Batting for an Equal Society

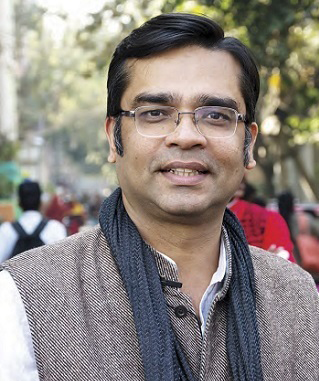

A global civil society leader and one of the leading experts of people-centric advocacy, Amitabh Behar, CEO, Oxfam India, is an authority in tackling economic and gender inequality and building citizen participation. Behar has an M. Phil in Political Science from Jawaharlal Nehru University. He was also a research fellow at the University Grants Commission.

In an exclusive interview, Amitabh Behar talks to Corporate Citizen about his 22-years of experience as a civil society leader and how he spearheads the organisation’s vision to fight against inequality, poverty and injustice in the country, besides carrying forward its humanitarian work. He was recently in the news for the recent OXFAM Report, which showed that 84% income of Indian households fell while a fistful of millionaires grew richer

Corporate Citizen: Tell us about your childhood days and what and who influenced you the most?

Amitabh Behar: Childhood was in Bhopal in a government family with my grandparents in Chhattisgarh. I was certainly influenced by my upbringing in which my parents ensured that the privileges that we had were not taken for granted. In fact, a deep empathy was inculcated to recognise one’s rootedness in the context that we lived in. Early in childhood, I was exposed to the newly emerging social sector then called the Voluntary Sector committed to social justice and human dignity for all.

CC: How and why did you choose a career that values social justice? Please chronicle for us your career graph.

With my childhood exposure to the voluntary sector, the idea of social justice became a driving force in the choices I made. While studying at JNU, I developed a more nuanced understanding of how society and politics function, and millions of people are not able to access a decent life due to structural causes. Throughout my career, I have worked with Indian NGOs, large funding foundations and bi-lateral agencies primarily focusing on research and advocacy. Over the last several years, I have played more of a leadership role for the organisations I am part of but also for the social sector.

CC: As the CEO of Oxfam, what are your roles and responsibilities?

As the CEO, it is my duty to represent Oxfam India and build an effective national presence for influencing, campaigning, and fundraising while providing leadership, vision, and strategic direction for designing and implementing programmes. It is my responsibility to ensure that we as Oxfam India, enable a discrimination-free India for the most marginalised communities.

"We don’t even know there is such a thing as a truly free market capitalism. In India, capitalism works as a mechanism to generate and concentrate wealth in the hands of the few and this has led to a stark inequality in India"

CC: How do you view capitalism in India? What are its pros and cons?

The current form of capitalism in India is not free-market capitalism. We don’t even know there is such a thing as a truly free-market capitalism. In India, capitalism works as a mechanism to generate and concentrate wealth in the hands of the few and this has led to a stark inequality in India. We are now marking 30 years of economic reform since the 1991 reforms which ushered in an era of high growth, declining poverty, a burgeoning, aspirational middle-class and the very real possibility of a seat on the global stage.

However, our reality today is structural inequality and two-faced capitalism-partly dynamic, competitive, productivity and growth-oriented, but coexisting with an increasingly visible, dark side entrenched in rent- seeking extremism that privileges political deals over the rules-based business and neglects distributional policy as well as weakens human capabilities by undermining the social sector.

CC: What are your thoughts on the attitude of the rich in India regarding paying taxes? Please also elaborate on taxation inequality and tax evasion.

Since 2014, a huge number of documents – including the Panama Papers and the Pandora Papers scandals have been leaked by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) unveiling how tax evasion and tax avoidance have become standard business practices across the globe. Indian cases are also highlighted in these reports. Thus, taxing the super-rich has great potential to generate resources for social sector spending in India.

Research reveals that 1% tax on the richest 10% can provide the country with nearly 17.7 lakh extra oxygen cylinders, while a similar wealth tax on the 98 richest billionaire families would finance Ayushman Bharat, the world’s largest health insurance scheme, for more than seven years. There is a need for the government to implement inheritance tax and wealth tax which result in redistributing income since a part of the wealth goes to the government. This widens fiscal space for the government to plan and spend for the poor.

CC: You mentioned that the one per cent wealth tax of 98 richest persons in India could help in the education of the poor. Could you please elaborate?

