"Management practices to nurture environment and sustainability"

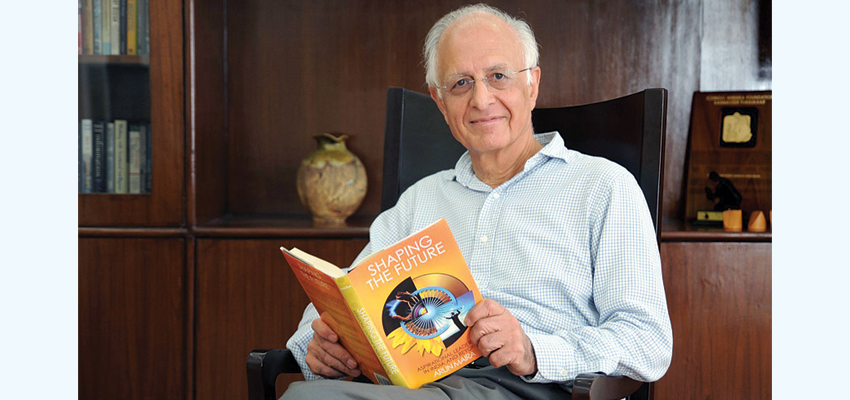

The third session of Tata Literature Live! Business Sutras, an ongoing series of live virtual events comprising of conversations and panel discussions with leading business writers and thought leaders, was held recently. It presented Arun Maira, well-known author and management consultant, and Naina Lal Kidwai, Chairman, Advent Private Equity, India Advisory Board, in a live conversation with James Crabtree, reputed author, journalist and academic. The conversation centred around the topic “How good management practices can nurture the environment and sustainability”. Corporate Citizen brings you the excerpts

Challenges And Objectives

James Crabtree : This was already, before the coronavirus pandemic, a critical moment for India’s environmental future. India is the world’s third-largest emitter of carbon, it will in a couple of decades be the world’s most populous country. It is widely accepted among climate experts that if India follows her path of development that is as carbon-intensive as China, it is going to be impossible for the world to achieve any kind of sustainable target. But even without that, there are a host of challenges India faces: air pollution and air quality that has risen up the political agenda in recent years; water and water shortages with droughts in many parts of the country; plastics and plastic pollution at a time when the global plastic recycling system is in crisis, and biodiversity to name but four. All the four of those areas are complicated by what is happening with the coronavirus pandemic it means that government, which was previously focused on areas like renewable energy, is going to be less so. And it means there could be less money to go around. It also means that business is distracted and that is the focus of our discussion

James Crabtree: What has been the record of Indian business and business leaders on environment and sustainability, and what needs to change in order for India to achieve its objectives in this area?

Arun Maira : The problem we are trying to solve is how we think about our responsibilities in the world, businesses as well as policy makers. India has been hit very badly. All the years that we have been celebrating that we were the fastest growing free-market democracy. The time I was in the Planning Commission, we had an international agency do a study for us comparing India to its peers the BRICS countries, the ASEAN countries and India’s South Asian neighbours. How were we doing in terms of growth? What it showed us was while our growth was faster than almost all countries other than China, we were doing the worst even compared to Nepal, because for every unit of growth we were destroying the environment more than anybody else was. For every unit of growth, we were producing the least number of dignified jobs. We are a country with the largest number of young people to be engaged and unless our economy is going to generate good, dignified work for our young people, we are not going to grow the economy, besides damaging the environment much more than every other country.

We had our policymakers with corporation sitting beside them in the front seat, directing the growth of the economy. A big bus the pressure was always to get to two trillion, then five trillion, move this big bus faster and faster. The people sitting inside the bus had safety belts and airbags; they were even being served French wine and cheese to be comfortable as they travelled. But there were also people clinging on to this bus, on the top and to the sides, and we weren’t even aware of them. And then, with the pandemic, the bus had to be suddenly stopped and we all got alarmed: Where did these people come from on the road? They collapsed right around us. They were part of this growth journey but they were not getting the benefits that some of us were able to get. The people who were driving growth, what were the instruments that they were looking at? There were two instruments they were paying attention to GDP and the stock market. These two instruments weren’t giving information about what is happening to the environment, jobs, inclusion, wages, and availability of health facilities. We weren’t paying attention to these things. We lost sight of the fact that our bus was destroying the environment, running fast over the grass, damaging the earth, as well as just not carrying people along. They were so vulnerable and have fallen in front of us now.

