Mahatma Gandhi’s Economic Philosophy

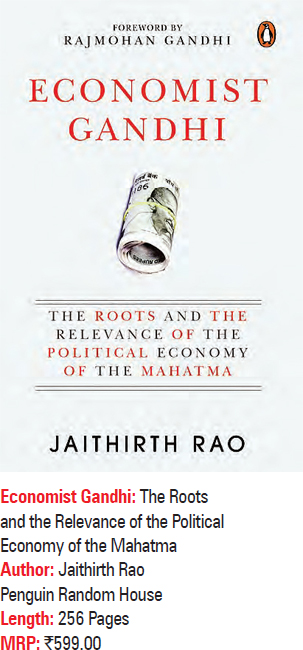

Why do we need to look at Mahatma Gandhi as an unlikely management guru and an original thinker who enriched the discourse around market capitalism? To find Gandhi’s positive approach towards business and a relatively unexplored facet of Gandhi, the Pune International Centre held an online conversation recently on the latest book, “Economist Gandhi”, by Dr Jaithirth Rao, which explores Mahatma Gandhi’s economic philosophy. The conversation with Jaithirth Rao was chaired by Kiran Karnik, Former President, NASSCOM. This profound book is the result of a lot of work and research and the Gandhi unveiled by Jaithirth Rao is brilliant, unexpected and daring. Jaithirth Rao is an entrepreneur and founder and former CEO of Mphasis, a software company. Rao held several positions in Citibank prior to his founding Mphasis in 1998. In a banking career of over 20 years, he served with Citi and its parent Citicorp in various capacities. Rao is a recipient of several distinguished business and government recognitions. He has also been the chairman of NASSCOM.

Corporate Citizen brings you the riveting discussion, wherein Jaithirth Rao brilliantly unveils Gandhi, providing insights into a hidden facet of Gandhi’s personality, his thoughts on economics and capitalism and more.

"I am very fascinated by Gandhi’s very childlike sense of humour, the ability to deal with contradictions, the ability to transcend contradiction and always be insightful. We should prescribe extracts of him, both in business schools and economic departments"

- Dr Jaithirth Rao

Kiran Karnik: Very few of us looked at Gandhi as somebody who had a sense of humour, or a smiling man, or had this impish sense. For decades Gandhi has been an icon and there would be hardly a person in this country, who doesn’t in some way swear by Gandhi-his ideas, his idealism, his very humanity.

Jaithirth Rao: The problem with Gandhi really is that he has two facets-he has an Indian reaction, and ours tends to be typically guided by current political controversy. So, we will be keep raising the question, was Gandhi right in doing, Quit India Movement? Was he right in calling of Satyagraha after Chauri Chaura incident? Was he right in supporting the Khilafat movement? These are seemingly hundred-year-old questions, but they are actually pertinent to current political discourse.

Outside India where Gandhi is a very important figure, he is primarily seen as a political strategist, a political thinker and a moulder of public opinion. So, there are very few scientific political courses in any university in the world where there is at least one or two sessions on Gandhi and his strategies. The rest of Gandhi’s intellectual contribution tends to get ignored. The point I would like to make is that when you talk about an intellectual, when you talk about a Karl Marx, the thing that you immediately say is that Karl Marx demonstrates intellectual continuity. With Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who in turn demonstrates intellectual continuity. So, you see them as part of the intellectual history, not as some isolated people speaking. And, that is one of the central points in my book.

Equity is unique to English Common Law

I want to position Gandhi as a result of diverse intellectual inputs that went into him, and I have identified few key ones, particularly with respect to political economy because my book is not on Satyagraha, which is a topic that has been covered by so many people, so many times. This is about Gandhi’s political economy and I look at Gandhi as being a child of English Common Law. The principle of equity is unique to English Common Law and Gandhi was a great fan of it. The word trustee and trusteeship is unique to English Common Law, it’s a uniquely English idea. So, there is one source of Gandhi’s intellectual traditions.

