Tracing the trajectory of the Global Merchants – The Sassoons

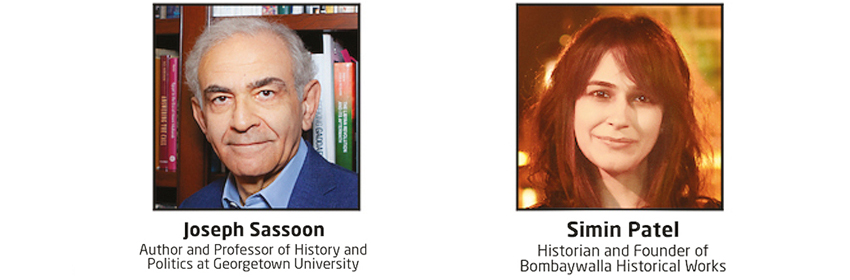

Known as the ‘Rothschilds of the East’, David Sassoon and his heirs established a trading dynasty along the Silk Route, and expanded into real estate, banking, and innumerable other commodities which then formed the foundation of globalisation today. The influence of the Sassoon family continues to shape economies, innovations and even politics of some global capitals. The lecture demonstration on Sassoons: The Global Merchants, presented by the Bangalore Literature Festival, Bombaywalla Historical Works, Penguin Random House India, and Avid Learning, offered a closer look at one of the remarkable business dynasties of the nineteenth century with Joseph Sassoon, author and professor of History and Politics at the Georgetown University

Joseph Sassoon, a descendent of the famous Sassoon family, draws instances from his recent book, ‘The Global Merchants: The Enterprise and Extravagance of the Sassoon Dynasty’, to give fresh perspectives on how these influential merchants of the 19th and early 20th centuries shaped cities like Bombay, Pune, Shanghai, London, and their contribution to prosper it economically, politically, socially and towards its arts, culture and architectural legacies.

"The Sassoons, a Baghdadi Jewish family, built a global trading enterprise by taking advantage of major historical developments during the 19th century. Their story presents an extraordinary vista into the world in which they lived and prospered economically, politically and socially"

Excerpts from Joseph Sassoon talk...

Joseph Sassoon

Joseph Sassoon

The Sassoons, a Baghdadi Jewish family, built a global trading enterprise by taking advantage of major historical developments during the 19th century. Their story is not just one of an Arab family that settled in India, traded in China, and aspired to be British; it also presents an extraordinary vista into the world in which they lived and prospered economically, politically and socially. Jews had been present in Mesopotamia for some 2500 years since the first exile in 6 BC following the conquest of Judea by the Babylonians. There were thriving Jewish communities in the cities in the province of what is now called Iraq, and there were likely more Jews there than there were anywhere else in the Arab east.