“Data shows that growth and sustainability actually go hand in hand. It would be very important for Indian policymakers to recognise that the environment does not provide breaks in that growth story”

- Naina Lal Kidwai

Naina Lal Kidwai : Alluding to the bus that Arun has spoken of, I hope it is soon going to be an electric bus, fuelled by renewable energy! The good news is that there are regulations with this order coming into our cities with the desire to make public transport in electric mode. Having worked in the sustainability space for the past 10-12 years, some of the global work that informs some of my thinking comes from the work of the new climate economy. Data shows that growth and sustainability actually go hand in hand. It would be very important for Indian policymakers to recognise that the environment does not provide breaks in that growth story, and therefore we do need to ensure that we can work this together. What is it that we need to do as we look at this problem? I put this into two buckets one is the large well informed companies who are driven by stakeholders, and the second is the MSMEs which are the mass of Indian employers and business. Regarding the former, what begins to drive their thinking? Often, it’s well-informed CEOs, and executive committees but the good news is what’s also driving them is large financial investors, particularly global investors.

I’ve sat on global boards where we have received 10 page letters never threatening from large investors listing what they expect from board members to ensure the company is moving along. They are not saying they are not going to invest but I think that is the hidden threat there, right? Any of our listed companies and the foreign portfolio investors that come in, have to be extremely mindful about investors and their decisions to invest or not. This drives good practices. The second one, which large companies and multinationals are very sensitive to, is communities around their factories. I can’t afford to pollute the water around which I work, I need to ensure that the health of people within my factory is maintained, as well as that of the villages from where the workers hail, whether it is water or hygiene. It is self-serving but it’s also a win it helps the community, it helps me.

The foreign banks have long had norms regarding industries they will not lend to, in terms of pollution and sustainability. There is now a code amongst Indian banks as well which could be stricter, better, to ensure that they maintain a standard under which they will not lend. On the MSME side, it’s a different story. The regulations are seen as too strict. Their heart is in the right place but there is inability. We have to make sure that the compliance norms that are set are realistic and also solve for the infrastructure in a way that we don’t pin it on every small company even as there is a responsibility of government to establish that network and make people pay for it.

“It is widely accepted among climate experts that if India follows her path of development that is as carbon intensive as China, it is going to be impossible for the world to achieve any kind of sustainable target”

- James Crabtree

Commitment Matters

James Crabtree: Speaking of the big Indian companies, have we got to a stage where the captains of Indian industry now pay lip service to sustainability but don’t do much about it. They try and cut costs in a market where consumers demand cheap products and therefore you can’t have much extra spending. How committed are the Chief Executives and leaders of India’s big companies on environmental matters?

Arun Maira : They like to be seen as being very responsible among their peers to look good. They are talking the same language about environmental responsibility that would apply in Europe or the USA, in the terms that are used there such as less carbon in the products and processes and so on. However, our corporate chiefs are not really listening to the people and the system around themselves—they are listening and talking to each other, in a cocoon about the things they do, rather than being accounting to the people. Some years ago, when I was in the Planning Commission, some responsible big guys from the corporate world as well as the NGOs who wanted to work with and support them, and the Ministry of Corporate Affairs felt the need to create a scorecard that Indian companies would voluntarily apply to themselves, to judge whether they are environmentally and socially responsible in the Indian context. They developed a set of national voluntary guidelines developed by the Indian industry but they haven’t been adopted. Why not? Just at that time, someone came with the idea that having to measure themselves in this manner and report it in public would be messy for some of the other companies. They then had the idea of asking companies to give two per cent of their profits every year in CSR. This is conceptually wrong because that two per cent is a painkiller for the pain that the corporate operations themselves have quite often caused to the environment and to society.