Bania, a commerce-state craft tradition

The second is one that I call the Gujarati-Bania-Vaishnav-Jain tradition, which is a very old tradition again. Which has got its own concept of what constitutes business ethics. And, the greatest example is Shantidas Jhaveri, who actually paid from his pocket, in order to save the city of Ahmedabad from attackers and as a result all the merchants of Ahmedabad got together and said you are the Nagarsheth and starting tomorrow certain small tax will be levied and that will accrue to you. So, there is this political-economic involvement. My friend Chhaya Goswami has actually made it quite clear that Gujarat Kutch was one of the few places where the Dewans of the state were usually Banias, they were not Brahmins, which might have been the case in Thanjavur or Travancore. So, this connection between commerce and state craft (political economy), is an old Gujarati tradition.

And there is also a trusteeship tradition, which Gandhi clearly identified with. The old organisation, or firm, or trust of Anandji Kalyanji which is there in Gujarat, looks after all the Jain temples in western India and their idea of trusteeship is quite unique. It’s similar to English Common Law but not the same. There the trust does not own the property, the property actually belongs to Adinath Bhagwan-temple belongs to the presiding deity of the temple and the trustees just manage Adinath’s property.

"Outside India where Gandhi is a very important figure, he is primarily seen as a political strategist, a political thinker and a moulder of public opinion. So, there are very few scientific political courses in any university in the world where there is at least one or two sessions on Gandhi and his strategies"

Ishavasya Upanishad, a central Vedantic idea

The third source of Gandhi’s ideas really is the Ishavasya Upanishad. Gandhi has gone on record that if all other Hindu scriptures are destroyed, but if the first stanza of Ishavasya Upanishad is preserved, then Hinduism will still survive. As many of you know, it is a Yajurvedic short Upanishad in verse and the opening line, “īśāvāsyamidam sarvam”, is a very central Vedantic idea. which means all moving objects in the world are energised or pervaded by the energy of the Lord, and that becomes very important for Gandhi. If that is the case, then wealth becomes a secondary issue. By definition the world belongs to the Lord, so the wealth belongs to the Lord and we are here only to manage it. And so, he is able to expand the English legal concept of trusteeship to a larger concept, that it is the duty of all wealthy people to look on their wealth as a trust.

The parable of the tenets in the Gospel

The fourth area where Gandhi has influenced is the Gospels, particularly of Mark and Matthew-he knew them by heart. Professor Anthony Parel, an Indian professor who lives in Canada, has done the best summarization of Gandhi’s famous 1916 speech to the Economic Association Muir College Allahabad, where he talks about political economy and its very clear. Although he claims he doesn’t know much about Adam Smith, Alfred Marshall and David Ricardo, actually he does. It’s an extraordinarily scholarly speech through which Gandhi the scholar and the intellectual comes true and you can see how he weaves in the Ishavasya idea and the ideas in the Gospel. The parable of the tenets in the Gospel actually tells that wealth is not a bad thing, it is something that talented people are supposed to invest in and create it. But, Christ is also very clear that ‘thou cannot worship God and Mammon both’. If you do-Mammon is a god of wealth-then you are bound to go to hell. Gandhi is able to see this and he concludes that wealth is instrumental, you can and you should acquire wealth, but you cannot love it and worship it. So, he has taken the Ishvasya and Gospel’s ideas and blended them together. And somewhere in that speech he calls Christ, the greatest living economist of his time. It tells you the kind of experiments Gandhi was able to contemplate and actually indulge in.

Maternal view of the Gita

The Gita is the most controversial, of course-the “non-violence” people have a big problem with Gita influencing Gandhi, because Gita after all is supposed to justify a war and so how can Gandhi get influenced by it. Gandhi is very clever-this is where I found Gandhi to be impish and clever. He basically says, “Gita is whatever I say it means”. He takes the right to say so, and by the way that is not unusual in India. The idea that Bhashyakaras and Tipanikaras or the commentators and note-givers to all Vedantic texts, are entitled to make radically new interpretations, and it goes back to Shankara. It’s a very old thinking in the Indian Vedantic thinking and it is allowed. So, the idea that a person can have his/her own interpretation, is an Indian tradition that Gandhi grabs. And he has a very maternal view of the Gita-he refers to Gita as his mother. So, he is able to soften all the violence part.