Yes, estimated resource accrual through the implementation of wealth tax on 98 richest individuals in India would be enough to finance the total annual expenditure of the department of school education and literacy under the Ministry of Education. Another estimate suggests that four per cent of the tax on the wealth on the 98 billionaires can take care of the Mid-Day-Meal Scheme of the country for 17 years or Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan for six years. This is estimated from the Credit Suisse data on wealth of 142 billionaires in India.

CC: You are recognised for your governance accountability. What has been your role over the years?

I have worked on the issue of governance accountability with the primary premise that democracy is a work in progress and civil society must play an important role in seeking accountability from power and government, as the primary source of power should be accountable to the people. Over the years, I have realised that the question of holding power/government to account is a demanding task and is often resisted and therefore, it is important to use strategies that are collaborative in approach but do not lose the lens of accountability. It has been gratifying to work on three particular aspects of governance accountability-institutional accountability, political accountability (holding govt. to the promises they make in manifestos, policies and schemes) and budgetary accountability.

"The time is ripe for India to reintroduce a wealth tax to generate much-needed resources to fund the recovery from the pandemic. Tax compliance by wealthy individuals must also be drastically improved, instead of imposing indirect taxes on India’s poor and middle-class. We also need to generate revenue to invest in the education and health of future generations"

CC: Your report points out the obscene inequality between the rich and the poor in India. What needs to be done?

One thing to do is to redistribute India’s wealth from the super-rich to generate resources for the majority. The time is ripe for India to reintroduce a wealth tax to generate much-needed resources to fund the recovery from the pandemic. Tax compliance by wealthy individuals must also be drastically improved, instead of imposing indirect taxes on India’s poor and middle-class. We also need to generate revenue to invest in the education and health of future generations.

The primary outcome of the Covid-19 pandemic must be a quality, publicly funded and publicly delivered healthcare system that works for all and not just the rich. A secondary outcome should be an education system, which addresses the needs of everyone, not just those privileged to attend elite private schools or have access to digital technology. It is time to reverse social and economic policies that have contributed to the poor development outcomes for India’s marginalised communities.

It is time to reverse privatisation and commercialisation of public services, address jobless growth and bring back stronger social protection measures for India’s informal sector workers. All these things will help address the inequality we see in Indian society.

CC: Could you throw light on the unorganised sector and lack of social security? What is the solution?

India’s informal sector comprises almost 93 per cent of the total participating labour force in India which is about 450 million workers who face high risks to their human and labour rights, the dignity of livelihood, unsafe and unregulated working conditions, and lower wages among many other vulnerabilities. Research shows that successive governments in India have sought to address the legislative deficit on the matter by operationalising schemes that address various components of social security. This approach has been piecemeal and has resulted in a highly disaggregated and fragmented framework whose administration depends on several variables such as nature of employment, the income of worker, or income status of the worker’s household.

The Code of Social Security, which was introduced in 2020, at least in principle, has the potential to significantly expand the coverage of social security especially when it comes to the unorganised labour force. However, the code does not state social security as a right nor does it set a date for enforcement. Responsibility for enforcement of the code now lies with the contractors who are themselves marginalised by larger corporations. It is also totally silent on ancillary issues such as workplace safety and equal treatment of permanent and contractual workers.

To address informal sectors’ workers’ issues, it is necessary to enact and enforce statutory social security provisions for them. While the government is recognising gig economy workers, it also needs to focus on laying the legal groundwork of basic social sector protections for 93 per cent of India’s workforce. There is also the need to work on the knowledge of social security schemes among this group as many risk missing out on benefits that they are entitled to. Therefore, local governments and workers’ welfare boards should inform and educate workers in their jurisdiction, about available social welfare schemes, employee benefits and legal rights.

Work also needs to be done to reduce administrative and registration barriers in these schemes currently, the registration of potential beneficiaries in social security schemes is difficult to navigate and a long-drawn process. It is also pertinent that employers are provided with a clear set of guidelines on the compliances required under the law. This includes the issuing of a mandatory written contract of employment, payment of wages within 30 days of work and guaranteed basic pay in the face of any crisis.

CC: What do you think of the present government’s FCRA license policy, because of which Oxfam has also suffered? What is its adverse effect?

Oxfam has been doing a tremendous amount of work ranging from setting up oxygen plants to ensuring livelihood for poor women-a significant part of this work gets disrupted due to the non-renewal of FCRA license. It is important that FCRA is used to facilitate the good work done by the social sector and is not a bureaucratic hurdle.