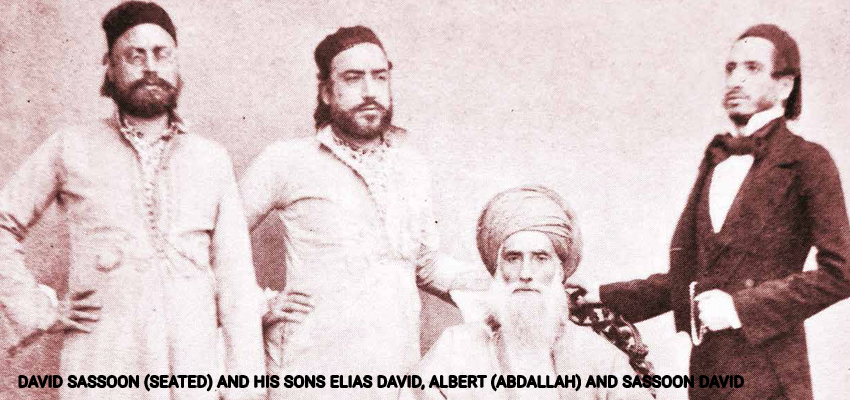

For many years, the father of David Sassoon, the dynasty’s founder, Sheikh Saleh Bin Sassoon, was appointed by the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire as the chief treasurer of the province of Baghdad. But a corrupt governor in the 1820s poisoned the relationship. The Sheikh and his son David, and David’s family, fled to Bushire in southern Iran. In Bushire, David learned about India in general and about the city Bombay in particular. The city was the destination of so much of the trade passing through Bushire. David could have opted for Isfahan-Persia’s largest trading centre, or followed other Baghdadi Jews to Bahrain and other Gulf countries to take advantage of the flow of goods between the Gulf and India. But memories of the family’s suffering were fresh and the relative security offered by the British rule attracted and the decision was made: The Sassoon would cross the Arabian Sea and begin a new life in India. With the demise of his father, it was only David and his young family who made the hazardous journey to Bombay.

When he arrived in Bombay in the early 1830s, its inhabitants numbered no more than 200,000 but were very diverse: Hindus, Muslims, Parsis, Armenians, Portuguese, and Jews. There was a Jewish connection with the city from the 16th century; by the early 1830s there were approximately 20-30 families out of a Jewish population of 2500 and these families called themselves ‘Jewish merchants of Arabia-inhabitants and residents in Bombay’.

David strived to familiarise himself with the merchants and the commodities they traded in, in Bombay. He began learning Hindustani as soon as he arrived, adding it to his fluency in Arabic, Hebrew, Turkish and Persian. He spent his day by the cotton exchange, talking to traders and agents, scrutinising the international news for anything that might send prices up or down, and making contact with his old acquaintances in Baghdad and the Persian Gulf.

He instilled in the family that you can lose money and remake it many times but the reputation you can lose only once. Not long after his arrival, David started exporting textiles on a small scale to merchants in the Ottoman Empire. After the Opium Wars ended in the 1840s, he began trading opium but he was a small player. His elevation into the first rank of businessmen in Bombay was gradual. There was no single event or trade that dramatically changed the state of affairs. He just continued developing his network of traders and exploiting opportunities when they arose. Jeejeboy wrote once that David’s success was because he had 14 children spread around the world.

The sons were trained in business from their youth and were later sent to different locations such as Baghdad and the Gulf port to meet other traders, gain experience, and learn Arabic. Once in Bombay, David realised that the fate and success of the family had to be tied to the British empire, and the firm of David Sassoon & Sons began a long connection serving British colonial economic and political interests wherever they had branched out. Bombay was conducive to the life of minorities like the Jews and welcomed them in different aspects. He was granted British citizenship in recognition of his services. Twenty years after his arrival in Bombay, he swore the oath of allegiance to the British and he still hadn’t learnt enough English to sign his own name-it was signed in Hebrew.

The Sassoons felt they were part of India and Bombay and realised that their new home afforded them safety and security. They considered it home until the third and fourth generations which became anglicised. They purchased a grand house in Bombay, Sans Souci, where many big events took place. Today, it is the Masina Hospital, which still contains the court of arms of the family on the second floor.

Abdullah, the oldest son, 1872 moved to England and became Sir Albert. The second son Elias really opened China; soon as the Opium War ended he was shipped at a very young age to Hong Kong and other parts, where he started exploring business. When David Sassoon died in 1864, the two sons had gone into conflict, and split resulting in two competing firms. (Abdullah’s granddaughter) Farha Sassoon, a phenomenal personality, I see not just as the first woman CEO in India but as a global CEO managing the day-to-day activities. And finally, there is Victor Sassoon, the grandson of Elias, who bet on China and lost when the country nationalised all the family’s assets.

In the field of philanthropy, the founder David and his son Abdullah initiated an innovative method-they taxed every trade they did a quarter of a per cent, irrelevant of whether the trade was profitable or not. As they were involved in hundreds of trades, at the end of the year, a very large amount would be accumulated. They built the David Sassoon Library in Bombay, the Sassoon Hospital in Pune, and other such institutions.

Regarding their global reach, the Sassoons spread to port cities because of trading. For example in China, they exported opium and imported silk and tea, they also traded rice, pearls, and other commodities. The three biggest hubs were Bombay, Shanghai and London.