The point I have made in my book is that Gandhi read the Gita first in Sir Edwin Arnold’s translation “The Song Celestial”. Sir Edwin Arnold was a high-charged English Anglican Protestant and he talked about the Protestant ethic as being central to the Gita. And therefore I see parallel between Gandhi and Max Weber’s view of the Protestant ethic, however he himself would disagree-he had great contempt for India and Indian traditions. But, I still see Gandhi and Weber on similar pages, when they look at wealth. Because, Protestant ethics-you are not supposed to indulge in conspicuous consumption, which is what the high Protestant ethic is.

So, I have given you five – English law, Gujarati-Bania traditions, Ishavasya Upanishad, the Gospels, and the Gita, in a very eccentric way, admittedly eccentrically interpreted by Gandhi.

Gandhi was influenced by the Quakers

There is small sub-text-Gandhi was influenced by the Quakers, who were a sect of non-conformist Christians. They were some of the earliest opponents of slavery and for prison reform. They also have very strong objections to inherited wealth and they use towards stewardship and not trusteeship as a way of wealth. Gandhi had a lot of Quaker friends and was close to them.

Catholic Trappist Monastery

There is another subtext-Gandhi’s favourite economist was a man called J. C. Kumarappa, who came from a Tanjore Protestant Christian family and who had imbibed a lot of Pietist tradition from Tranquebar. So, there is a Christian-Pietist thing and Gandhi himself had visited the Catholic Trappist Monastery outside Durban. So, even within Christianity there was multiple influences that Gandhi picked up.

"I want to position Gandhi as a result of diverse intellectual inputs that went into him, particularly with respect to political economy, because my book is not on Satyagraha, it is about Gandhi’s political economy and I look at Gandhi as being a child of English Common Law"

Connections between Gandhi and Adam Smith

So, all these things when I put together, I say, what is Gandhi’s political economy about and what parallels do I see in the thoughts of other economists? The first of course, we all have to go back to Adam Smith, the father of economics. I was kind of grappling with “The Wealth of Nations”, that it is all about selfishness and there is no connect to what Gandhi is all about. Until in conversation with Amartya Sen, he told me to stop “The Wealth of Nations’ and go back and read Smith’s earlier work, “The Theory of Moral Sentiments”. The moment I did that, I could see a solid set of connects between Gandhi and Adam Smith, the moral philosopher. We do a great disservice to Adam Smith, by teaching only one sentence about the Butcher and Baker and the exchange sentence from “Wealth of Nations”. I think, our students loose out. There is a whole part of Smith, which has a lot of connections with Gandhi. Including, by the way, Smith was a great opponent of East India Company and British Imperialism in India, 150 years before Gandhi was an opponent. There is a lot of congruence with their ideas.

Gandhi inverted the identity pyramid

Then I looked at some modern economists and the area where I found greatest was Richard Thaler’s “Behavioral Economics” and a specific sub-set of that, the George Akerlof and Rachel Kranton’s “Identity Economics”. Basically what Akerlof and Kranton say is that, we are not only wealth maximizers as individuals. So, this whole issue of being praiseworthy and seeking praise, both Gandhi and Smith have kind of dealt with it. Gandhi had to deal with some specific identity issues. Most of the issues that Akerlof and Kranton deal with is race and gender in the American contest. Gandhi had also to deal with caste in the Indian contest. And here there is a beautiful book by Nishikant Kolge, who shows how Gandhi inverts caste issues. Till Gandhi came along, lower caste leaders as well as upper caste leaders would tell Dalits and lower caste people, to start imitating the upper caste. This Gandhi said no, because Gandhi and Hind Swaraj had been totally against Indians imitating the British. What he said is that we don’t want to become like them, we have to imitate their best parts, which is their Bible and not their worst part, which is their guns. So, instead of asking the lower caste people to imitate upper caste professions or vocations, he made his upper caste disciples to clean toilets, do leather work, etc., which were typically lower caste occupations. So, he inverted the identity pyramid.

