDFC Bank, selling business loans, and personal loans. He pursued the job for two years and networked with people from diverse fields, including directors, CEOs, CFOs, and celebrities.

“Although it was a challenging job, I enjoyed knowing my clients, learning from them, and their life experiences,” said Santosh.

He was challenged initially to match the communication skills of his colleagues and to cope with soft skills and language efficiency. “Most colleagues had good schooling, knew good English, with superior technical and soft skills and communication techniques, which deterred me from actively participating in group discussions. I always sat at the back, making sure that my seniors did not question me, fearing that I would not be able to respond to them in English,” he said.

"We are still working with our very first school and have enhanced the Study Mall facility and added other facilities, including digital classrooms. We forge a relationship with the schools and continue to hand-hold them for future progress

English Vinglish

My repertoire of the English language was primarily ‘Sorry’ and ‘Thank You’. It was difficult for me to place an order at McDonald’s because I did not know how to respond in English, preventing me from buying a burger even though I could afford it,” said Santosh. “This was the case throughout my corporate journey between 2005-2017,” he added.

He often got corrected by his colleagues on his strong Marathwada Marathi accent, which flipped into his English communication. He took it all in his stride and gradually filled in the learning gaps. “It was a struggle, but I enjoyed my job and kept learning from peers and seniors. I then took a job break and pursued MBA”, he said. His association with the Rizvi Institute of Management Studies and Research, Mumbai, finally fulfilled Santosh’s long-term desire for quality education. “I aimed to learn better communication and soft skills and desired an equal opportunity to study in a good college. I desired an atmosphere where I could access a computer, a library, good learning facilities, and develop friends from different backgrounds,” said Santosh.

Germinating an Idea

Santosh laid the foundation of ThinkSharp, as a Web portal, ThinkSharp.in, during his MBA days (2009-2010). It showcased the success stories of individuals he had connected with, during his two years at HBL Global. “I thought of conducting interviews and publishing individual success stories for MBA aspirants and other audiences,” said Santosh. He managed the website for a year, which unfortunately had to be shut down, due to a lack of proper operational or revenue-generating strategy. “I was constrained by my communication skills and when my co-founder quit, I had no recourse but to shut down the portal,” he said.

Post his MBA, Santosh re-entered the corporate sector as a Sales Manager with Reliance Capital in 2009-2010, which was a turning point in his career. During the phase (2010-2017), he became Area Sales Manager with Magma Fincorp Ltd, moved to Edelweiss Financial Services Limited, and switched shops as Territory Sales Manager with Tata Capital. His second innings with the corporate sector took him a notch higher as he managed financing deals worth over Rs 50 to Rs 100 crores, involving individuals and top businesses, and corporate houses. “I started believing in my capabilities while meeting high net worth individuals and corporates, and decided to rewire my entrepreneurial journey,” said Santosh.

A Non-profit Path

Santosh gradually realised that making money was not his prime motive and redesigned the ThinkSharp concept as a not- for-profit organisation. In 2010-2011, social entrepreneurship was gaining mileage. Santosh invested time in learning about established social enterprises, the likes of Goonj and Akanksha, and was inspired by Professor Mohamed Yunus, the Nobel Peace Prize winner Bangladeshi social entrepreneur, banker, and economist. “I had no clarity then, but was sure about contributing to the education sector,” said Santosh.

He shuffled through ideas on whether to start an institute or feed children, and the plethora of social improvement ideas. However, his 25 years of rural roots nudged him to do something in the education sector. “So, tomorrow if children from villages like mine come to Mumbai, they will be a much-improved version of me, in terms of communication and skills required in a competitive world, ” he said.

The Study Mall

After much brainstorming, he decided on an after-school center as his pilot project. They reviewed the overall child development needs and enabled access to various books, including story and poem books, computer access, and indoor games. Santosh hired a center coordinator from the village, who supervised the children’s homework, taught computer skills, and kept the students engaged in activities. He coined a name for the generic center as a ‘Study Mall’, akin to a shopping mall, where children receive all educational resources, reading and learning materials, and other creative pursuits under one roof.

They launched the first after-school Study Mall in 2013 in Surangali, Jalna district. Santosh’s friend Bhagwan Jadhav, hailing from the Marathwada region, shared Santosh’s passion for building education equity across state schools. Bhagwan was a key founding member who offered the place and Santosh’s wife, Dr. Shraddha Bhange, too became a ThinkSharp founding member. They mobilised angel funding and private donations from Santosh’s colleagues at Reliance Capital, friends, his wife, and other personal investments. They collected around Rs 1 lakh in small tranches of Rs 10,000, Rs 5000, and even smaller contributions and started the Study Mall center in October 2013 with two basic refurbished computers and a few books, using donated mats for the flooring. It is now providing access to digital learning tools, computer education, reliable solar power, and various other educational resources under one roof.

The Study Malls resulted in around 30 per cent increase in school attendance, enhanced the children’s attention span, and increased study time by 300 per cent. There has been a 30- 40 per cent jump in literacy skills and a 5-10 per cent increase in academic scores. With teachers accessing new teaching tools and resources via the Study Malls, children have been able to enhance their knowledge, and academic development, opening new career options and developing personal growth.

