Victory of Man over Mountain

"If you are faced with a mountain, you have several options. You can climb it and cross to the other side. You can go around it. You can dig under it. You can fly over it. You can blow it up. You can ignore it and pretend it’s not there. You can turn around and go back the way you came. Or you can stay on the mountain and make it your home."

- Vera Nazarian,

The Perpetual Calendar of Inspiration

Life is always full of problems. Most of us keep on complaining, blaming and criticising others. Some people continuously think and analyse how these problems can be solved either by themselves or by the authorities concerned. This is the story of a man who did not think, but acted. He was among the poorest of India’s poor. He decided that if those in power would not help his people, he would.

This is the story of Dashrath Manjhi: the man who moved a mountain so that his people could reach a doctor in time. It was 1960; landless labourers, the Musahars, lived amid rocky terrain in the remote Atri block of Gaya, Bihar, in northern India. In the hamlet of Gehlour, they were regarded as the lowest in a caste-ridden society and denied basic necessities: water supply, electricity, education and healthcare. A 300-foot tall mountain loomed between them and civilisation in the adjoining Wazirganj. Like all the Musahar men, Manjhi worked on the other side of the mountain. At noon, his wife Phaguni would bring his lunch. As they had no road, the trek took hours over the mountain. Manjhi tilled fields for a landlord; he would also quarry stone, and in a few hours, he would be tired and hungry. Manjhi would watch and wait for phaguni. That day, she came to him empty-handed, injured. As the harsh sun beat down, Phaguni tripped on loose rock; her water pot shattered. She slid down several feet, injuring her leg. Hours past noon, she limped to her husband. Manjhi rushed to chastise her for being late, but on seeing her tears he became emotional.

He made a decision of a lifetime: he would make a path through the mountain. Having made up his mind to challenge the mountain, Manjhi sold his goats to buy a hammer, a chisel and a crowbar. He climbed to the top and started chipping away at the peak of the mountain. Years later, he would recount, “That mountain had shattered so many pots; claimed lives. I could not bear that it hurt my wife. If it took all my life now, I would carve a road through the mountain.” In a few days, a word about Manjhi’s unusual adventure had spread. The work was so arduous that it left him with no energy to earn his livelihood. He had no option but to quit his job. His family often went without food. Then, Phaguni fell ill. The doctor was in Wazirganj, 75 kilometres over the mountain. In the absence of any approach road, it was not possible for Manjhi to take his wife to the doctor. The inevitable happened-Phaguni died. Her death only spurred him on further. It was not easy. Unyielding, the mountain would cascade rocks at him. Hurt, he would rest and start again. At times, he helped people carry their things over the mountain for a small fee—money to feed his children. After 10 years, as Manjhi chipped away, people saw a cleft in the mountain; some came to help.

"I do not care for these awards, this fame, the money. All I want is a road, a school and a hospital for our people. They toil so hard. It will help their women and children. That mountain had shattered so many pots; claimed lives. I could not bear that it hurt my wife. If it took all my life now, I would carve a road through the mountain"

- Dashrath Manjhi

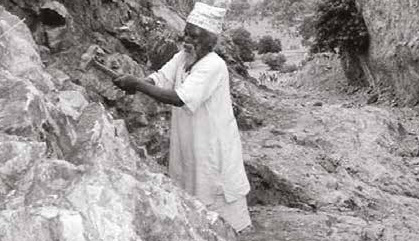

Dashrath Manjhi making a path through the mountain

Dashrath Manjhi making a path through the mountain

At the end of an effort lasting 22 years, Dashrath Das Manjhi, the outcast landless labourer had finally conquered the mountain: he had carved out a road 360 feet long, 30 feet wide. Wazirganj, with its doctors, jobs and school, was now only five kilometres away. People from 60 villages in Atri could use his road. Children had to walk only three kilometres to reach school. Grateful, they began to call him ‘Baba’, the revered man. But, Manjhi did not stop there. He began knocking on doors, asking for the road to be tarred and connected to the main road. He walked along the railway line all the way to New Delhi, collecting signatures of stationmasters in a book. He submitted a petition for his road, a hospital for his people, a school and water. In July 2006, ‘Baba’ went to the then Bihar Chief Minister (CM) Nitish Kumar’s ‘Junta Durbar’. The CM overwhelmed, got up and offered ‘Baba’ his chair, his minister’s seat; a rare honour for a man of Manjhi’s stature.

The Government rewarded his efforts with a plot of land. Manjhi, in turn, donated the land back for a hospital. They also nominated him for the ‘Padma Shree’, but forest ministry officials fought the nomination, calling his work illegal. “I do not care for these awards, this fame, the money,” he said. “All I want is a road, a school and a hospital for our people. They toil so hard. It will help their women and children.” He had carved out a road 360 feet long, 30 feet wide. It would take the Government 30 years more to tar the road. On 17 August 2007, Dashrath Manjhi, the man who moved a mountain, lost his battle with cancer. All that he had done was for no personal gain. “I started this work out of love for my wife, but continued it for my people. Had I not started it, no one would have.” Manjhi’s words reflect the reality of our country.

Manjhi’s legacy and his inspiration live on-it lives on among the thousands of Indians who are making a difference to their fellowmen, fighting new battles and overcoming challenges. It lives on in so many of you who are moving your own mountains. I salute the spirit of Dashrath Manjhi, which drove him to conquer a mountain.