"Gandhi and Hind Swaraj had been totally against Indians imitating the British. What he said is that we don’t want to become like them, we have to imitate their best parts, which is their Bible and not their worst part, which is their guns"

Karnik: Many intellectuals represented the continuity, whereas Gandhi brought in disruption in thinking in a very major way. But, many people looked at Gandhi as luddite, somebody who was anti-technology. What was your perspective on this, given all the research that you have done. Because there are indications which show that he wasn’t really so. He was concerned about how technology was used and concerned about making sure that people respect what they do with their hands. What was his perspective on technology vis-a-viz new economics?

Jaithirth: The thing about Gandhi is he said so many things in so many places that, socialist, communist, Hindu, Muslim, anybody can quote him and get away with it. Swaraj is central and in Swaraj there are large messages which are anti-machinery. So you can say that Gandhi was luddite, but there are many places that Gandhi is praising the machine. In his own life-he was a very good printer and he knew how to use printing press, which is a machine. The Charkha (spinning wheel) is a machine and he liked using it. He used loudspeakers-later in his life he used All India Radio. He was very much in technology-he was not running away from them.

There is this fascinating experience in William Shirer’s book on Gandhi. Gandhi has gone to London for a Round Table Conference and he makes a visit to Lancashire, to the cotton textile mills there, and he is taken on a guided tour through two-three mills by the mill owners. And, Shirer is walking next to Gandhi. Gandhi looks at Shirer and says, “These machines and these English mills, they are antic and outdated. Just come to Ahmedabad and see machines in our mills, they are modern machines”. So, you could see that the man was not anti-machine. He understood why English textile industry was falling behind and why the Ahmedabad textile industry was getting ahead. His relationship with machines is more complex than we would like to make it out.

Running through the Swaraj, I have identified a kind of psychology Gandhi had, that machinery may create a psychological anomie in human beings. And, this is not unique to Gandhi. There are people like Durkheim, great philosopher scholar Aldous Huxley, who had a worrying about machinery creating anomie and creating psychological disturbance, when human beings themselves become machines. It is an underlying theme in Swaraj, so I think his opposition to machines is more. Of course, some people say then why didn’t he say so. Why did he just criticized machines. Why didn’t he sit and say that this is what I object to. We have to be more nuanced when we look at Gandhi’s stuff. Infact he is more of the labour union leader in Ahmadabad for textile middle workers, as well as friend of the mill owners. So, if mills had closed down, he had lost two sets of friends. He managed these contradictions quite well.

Karnik: Would you say that he was before in time, in some of the ways?

Jaithirth: We are talking about a man whose ideas go back now hundred years, and that’s why I want young people in India particularly to revisit Gandhi as an intellectual. Not merely as a freedom fighter, that was there, but there are things we can get in strange contexts. Anomie is a context that I stumbled upon by reading his Swaraj 6/7 times-his horror is not just for machines, it is for what machines may do to us. He is worried about the human soul. These are the ideas Gandhi anticipated and this is important for a great philosopher or intellectual. You have to look at the contextual-Swaraj was written at a time when British ruled us and supposed to have impoverished us and therefore it was an objection to British Imperialism, and that is what colours most of his Swaraj.

You also have to look at that which is not context. For example, Gandhi used railways a lot, so, you can’t say he was against the railways. One of the things that he mentioned somewhere is that, because of railways diseases spread faster. So, suddenly the context of today’s Covid…and he is a politician busy doing so many things. He isrunning ashrams, and still he has the time to be able to make gem of an insight in context, which has nothing to do with him. That is why he is a genuine intellectual, who needs to be studied.