CC: Education and health are drivers of an equal society. Such a nice thought. Please elaborate

Let us talk about healthcare first. The poor state of public-funded healthcare in the country has pushed the majority of the population to resort to the private sector to obtain this service, raising one’s out-of-pocket expenditure. Similarly, education is critical in the fight against inequality. Increased spending on education has been identified by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to be a vital part of a package of policies critical to tackling inequality. Globally, countries with higher mean years of schooling tend to have lower income inequality. Inadequate expenditure on health and education go hand-in-hand with the rise in the privatisation of the provision of essential goods, thus, increasing inequality in the country.

"To address informal sector workers’ issues, it is necessary to enact and enforce statutory social security provisions for them. While the government is recognising gig economy workers, it also needs to focus on laying the legal groundwork of basic social sector protections for 93 per cent of India’s workforce. There is also the need to work on the knowledge of social security schemes among this group, many risk missing out on benefits that they are entitled to"

CC: The impact of the pandemic economically is shocking as per your report with 84% of households have seen income decline. Please share more details.

Covid-19 has widened economic inequality in almost every country at once. Rising inequality means it could take at least 14 times longer for the number of people living in poverty to return to pre-pandemic levels than it took for the fortunes of the top 1,000, mostly white male billionaires to bounce back. Billionaires in India increased their wealth exponentially since March 2020 when India announced the world’s biggest Covid-19 lockdown and the economy came to standstill. On the other hand, data has shown that 170,000 people lost their jobs every hour in the month of April 2020.

According to a Pew research report, the estimated number of the poor in India was projected to be 59 million in 2020-24, however, this number doubled to 134 million during one year of the pandemic. The pandemic has not only pushed vulnerable sections into poverty, but has also disproportionately affected girls, making them more vulnerable to child marriage, early pregnancy, and gender-based violence. There is a lot of literature and data available on this.

CC: You have done notable philanthropic work during the pandemic. We would love to hear about it.

Oxfam India’s Covid-19 response ‘Mission Sanjeevani’ is one of the largest among NGOs in India. Under the initiative, Oxfam India provided seven Oxygen generating plants and distributed over 13,388 life-saving medical equipment such as oxygen cylinders, BiPAP Machines, concentrators, and ventilators, over 116,957 safety and PPE kits, over 9929 diagnostic equipment such as thermometers and oximeters, and 20,000 testing kits in 16 states. We reached over 150 district-level hospitals, 172 Primary Health Centres, and 166 Community Health Centres.

We trained and provided safety kits to over 58,600 ASHA workers in 10 states who are the backbone of the primary healthcare system. We have delivered food ration to over 5.76 lakh people. And made cash transfers to over 12,000 people to the tune of INR 5.44 crores to help them with their immediate needs during the pandemic.

Since March 2020, Oxfam India was at the forefront whenever Prime Minister Narendra Modi called upon NGOs and civil society to join the fight against COVID-19 by helping the government to strengthen health services and accelerate pace of the vaccination drive. The Supreme Court also acknowledged the contribution of NGOs in providing relief during the pandemic.

Education is critical in the fight against inequality. Increased spending on education has been identified by the IMF and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to be a vital part of a package of policies critical to tackling inequality

CC: Time to end patriarchy. How should society go about it?

Patriarchy is deeply embedded in society; some of the domains are the Family, Community, Institutions (such as Schools-Colleges, Banks and Financial Institutions, the institution of Law) and the Market. Patriarchy will need to be addressed and eliminated in all these spaces. At the same time, patriarchy is systematically taught to people through education, socialising and enforcement of social norms. These will also have to be undone to stop its perpetuation. For example, it begins with the anxiety to pin particular sex on a newborn baby, gender socialising at an early age, textbooks in schools, play-toys, dress, customs and traditions, rules of mobility, higher education and career choices, reproduction, politics, all spheres are invaded by patriarchy and used in socialising girls, boys and other genders. This is a mammoth task, but it needs to be started. It is also a highly complicated task, as patriarchy stands engulfed in other axes of power namely caste, class, religion, ethnicity and sexual identity and orientation.

Oxfam India has launched an online gender equality course which is in both Hindi and English and very interactive, using dialogues, quizzes and short clips to bring home the politics of patriarchy and gender discrimination. We did this because we have a specific focus to work with youth. It is meant for young people between the ages of 15 and 25 years. Understanding this system is the first step towards taking any stand against it or slowly dismantling it in your own life.