The second half of the book examines how this dynasty lost this incredible almost-empire in such a short time in the 20th century. It’s not just economically but about culture, assimilation with Britain and Anglicisation, and it becomes an ideology much more than a business or a tradition.

Joseph Sassoon also conversed with the Historian and Founder of Bombaywalla Historical Works, Simin Patel on the contributions, influences and affluence of prominent members of the family and their contribution to forming Bombay as a modern port city.

"The Sassoons spread to port cities because of trading. For example in China, they exported opium and imported silk and tea, they also traded rice, pearls, and other commodities"

Excerpts from the interaction...

Simin Patel: Tell us about Farha who became Flora, and ran the business from Bombay.

Joseph Sassoon: Her husband had died and when she expressed the wish to run the business, it was a shock to the family, to the mercantile group in India, but they really didn’t have any choice as none of them were willing to go back to Bombay or Shanghai to run the business. Once she got into it, and the more successful she was, the more they conspired against her. It really bothered them that she was so successful. When a representative from the American Congress was coming to India to make a study of cotton and textile, he conveyed that it’s enough just to talk to Farha... this goes out into American newspapers and upsets the family even more.

Patel: Farha also makes peace between the two giant firms-David Sassoon and E D Sassoon

She realises that once Abdullah dies-and Elias has died much earlier-that this is such a stupid thing that they are facing the same issues relating to cotton and textile, and the opium which was facing a lot of opposition. They sat on the boards of the same banks, such as HSBC and the banks in India. And after their demise, she put them back together, so to speak. When she eventually left for England, she was garlanded and it bore the inscription ‘Her Majesty The Queen of Bombay and the Empress of Malabar Hill’!

Patel: Their contribution to the textile trade.

The trade was actually more developed by the ED Sassoon than David Sassoon. Once Flora was out of action, there wasn’t any proper leadership. It’s interesting that at some point the combination of mills between the two companies is the largest component in the whole country. There were 34–36 mills and each one was profitable. Then comes World War I and they become very profitable, but then problems developed and they start going down. They were stuck, wanting to get out but not knowing which business to go to. They lacked the leadership from 1900 onwards. Victor decided to focus on real estate which, to some extent, was a good bet but he didn’t figure out that China was going to change - he misread that in a big way.

Patel: The Sassoons today.

They are spread around the world. Some of them know about the old glory, others have just heard about it. When I was in London, I met with some Sassoons that I hadn’t met before. Like with all families, it’s not a perfect family.

About the book

The Global Merchants: The Enterprise and Extravagance of the Sassoon Dynasty.

The Sassoons were eminent traders, one of the great business dynasties of the nineteenth century. The book by Joseph Sassoon reveals the secrets behind the family’s phenomenal success, tracing how a handful of Jewish exiles from Ottoman Baghdad forged a mercantile juggernaut from their new home in colonial Bombay. It revisits the vast network of agents, informants and politicians they built, and the way they came to bridge East and West, culturally as well as commercially. As one competitor remarked, ‘silver and gold, silks, gums and spices, opium and cotton, wool and wheat - whatever moves over sea or land feels the hand or bears the mark of Sassoon & Co.’ Drawing for the first time on the vast family archives, Joseph Sassoon brings vividly to life a succession of remarkable characters. From a single generation: Flora, the first woman to steer a major global business, Siegfried, the poet, and Victor, the tycoon who drew the stars of Hollywood’s silent era to his skyscraper in Shanghai. Through the lives these ambitious figures built for themselves in London, Bombay and beyond, the book draws the reader drawn into a captivating world of politics and power, innovation and intrigue, high society and empire. While The Global Merchants is an intimate portrait of a single family, it is also a panorama of the 130 years of their prominence: from the Opium Wars and opening of China to the American Civil War, the establishment of the British Raj to India’s independence. These combine to give a fresh perspective on the evolution of one of the defining forces of their age and the present: globalisation. The Sassoons were variously its agents, advocates and casualties, and watching them moving through the world, we perceive the making of our own.