He did anticipate many things, for instance, on the issue of feminism. In modern northern Indian languages derived from Sanskrit through Apabhramśa, the word ‘Purush’ means man. If you go to a gent’s toilet, they would display the word Purush, which means only for men. Gandhi went back to Sanskrit roots, when he was discussing Purusharthas-he said no, this means the ‘Citadel of the self’. Actually one of Purusha translations is, the citadel of dawn and the word Usha is dawn and therefore it applies equally to men and women-artha, dharma, kama, moksha, is not relegated only to men. His insights on these issues are common to both sexes, to both genders and need to be addressed that way. For instance, I have mentioned that Gandhi attacked the hyper-masculine English boarding school bullying traditions, which they used to rule us. He suggested that feminine traits were not about cowardice, in fact they are about resilience and courage. So, here is may be a topic of research for young economists-if you increase the quotient of resilience and courage and other such feminine traits, in an organisation, does that organisation do better-than just having this hearty English boarding school bullying theory, ex-macho management style. I am saying these are worth exploring and these are ideas that we can trace back to Gandhi.

"We are talking about a man whose ideas go back now hundred years, and that’s why I want young people in India particularly to revisit Gandhi as an intellectual. Not merely as a freedom fighter, that was there, but there are things we can get in strange contexts"

Karnik: Tell us little bit about Nai Talim (New Education), education and working with your hands concepts of Gandhi.

Jaithirth: With Gandhi everything starts in South Africa. They are setting up Pheonix Settlement outside Durban. So, Kallenbach, Gandhi’s partner and friend, goes and visits the Trappist Monestery and learns how to make sandals-he already knows carpentry. In Pheonix settlement, carpentry, making sandals and gardening, become part-Gandhi had no choice. He had lot of his followers coming together, they are children. So, he had to become an educationist, whether he wanted it or not and he became a splendid one. He brought those ideas with him, and all his life. And then when Kumarappa, Marjorie Sykes and people like that came in touch with Gandhi-Gandhi was not that interested in university education, he was very much interested in school education. In every ashram he had to create a school, where he emphasised gardening, singing, carpentry, sandal making, drawing. Kumarappa and he came up with Nai Talim, which was really new learning. Basically he made it something desirable for the poor. Gandhi’s ideas are not backward ideas.

We know about this boarding school tradition, but there are other traditions of education in the west, particularly the Scottish tradition of James Watt. James Watt never went to college, he was an apprentice trainee in an industry and he became fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Every bulb that we use today is made of 40 or 60 Watts-so he is part of our science. There is a Scottish tradition, there is American tradition, where people learn with tinkering. Even in our own contemporary times, Steve Jobs represents that tradition. He was very concerned about the size of the iPad, about the eye and hand coordination. Gandhi was very particular about that and Gandhi was very friendly with Maria Montessori, who had established that objects are better than slate, blackboard and notebook, to teach children, so the left brain-right brain coordination is better. And, I think if we introduce some of Gandhi’s ideas, we may have a lot of success. Today we have made Indian education very academic and rot learning examinations. We don’t encourage left-brain right-brain coordination, we don’t encourage tinkering. We should go back to the Scottish tradition, rather than the English boarding school tradition. And, we should see how Gandhi’s and Kumarappa’s ideas can be used here.

Nai Talim got bad name for several reasons. One, it was basic education-so it was for the poor. Rich people will send their children to Doon School and not to Nai Talim schools. Two, there was this whole issue of Urdu-Hindi controversy, which is absurd because Kumarappa writes, the medium of instructions will be the spinning and drawing will be taught before writing. So, they could have easily dealt with that but they didn’t. So, all these things had given a bad name to Nai Talim, and free India completely discarded it. Only now with these Atal Tinkering Lab, a little bit is coming back. I hope we can do more of it and if we do, I think we imitate our Korean and Japanese neighbours more than just the Southern England boarding schools.

Karnik: Taking this forward on the higher education in the engineering of today, which involves thinking, classroom, computer and nothing on the floor.