As feminists have said, personal is political - you need to begin with yourself. This is one step to counter gender socialising. Similarly, the women’s movement organisations are working to remove patriarchal stereotypes from textbooks, from the courts, from law books, from the entertainment industry, which has huge soft power and hence, important to call out (Oxfam has also successfully used Unstereotype Cinema as a capacity-building tool to have dialogues with young people). Medicine, gender gaps in various domains, most importantly in women’s work, access to the property, equal wages, equality in public spaces, political and other forms of representation are other areas that should be focussed on. All these domains will need to be tackled, and as mentioned above, newer forms of patriarchy will need to be tackled using the intersectional lens of gender, caste, class, religion, ethnicity and gender identity and sexual orientation to truly make a difference.

CC: The health infrastructure in this country is starved of resources. What should be the government’s political choice for the conscious investment of our energies and political prioritisation of health?

Well first, we should increase health spending to 2.5 per cent of GDP to ensure a more equitable health system in the country. Then we should ensure that union budgetary allocation in health for SCs and STs is proportionate to their population. The government must monitor the spending under these heads via a special monitoring cell. We can prioritise primary healthcare by ensuring that two-third of the health budget is allocated for strengthening primary healthcare, specifically health and wellness centres, to ensure accessibility of services to all, including those living in the remotest parts of the country.

The Centre can also suggest that state governments allocate their expenditure on health to 2.5 per cent of GSDP (Green Skill Development Programme). States should be allowed a higher degree of autonomy on spending funds received from the Centre through centrally-sponsored schemes and the flexibility to reallocate funds to issues that might be of higher priority in a state. The Centre should extend financial support to the states having a low per capita health expenditure to reduce inter-state inequality in health.

There is also a need to widen the ambit of the insurance schemes to include out-patient care. Major expenditures on health happen through out-patient costs such as consultations, diagnostic tests, medicines, etc. It becomes particularly exorbitant for patients with chronic illnesses and those requiring long-term care.

The current government-financed health insurance schemes only cover hospitalisation cases. Moreover, the second wave of Covid forced a large number of people to recover at home due to the shortage of beds incurring significant expenses that are not eligible for reimbursement under the existing insurance policies that require hospitalisation to be eligible. While the report does not endorse government-financed health insurance schemes as a way to achieve UHC and stresses that insurances can only be a component of it, it is imperative that government-financed health insurance schemes widen their ambit to include out-patient costs.

Finally, it would also be essential to earmark funds for the provision of free essential drugs and diagnostics at all public health facilities. The current National Health Mission Free Drugs & Diagnostics Service Initiative is only a set of guidelines; it is not statutory as a scheme and therefore, not necessarily enforceable. Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu, however, already have a scheme for free medicines in place that increased the footfall of patients to public health institutions considerably. A national scheme, that includes not just drugs but diagnostics as well, should be introduced to reduce OOPE on health. Concurrently, budgetary allocations for the Janaushadhi Pariyojana, which provides free medicines at select outlets, should be increased.

"Indian stock markets do not reflect India’s economic realities. Indexes such as Nifty and Sensex are dominated by sectors such as financial services, telecom, and IT which do not represent the Indian economy"

CC: Have the democratic systems in a way, failed in the capability of wealth redistribution and inclusive growth, in India as well as other democracies?

Well, democracy in itself can do very little to advance wealth redistribution and inhibit inequality unless supported by policies that support these ideas. Three key features of democratic politics can make this outcome possible. When societies are divided along lines other than wealth, for instance in India, you have caste and increasing religious intolerance. This can inhibit the adoption of wealth-equalising policies. Likewise, voter preferences for the redistribution of wealth depend on the beliefs they form about the fairness of these measures, and some voters without wealth may feel that redistribution is unfair, such as those in the first generation entrepreneurship for instance. Finally, wealth-equalising policies may be absent if the democratic process is captured by the rich. If the wealthy are able to exert a disproportionate influence on the government despite the principle of one person–one vote, then they may use this influence to block policies that equalise wealth. This is true of countries with billionaires and business monopolies and monopsonies.

CC: We see our stock market booming, breaking all records, and reaching new highs. Do you think the stock market seems to be operating in another unequal silo, given the number of Indians on the verge of extreme poverty? How do you see this scenario?