Solutions Ahead

“On one side, we must prevent people dying from COVID; at the same time we must ensure that people dying from other diseases, poverty and starvation must not increase”

-Arun Maira

James Crabtree: In order to reach the kind of objectives that we need to, it’s not enough simply to do CSR – you need to transform your business processes in various complicated ways that are often expensive. How much more challenging will this become in the context of the coronavirus and the economic recession which is going to follow?

Arun Maira : It is making our dilemma very stark. On one side, we must prevent people dying from COVID; at the same time we must ensure that people dying from other diseases, poverty and starvation must not increase. We must look at many things interacting with each other and find a system solution which improves general overall wellbeing; not merely keep people safe from COVID. In India, it’s more to do with not the environment immediately the environment is being taken care of because of the suspension of large business activities but livelihoods of people are very sharply affected. Business is being asked to keep paying people even if they cannot operate so people have money to buy food and carry on their other essentials. However, businesses say they don’t have the money to pay them, and they need to be provided relief. This brings back the dilemma: Are people existing to enable businesses to produce profits for themselves or do businesses exist to enable people to earn money and lead good lives? This matter of labour laws and payment of wages is, fortunately, being understood in the right way. In India, 95 per cent of the people were on very temporary, uncertain contracts anyway. Businesses didn’t need any further freedom to hire and fire people. The need for more social security has become a front-page discussion.

Naina Lal Kidwai : The water and sanitation story has fortunately stayed squarely in focus. Speaking for the companies’ boards I am on, there has been no scaling back on efforts in terms of the work they are doing in communities around them. There will always be the dilemma in terms of profit returns and doing the right thing on sustainability but there are many intersection points which are win-win and we have to find those and work on them. It’s not just about CSR—it has to be in the DNA of the organisation and that comes from ‘Am I the most water efficient company?’ Waste water recovery is a very big subject—I am amazed at the number of companies we are documenting at the FICCI Water Mission in this space. The area that doesn’t get enough attention is pollution but citizens raised their concerns and ask for accountability.

Arun Maira : Businesses in India and around the world must get disciplined in three ways…

1. Deeply listening to people not like yourself

2. Ethical reasoning; every religion says it’s notokay to be purely selfish and that you must care for people around. To teach people and those in business school to not test every tool you use with respect to whether they will produce more profit but if they will produce more goodness for people other than yourself.

3. Systems thinking; it’s about looking at many things together you must see the consequences of working on one part of the system and how it damages other parts of the system. A bold decision which solves a problem in one area could cause a great harm to the whole system.

James Crabtree: Over the last few years, before the pandemic, we saw in and outside India, a host of new forms of consumer activism, from the extinction of rebellion movement to the climate sitins of Greta Thunberg, to rise in veganism and activism against airlines. To what extent in India, will you find corporate India lagging behind its customers who want to change more desperately than business leaders?

Naina Lal Kidwai : For a long time in India we will continue to have value based purchases; people looking at the cost, ensuring that there is a minimal quality to it but the quality will come more from safety than the environment per se.

The young generation, children, in particular, are becoming more and more aware but are we going to see a movement, particularly like it’s happening in Europe. We are still a while away but it’s also a very connected world. It needs catalysts, and if they are nurtured maybe we will see this happen. But it will remain urban, educated activism instead of mass activism which is what I would like to see, where the poor and every individual is part of that movement. We have seen very successful rural movements such as the tree protecting Chipko movement and the many water body conservation efforts happen at the village level but India is too vast and diverse. There are too many pulls and pressures in different directions, to give us quite the unifying that we see in Europe.

James Crabtree: Can India have a green new deal in the aftermath of the pandemic?

Arun Maira : The needs of people in India are not exactly the same as the needs of people in Europe. In India, we cannot separate the green movement from the people’s movement. I sit on the board of the WWF and they found that in India you have to protect the livelihood of the people otherwise you cannot protect the tigers and the mangroves. The people must protect their own environment because they care for it. They quite often use the environment very well; it is industries who come in and make them do things that destroy the environment. So you listen to the community and help it to find a sustainable solution for themselves. The solution for the world has to be every where local systems solutions which communitiesimplement and thus we will solve these big systemic problems around the world. Strengthencommunity governance in our country and the environment will get taken care of.