Jaithirth: There was a person called G.D. Naidu, who was an inventor in Coimbatore, who ran his transport company, which the Government of India nationalised. He had made an electric motor-he was an inventor sixty years ago. They made him for some reason, the chairman of the board, of an engineering college. And he then said that 4-5 years course is not necessary, two years is sufficient and the other two years students should work on the shop floor, and we will examine them from what they learn on the shop floor. Madras University sacked him-forced him to resign. He was not allowed to, because the idea was only about classroom learning and passing exams. This has crept even into engineering, which was supposed to be the most hands-on discipline that we have-even in agriculture. Even in our higher institutions, we have classroom learning and exams-the idea of doing anything in laboratories, workshops has really gone away. And I think Gandhi emphasises that and we need to go back to that, because if we don’t, I think we won’t produce a Steve Jobs. His great contribution is his designs, his calligraphy-these are ideas which come from eye-hand coordination and fine motor skills, which are centre to tinkering as a medium of instruction and not just classroom rot learning. I do not say give it completely, we need classroom learning and other hands-on disciplines as well.

"Capitalism itself is at the crossroads, and only technocratic responses are not going to survive. If we don’t have responses in the realm of moral philosophy, democratic capitalism as we know it may die and may be replaced by northern neighbours authoritarian capitalist. We need to worry about that"

Kartik: Here is an entrepreneur working in technology space, former banker working with finance, and working with large multinationals-how on earth you as a person with more of capitalist bent of mind, look at Gandhi? What got you to Gandhi in the first place?

Jaitirth: I am a great admirer of British Raj and Gandhi spent all his life fighting the British Raj. So, for me to make this transition is quite extraordinary. I owe it to two people - Ira Pande at the India International Centre, she felt that given all the problems that we are having post Enron, corporate governance and all that, there might be things that we can learn from Gandhi. So, at that time I did some desultory work on Gandhi and I wrote a non-academic piece for the India International Centre, which actually quite a lot of people liked. Then I was discussing that with Shishir Jha at IIT Bombay and he said that you are on to something bigger, so just don’t abandon it, start taking a look at it.

Separately, Amartya Sen, pushed me to looking at Smith and Gandhi, as intellectual equals talking to each other across two centuries and 20 thousand miles, and look at economics not only as wealth maximisation or optimisation, but also as a discipline with a major moral part to it. So, all of them came together and I spent a lot of time, lot of years, bought hundreds of books on Gandhi, visited Ahmedabad, met with Samved Lalbhai, the current trustee of Anandji-Kalyanji NOPD, I got their Itihas, in Gujarati, translated into English. I visited Sabarmati, in between for some other reason I did go to Durban and went to Pheonix. So, all of this kind of catalysed and came together in a book-I am very fascinated by Gandhi’s very childlike sense of humour, the ability to deal with contradictions, the ability to transcend contradiction and always be insightful. There is not a single sentence, where he is not insightful whenever you do a content analysis of anything of Gandhi. Which is why going forward, we should prescribe extracts of him, both in business schools and economic departments. The Allahabad speech should be taught in economic departments. And also I would encourage in the same vain, teaching extracts from Smith’s theory of Moral Sentiments and not just his “The Wealth of Nations”, so that the students get a balanced view.

I think, we need to look back at syllabuses-we are constraining kids into thinking just value maximisation and market cap is all that matters in finance studies. We are running away from the moral stuff. Post 2008, I think Capitalism itself is at the crossroads, and only technocratic responses are not going to survive. If we don’t have responses in the realm of moral philosophy, democratic capitalism as we know it may die and may be replaced by northern neighbours authoritarian capitalist. We need to worry about that.

Kartik: Does this passion,your reading, your commitment and your responses, indicate that you have become a Gandhian now?

Jaithirth: I think I am an admirer of Gandhi and I don’t think he would have wanted me to become a Gandhian. He would have continued to enjoy jokes back and forth, rather than blind adulation. Certainly there are many aspects of Gandhi I disagree with and also there is this question of emphasis-I choose to emphasis something more than others. That’s the way you read a great intellectual. We call ourselves being inspired by a very brave, very original, very impish, very funny intellectual of the twentieth century.