CORPORATE CITIZEN CLAPS FOR SANGAY LAMA AND THE TSOMGO POKHRI SANRAKSHAN SAMITI (TPSS), A LAKE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE THAT HAS KEPT THE TSOMGO GLACIAL LAKE AT 12,406 FT AND ITS SURROUNDINGS LITTER-FREE FOR THE PAST DECADE

Sangay Lama

Sangay LamaA resident of Sikkim’s Thegu village, Sangay and TPSS representatives from the Worldwide Fund, state forest department, environment and wildlife management officials, gram panchayat, drivers’ and shop owners’ association have been on a mission conserving the Tsomgo (Changu) lake. Located 16 km from the Nathu La pass, connecting Sikkim to Tibet Autonomous Region, its accessibility attracts tourists and is also a water source for around 270 households in the surrounding villages of Thegu, Changu and Chipsu. The garbage menace, saw used milk cartons, packets of instant snacks, food wrappers, packaged bottles, tetra packs and sewage, being carelessly tossed away in the lake and its periphery, which also houses 180 local shops, adding to the pollution. In 2006, the state government issued directives for conserving the lake’s environment and in 2008, TPSS, a non-government body was formed to work in tandem with other local agencies. The first change they brought about was to move away all the shops along the lake’s vicinity to an alternate designated space. A waste management system was also put in place whereby all the waste generated in the area is collected and segregated, at the source. The 52 shops selling food, handicrafts and other commercial produce each generate around four kg of dry and two kg of wet waste which is collected at designated hours and disposed of at the local Martam Dumping and Recovery Centre. Tourists are charged Rs.10 as ‘Pokhri Sanrakshan Shulk’ (lake conservation fees). It helps meet the expenses in transporting and managing the waste, part of the revenue is shared with the government and also utilised for awareness drives, community services, helping tourists in distress, and other maintenance costs. Villagers also faced issues with the army station in the lake’s vicinity that released waste into the water body which was eventually resolved. For its efforts, the TPSS has bagged the state tourism department awards - Best Clean Tourist Spot Award for Changu (2013) and the Best Clean India Campaign Award (2019).

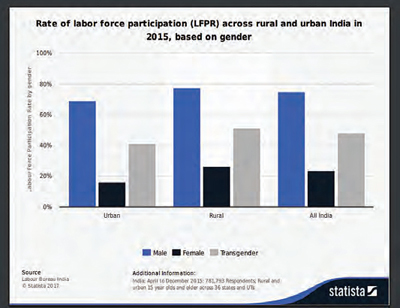

CORPORATE CITIZEN SLAPS INDIA’S INCREASINGLY LOW FEMALE LABOUR FORCE PARTICIPATION RATE (LFPR), WHICH IS LOWER THAN SAUDI ARABIA, AFGHANISTAN, AND PAKISTAN

The percentage of working-age women who are economically active in the country is far lower than the global average, attributing to India’s worst labour force participation rates (LFPR) by women. The fact is that only 1 out of 5 women in India work as per the latest 2019 World Bank indicators on India’s female LFPR. Experts have questioned the regression in the LFPR despite India’s higher GDP growth rate. The LFPR indicates the percentage of the total women within the working-age category who are seeking work and includes both employed as well as the unemployed-seeking work. A 2018 paper published by the World Economic Forum had estimated that India’s GDP would go up by 27% if the female LFPR was the same as that of their male counterpart. India’s low labour participation dates back to its cultural bias in its feudal and patriarchal attitudes; add to this is a lack of women’s safety and childcare centres. The decline in India’s overall female LFPR is also due to the falling rates in rural India. While the urban female LFPR was always low, the latest dip has been caused by fewer women in rural India being counted as part of the labour force. However, a 2014 ILO paper indicates more women enrolling for higher education that translates into a lesser number of women in the early years (15-29 years) of the age sample considered for female LFPR. A large group of women continue to be missing from the workforce, even in the higher age brackets, which is a cause for concern for policymakers. With the likelihood that many women with higher education are not choosing to seek employment or are facing barriers at home and the workplace itself, has forced them to remain outside the purview of salaried employment. Meanwhile, ‘unpaid’ housework is considered entirely a women’s prerogative irrespective of a woman’s employment status. Women’s empowerment is mere lip service if we do not sincerely improve the female LFPR, a means to uplift Indian women, which could become a lost opportunity.