Discovering the Conjuror’s trick

‘The Conjuror’s Trick: An Interpretive History of Paper Money in India’ looks at the socio-cultural legacy of paper money in India and discusses the era of free banking. A must-read for anyone interested not just in the trajectory of the nation’s relationship with paper currency but also the evolution of its design, nature and value

Hundis were the predecessors of paper currency

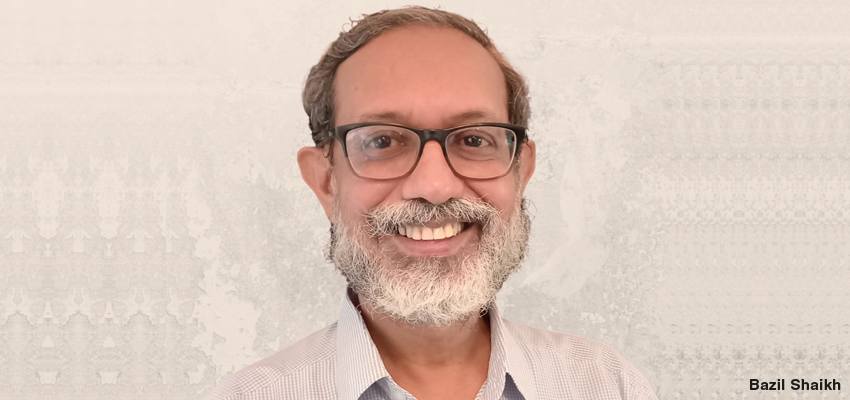

Popular since medieval times, these hundis-promissory notes-were slightly different from banknotes. “For starters,” says Bazil Shaikh, former central banker and author of the newly released ‘The Conjuror’s Trick An Interpretive History of Paper Money in India’, “these paper documents were not designed to circulate amongst the public and were used by a closed community of Indian bankers, merchants, governments for trade and financial transactions such as borrowing and lending and were as such, transferrable only within that closed circuit of bankers, merchants and others initiated in methods of finance.”

This is vastly different from modern-day notes as we understand them. Precisely why Shaikh’s recent work is a fascinating read: it gives us invaluable nuggets on the history and evolution of paper money and banking in India.

The book, says Shaikh, has its origins in the work done to set up a monetary museum for the Reserve Bank of India in 2004. Paper money was a part of the Museum storyline. “While there has been some excellent and pathbreaking documentation of Indian notes, notably by P. L. Gupta and Rezwan Razack and Kishore Jhunjhunwala, these are from a notaphily perspective. There was the need for a narrative which placed the evolution of paper money in a socio-economic and historical perspective,” he says. After all, few instruments showcase the priorities of a developing country as do its notes.

The book explores…

The socio-cultural history of paper money in India, tracing its journey from the 1770s to the present. As mentioned earlier, a fascinating part of the story of paper money in India was its vast and rich experience with ‘free banking’ when private banks issued banknotes that circulated as money. However, while ‘free banking’ has been elaborately documented in a host of countries, there is virtually no mention of the Indian experience. “Unto that end, this book is amongst the first to explore and document the Indian free banking experience as a part of the story of India’s tryst with paper money,” says Shaikh.

So what exactly is free banking?

“The system whereby lightly regulated banks are free to issue notes that are convertible into coins and circulated as money without a lender of last resort is known as free banking,” explains Shaikh. “In India, such a period extended between 1770 and 1861 when the Paper Currency Act prohibited banks from issuing banknotes payable on demand and vested the monopoly of note issue with the Government of India.”

The first comprehensive volume that looks at the socio-cultural legacy of paper money in India. In the late 18th century, there were few restrictions on the setting up of banks in India. Such banks typically issued banknotes that circulated as money. For instance, in the 1820s, notes of the Bank of Hindostan, Bank of Bengal, The Commercial Bank, the Calcutta Bank competed with each other for circulation in Bengal. To the extent the notes issued exceeded the reserves held by the bank, the banks were in a position to create money out of thin air-much like a conjuror would.

Assorted episodes from history add to the flavour of the book

“The idea of a bank as a repository of money has traditionally fired the imagination of bandits and robbers-be they crusty villains or suave fraudsters,” smiles Shaikh. “Newspapers reported a case in 1795 where plans of a formidable gang of robbers planning an attack on the Bank of Hindostan were thwarted. Interestingly, the gang consisted of English, Portuguese, Italian and other foreigners!”

As things stand, currencies today are no longer linked to gold or silver or any other precious metal. They were finally delinked from gold after the breakdown of the Bretton Woods System in 1971 when US President Richard Nixon severed the link between the dollar and gold.

While paper money remains an essential part of daily life, its worth is tied not to its intrinsic value but rather to a shared system of belief, trust and knowledge.