"Children who are unable to afford quality education in private schools, depend on government-run schools. We aim to reach out to these children, irrespective of their backgrounds

The Second Trajectory

With the pilot project off the ground, Santosh parallelly continued with his corporate commitments. He had contemplated quitting his full-time job, but the requirement for a steady income prevented him from doing so, until December 2017, which triggered important changes to his plans. Dr. Bhange, Santosh’s spouse, landed a career opportunity in Paris, and the couple shifted base, enabling Santosh to quit corporate life forever. “While it was a good opportunity for my wife, I looked at improving ThinkSharp’s network and both went to Paris,” he said.

He networked in Paris, conducted sessions, attended conferences and meetings, and connected with several HNIs (high net-worth individuals). Meanwhile, the Indian chapter required significant impetus, and during their year-long stint in Paris, Santosh travelled back and forth, especially after ThinkSharp bagged their first corporate funding, dividing his time between India and Paris. ONGC became their first corporate sponsor, followed by Newfold Digital company and Young Volunteer Organisation (YVO), a non-profit. The projects gained momentum and realising Osmanabad, Latur, Beed, and the Konkan region became easier,” said Santosh.

The move proved fruitful as the foundation gained multiple sponsors, including a few corporates who became their lifelong CSR partners. “I never had to look back. From that one Study Mall in Surangali village in 2013, we developed our centers gradually, but with a little re-invention of our pilot mall concept”, he said.

Tweaking the Model

The first after-school Study Mall largely depended on ambassadors introducing local resources and goodwill of the panchayat and other government connections, including friends and families as volunteers, which posed specific problems. “With the after-school concept, we incurred recurring costs and had to pay rentals for the premises, and the coordinator’s salary. We faced local parochial issues, disallowing a few kids to mingle with others, which defeated the purpose of equal opportunity”, said Santosh.

In 2015, Santosh’s experience with the Surangali model paved the way for exploring the Study Mall concept within existing government schools. They believed in universal quality education and considered safety and security measures while introducing the same concept within school premises. They worked continuously with Zilla Parishad schools across Maharashtra, and established their second in-school Study Mall in 2015 in Vangani, off the Kalyan-Dombivli belt with support from the NGO YVO, one of their permanent partners. “Children who are unable to afford quality education in private schools, depend on government-run schools. We aim to reach out to these children, irrespective of their backgrounds”, said Santosh. They have enabled over 200 Study Malls across Maharashtra while discontinuing their earlier after-school Study Mall model in 2018.

With the gradual success of their centers, surrounding village schools approached them for assistance, and suddenly they had some 100+ applications to sift through. Realising that they were now on the right track, Santosh decided to build selection parameters and develop better management, implementation, and monitoring mechanisms, adopting technology like a set of 20 Google form questionnaires to scrutinise the applications. It helped gauge the basic infrastructure needs, conduct a physical assessment of schools, and on-site visits to ascertain the current conditions and understand the seriousness of the teachers in running the projects and handling the sponsorship funds and facilities appropriately.

"We have devised programmes, equipment and funding, to run on solar power. We are thriving to provide the school children with good ventilation, fan, and lights so that they no longer have to sit in dark classrooms or face learning lag due to power shortages

“It is equally important to understand the level of engagement, and involvement of the gram panchayat in the school’s educational activities, as they are mandated to spend 20% of their budget on education. We, therefore, have to check with the Sarpanch on the education spend and other requirements across the individual government schools”, said Santosh. Their model is to keep long-term associations with all the schools. “We are still working with our very first school and have enhanced the Study Mall facility and added other facilities, including digital classrooms. We forge a relationship with the schools and continue to hand-hold them for future progress,” said Santosh.

Currently, their organisation operates with 12 full-time paid employees, including Santosh, and innumerable unpaid volunteers and consultants. The core model works on the fellowship pattern, wherein 10 fellows on the company’s payroll are trained in relevant skills, primarily tech deployments for running the Study Mall programmes. “The idea is to build the Fellows as future leaders and grow the team. They monitor, maintain and report daily to the management on various project implementations across government schools”, said Santosh.

Building Digital Mileages

The pandemic proved a boon for enabling digital growth in the lives of the students in the hinterlands. As people understood the importance of technology to remain connected, Santosh received help from school students in urban zones and cities, who donated laptops and tablets to the village kids. “Many corporate volunteers engaged with our students, along with their local teachers, investing 4-5 hours across multiple online sessions with different groups,” said Santosh.

As students could not attend classes physically, they had to overcome the non- availability of books. It laid the foundation of ThinkSharp’s customised Digi Library, where the kids accessed reading material digitally. “It is a full-fledged android-based digital library with approximately 1000 pdf books, 400 audio-video books and can be accessed by all,” he said. During the pandemic, they enabled home-schooling, the Digi Library concept, and mobilised the Vidyarath, a converted truck equipped with a library, science, and computer learning programs, and sent it to different communities around Pune during Covid times. We would engage the children in groups, maintaining social distancing,” he said. The Vidyarath continues to run, visiting one school each day, with plans to buy another truck and reach out to distant schools in Maharashtra.