Indian stock markets do not reflect India’s economic realities. Indexes such as Nifty and Sensex are dominated by sectors such as financial services, telecom, and IT which do not represent the Indian economy. As we all know, most of India’s employment tends to be in SMEs, manufacturing, trading, and most of all in agriculture, which has a minuscule representation in the stock market.

Even if one had to use terminology familiar to stock market analysts - the real indicator to look at would be what is called Buffet’s indicator or the ratio of equity market cap to the Gross National Product of a country. What this indicator does is measures if the index in question is overvalued i.e. the trading value is a bubble or unreal or is real and therefore, sustainable. Over the last quarter of last year and early this year, this indicator has fluctuated between 115 to 122 both of which are unreasonably high, meaning the optimism is unreal. Similar ratios such as the P/E (price to earnings ratio) or CAPE all point to overvaluation.

Then, of course, there are the real indicators of India’s economy - record - high fiscal deficit, all-time high unemployment, falling labour force participation, a return to agriculture, high MNREGA demand etc., these are the truth of India’s economy - not the share market.

"How ethical a corporate or business house is can be understood when the volume of its philanthropic activities is measured (relative to other businesses) and more importantly, when its record on labour or worker welfare is considered. As a sector, the best indicator is to look at the welfare status of the worker and the simplest indicator here is wage"

CC: What are your observations on India’s corporate world in terms of corporate ethics and employee/labour workforce salaries?

How ethical a corporate or business house is can be understood when the volume of its philanthropic activities is measured (relative to other businesses) and more importantly, when its record on labour or worker welfare is considered. As a sector, the best indicator is to look at the welfare status of the worker and the simplest indicator here is wage. According to the Minimum Wages Act of 1948, the purpose of seeking employment is to sell labour to earn wages to attain a ‘decent’ or ‘dignified’ standard of living. The wage or income that a worker obtains from his/her work is, therefore, what enables him/her to achieve a fair standard of living. The Act states that one seeks a fair wage, both, to fulfil one’s basic needs and to feel reassured that one receives a fair portion of the wealth that one works to generate for society. The same Act also states that society has a duty to ensure a fair wage to every worker, to ward off starvation and poverty, to promote the growth of human resources, and to ensure social justice without which, likely threats to law and order may undermine economic progress.

The Code on Wages, 2019 which aims to regulate wage and bonus payments is relevant to the informal sector workers, particularly because of the clause on minimum wages. The Code prohibits all employers from paying wages below the minimum standard which the centre or the state governments notify. India’s national minimum wage has remained the same since 2020 at INR 178 per day. The Satpathy Commission in January 2019 recommended changing the minimum wage to INR 375 per day or INR 9,750 per month with regional variations, based on consumption expenditure and employment data. However, the Ministry of Labour and Employment just increased it by a meagre 1.13 per cent, from INR 176 per day in 2019 to INR 178 per day. The data from the last census (unfortunately, we don’t have newer data) shows that while the average worker was being paid INR 247 per day in 2011–12, the median wage is only half of the already measly average, i.e., INR 150 or less. So, in terms of salaries, India’s workers are not doing well.

CC: Tell us a bit about your family

I live with my daughter and wife in Delhi. My daughter is 14-years-old and has recently written a strong feminist poem and is a huge fan of BTS (Bangtan Boys, a Korean music band) - we had not discovered the Korean culture the way her generation is engaging with it. She has learnt Korean language on her own. My wife is a community medicine doctor and believes that the health sector in this country must focus on public health and not on curative specialisations.

CC: What is the philosophy of life that you live by? Please round it up in four to five sentences…

I do believe that life has to be a meaningful journey and only a normative framework can provide that to us. My normative framework is rooted in the ethos of justice, liberty and human dignity. While this normative framework guides the philosophy of life, it also is rooted in the idea of recognising that equanimity in life is critical for our well-being.

About Oxfam

Oxfam India is a movement of people working to end discrimination and create a free and just society. Oxfam has been in India since 1951. In 2008, Oxfam India became an independent affiliate and an Indian NGO. Oxfam India is an autonomous Indian organisation and has staff and board members from within India. Oxfam India is a member of the global confederation of 20 Oxfams across the world. The Government of India has registered Oxfam India as a non-profit organisation under Section 8 of the Indian Companies Act, 2013 and have a Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) license. In the last ten years, Oxfam India has responded to disasters in Assam, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Kerala, Kashmir, Manipur, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Odisha.