"Paper currency, when it was first introduced, constituted a disruption-it introduced the idea that money could be a token rather than a metallic coin"

- Bazil Shaikh

Insights into the life of a nation through notes

It is a detailed look at note design and changing symbolism and insights into the life of a nation through notes: colonisation, war, independence, partition, green revolution and industrial developments, satellite launches, demonetisations.

Early banknotes sought to portray trade and commerce along with colonial motifs. British India notes had the King’s portrait. Notes of independent India have our National Emblem- The Lion Capital on the Ashoka Pillar at Sarnath. The Brihadishwara Temple at Tanjore (Thanjavur) was imprinted on the Rs.1000 note while the Gateway of India was the vignette on the Rs.5,000 note.

Over time, the fauna vignettes appearing on notes in the colonial era were gradually replaced by the symbols of development and progress. The Hirakud Dam, described as one of the ‘temples of modern India’ replaced the elephant on the Rs.100 note; a farmer driving a tractor celebrating the Green Revolution-replaced the deer on the Rs.5 note; the Indian satellite Aryabhatta, which marked India’s debut in space, replaced the tiger; the Parliament House on the Rs.50 note sought to affirm India’s commitment to democratic values. The motifs on later notes made a marked change to Indian art forms and were more free-flowing, giving a more informal touch to the notes.

The Mahatma Gandhi Series sought to reaffirm our commitment to Gandhian values and the latest series of notes highlight India’s cultural and historic diversity besides making a note of India’s achievements in science and space technology.

Nuggets on the changing appearance and design of banknotes

“Early banknotes were issued in a standard format. They promised to pay the stated sum in current coin to the person to whom the note was issued or to bearer,” shares Shaikh. “They typically had a serial number, the date of issue and two or sometimes more signatures of the Accountant as well as of the Secretary who represented the bank. The notes could be transferred by endorsement and delivery, the chain of endorsements creating an audit trail. “Over time, as the circulation of banknotes increased, the practice of endorsement was discontinued and notes transferred from person to person merely by delivery; subsequently, notes were made payable to merely to bearer the way they are today. By the 1820s, notes were being printed on both sides. Some early notes up to the 1820s were also issued in denominations such as Rs.4, Rs.8 and Rs.16 based on the Indian binary system. The present visual format of banknotes with a clear window watermark was largely set in the mid-1920s when pictorial notes of George V were issued.” While the visual format as remained largely unchanged, the overt and covert security features embedded in the substrate (paper) as well as in the printing have been very substantially enhanced over time to prevent forgeries,” he says.

Experiments in alternative systems of transactions (Labour notes, Time banks, Gosaba experiment, Khadi hundis, Cryptocurrencies) and interesting anecdotes on Money and Erotica, Shipwrecks and Forgeries.

Demystifying money: The book explores the transition from metallic to fiat money, the system of central banking and the changing principles of note issue.

The work also sheds light on important milestones or their delay

For instance, it took nearly half a century to universalise currency notes in India. “Government Paper Currency was introduced in the aftermath of the Great Uprising of 1857 when conditions were unsettled and there was unease with the colonial government. As the British Empire consolidated its hold as the supreme power and established stability, confidence in the currency grew. Confidence amongst the public to hold notes eased the compulsions for ‘absolute, instant and never failing convertibility’. Notes were universalised in a calibrated manner commencing with the then lowest denomination note of Rs.5 in 1903 and gradually extended to higher denominations. Universalisation meant that notes were convertible anywhere in India, unrestricted by the circle where they were issued. With universalisation, currency circles became redundant,” explains Shaikh.

Reimagining money in the digital format: the paradigm shift

The book becomes all the more relevant given the power politics of our times. “Paper currency, when it was first introduced, constituted a disruption- it introduced the idea that money could be a token rather than a metallic coin. Once again, today, a major disruption is taking place where money is being reimagined in the digital format,” elaborates Shaikh. “Power shifts are taking place between the state, corporates, communities and individuals. These have influenced money. Local complementary currencies are one end of the spectrum and cryptocurrencies that recognise no borders are the other end of the spectrum. Central banks, on their part, are responding by seeking to introduce Central Bank Digital Currencies. “These developments hold promise as well as invoke concerns for the economic organisation of society, surveillance and freedom. We live in interesting times,” he rounds off.

A scholarly yet lucid read, the book is a musthave for students of economics, corporate careerists, bankers and anyone interested in the economic evolution and timeline of India. The production value is top-notch, the vignettes of assorted notes make the subject come alive. The Conjuror’s Trick An Interpretive History of Paper Money in India is brought out by Marg @ Rs.1800.

About the author

Bazil Shaikh, author and former central banker, has worked in areas spanning trade, exchange rate management, rural development and governance, amongst others. He headed the team which conceived, researched and curated the RBI Monetary Museum, Mumbai. His other publications include ‘The Paper and the Promise’ and ‘Mint Road Milestones: RBI at 75’.