As computer education is the backbone of most of their programmes, they had to resolve issues of power outages in the village schools. “We have devised programmes, equipment and funding, to run on solar power. We are thriving to provide the school children with good ventilation, fan, and lights so that they no longer have to sit in dark classrooms or face learning lag due to power shortages,” said Santosh.

Engaging Corporates

Santosh’s continuous association with corporates enables him to align with their CSR requirements. He has classified his sponsors as those who support schools near their factories or offices and those who support quality work across any school. Most companies with factories around Taloja, MIDC, Palghar, or Vapi, prefer good control of the projects, enabling them to visit the schools, which helps them to budget their CSR kitty. “While the state government’s total CSR budget is around Rs 2300 crore (last fiscal), around Rs 1500- 1700 crore is disbursed across Pune, Mumbai, Nashik, while the hinterlands of Vidarbha and Marathwada receive a meager Rs 1 crore to 3 crores, causing a huge gap in CSR outreach programmes. We, therefore, try to convince companies to support and engage more with far-flung schools in Maharashtra,” said Santosh. Santosh estimates that 60 per cent of assistance is from the service sector while 40 per cent is from manufacturing units.

“Manufacturing companies prefer to support their local community schools, as most of their labour force belongs to these communities. We get a free hand to mobilise funds from the IT or service-related companies as they like to work with a good proposal, irrespective of the locations, ensuring that the project is in good hands,” he said.

ONGC, Tata DLT, Newfold Digital, and YVO have become their constant partner, with several other companies joining along the way for various projects either ad-hoc or via holistic engagements. “We share our stories, surveys, reports, photographs, videos, and our on-field experiences, encouraging their employees to engage via different voluntary activities either onsite or virtually,” he said. ONGC has been engaging with ThinkSharp since 2018 and in their most recent third phase of engagements, they have helped set up 34 digital classrooms across Maharashtra’s coastal belt impacting schools along Shrivardhan (Raigad district), Murud-Jangira, Mud Island, Vasai-Virar and Dahanu-Palghar belts in the current fiscal, reaching a total of 54 e-learning classrooms in the past three years. YVO and Polycab have jointly enabled 20 schools in the current fiscal.

“Dell Technology offers pro-bono services by building a technology solution for our kids. Their technical experts work closely by designing a product or service”, he said. Google has been supporting the foundation for the past 7-8 years and promoting ThinkSharp pop-ads on Google search engines, without charging them. Microsoft has enabled free licensed MS products for Santosh’s team, but the schools run on paid versions/license copies

IT and service sector companies often set up their digital learning classrooms, and computer education programmes, and enable the digital library scope. “Many of the companies prefer to run multiple programmes in the same school rather than go to multiple schools,” said Santosh. Others with a big budget even opt to take care of school repairs and construction, as spending money is a risk across dilapidated school buildings, defeating the purpose of quality infrastructure.

"Manufacturing companies prefer to support their local community schools, as most of their labour force belongs to these communities. We get a free hand to mobilise funds from the IT or service-related companies as they like to work with a good proposal, irrespective of the locations, ensuring that the project is in good hands

Matching Financial Modes

While engaging with corporates is one way of strengthening money flow for projects, Santosh’s team has 2-3 different ways to scale and sustain their projects long-term. “Corporates are willing to pay you good admin fees, ranging from 5 % to 15%, which covers our admin expenses”, said Santosh. Their relationship with corporate partners often starts with assisting with one library, leading to infrastructure facilities and in some cases adding construction enhancements to school buildings. “Our relationship has been evolving year-on-year, adding to the projects’ sustainability,” said Santosh.

However, he acknowledges the support from individuals and philanthropists who are important for sustaining their projects consistently. “The individuals and philanthropists keep the kitty floating, even when corporates back off, like during the pandemic when they did not have a CSR budget. The individual contributors donated anywhere between Rs 10,000 to Rs 1 lakh. We have about 50 people who donate monthly and keep us afloat”, he said.

Crowdfunding is another means to garner funds domestically. While they accept similar contributions from Indian nationals living abroad, a lack of an Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010 (FCRA) registration does not legally permit them to accept foreign donations. “It requires a lot of compliance and a dedicated person to oversee the FCRA process. We are currently ready for some international funds and plan to apply for the FCRA license,” he said.

They have targeted developing around 500-1000 schools including the current ones and would continue reaching out to these schools. “There is a lot more scope in working with the same schools and building life-long relationships,” he said.

Between Passion and Cult

With the current frenzy for social entrepreneurship, Santosh believes that it should come from the heart, and not merely by training in institutions. He acknowledges the various social entrepreneurship degrees that have cropped up lately and feels, he might have benefitted from them too in the initial stages. “While it is good to have certified social entrepreneurs working with a good set of skills and knowledge, my advice is that you learn, adopt and implement those skills with a long-term vision. It should never be an escape route from the corporate world or for overcoming boredom or personal incompetencies”, said Santosh.