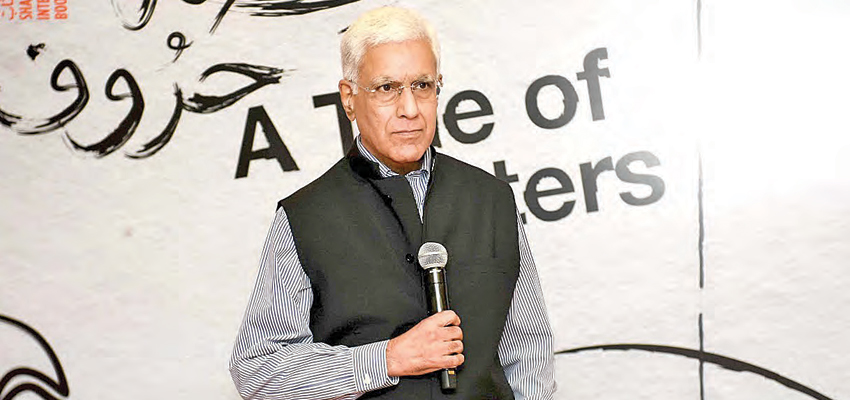

A Critique of Indian TV News

One of India's prominent television anchor, Karan Thapar has hosted the renowned TV news shows like The Devil's Advocate and The Last Word. At the recently held Dileep Padgoankar Lecture Series webinar, senior journalist and news presenter, Thapar, spoke on what worry's him about the state of Indian TV news today and what's going wrong. He talks about what defines a journalist, what today's news channels should be looking for in the real news and his journey from being a young reporter to what he is today, a wonderful interviewer

Journalists are questioners and not thinkers and I know it from experience that it is a lot easier to ask but far more difficult to answer. I grew up in an era when the Times of India was a newspaper everyone read. Dileep Padgaonkar (former editor of Times of India) may have joked when he said its editorship was the second most important job in the country, but when he held that office, his voice was definitely one of the most carefully heard in the country. The morning after Babri Masjid fell, P.V. Narasimha Rao, the then Prime Minister of India, gave only two interviews, the first was to Dileep and not surprisingly it made banner headlines not just in his newspaper but in every single newspaper in the country. The other interview was to me & it paled in comparison.

Yet in those early days long before the onset of private sector television, when current affairs was consigned to monthly VHS video magazine, Dileep went out of his way to encourage people like me. He was always willing to appear on programmes and lend dignity and gravitas to an otherwise amateur and even jejune production. His presence lifted them and gave us credibility.

Twenty years ago, television was a very different animal to the beast it has become. But I instinctively feel, Dileep would have shared the questions and issues I wish to raise and even if he did not agree with the answers I plan to offer, I think he would have listened attentively. It is in that spirit that I approached the subject that I have chosen for this evening, A critique of Indian television news".

Just over two years ago TV news was a government monopoly. We were all captive audience of Doordarshan. Today, there are nearly 400 dedicated news channels while several others that have daily news bulletins in their schedule, and I haven't included BBC, CNN, Al Jazeera, Channel News Asia in this reckoning. They would be there regardless of the Indian news miracle. As a result, it's not an exaggeration to claim that news on television is a popular programme. Even if the viewership at any one time does not suggest that, the two other factors clearly do-the enthusiasm of broadcasters for news and the willingness of advertisers to support it. One consequence of this is that we are as a nation better informed or at least we have the potential to be. I accept that it all depends on what you watch. But, the very profusion of news and its easy accessibility raises questions we would not have asked before. Some of these questions might seem heretical coming from a television news producer, others point towards debates and solutions the west has encountered but which we in India have yet to experience. But, in either case, they are questions that need to be asked. Today, I want to raise some of them to suggest hesitant answers.

What sort of news do we get from television?

It's pretty much immediate, we no longer have to wait for tomorrow's papers to find out what happened today television news channels can tell you within a minute. Some boast of even doing so faster, their news can be visual and it is usually highly illustrative. Television shows rather describes you feel as if you are witnessing for yourself and although I do not want to exaggerate in that sense, television news can be participatory. But, television news have two important limitations and beyond that, it has an inherent tendency to sensationalise. Let's tackle the latter first.

"Television needs the sort of wisdom that comes with age. It has in plenty, enthusiasm, dedication, tireless striving and ceaseless vigil. All of that is remarkable for an industry so young, let that not be the game set"

Television's inherent tendency to sensationalise

The screen shows only what the camera films the camera films only what the cameraman focuses upon. This is not merely a question of subjective choice, although it is certainly that as well, it is also a technical matter. The camera will film the visual it focuses on, excluding whatever is on either side of it. Thus, a succession of closeups of a fire or of dead bodies or of fallen trees could suggest an enormous blaze or a massacre or severe cyclonic destruction. That may be the case, but it's also possible that may not. Yet in either event, the mind of the viewer will leap to this conclusion, the danger is it could be the wrong one. This is what I call television's inherent tendency to sensationalise. This is also why the statement, has to be true because I-saw-it-on-the box is actually misleading or at least it's based upon a fallacious understanding of television. But this problem is easily taken care of either by pulling out and showing wide shots that put events in perspective or by wisely written commentary. The only thing is when journalists are up against tight deadlines, which by the way is more often than not the case, such balancing is unfortunately frequently squeezed out.

The two limitations of television news are unfortunately more difficult to tackle and in India, at least I have seen so far very little attempts to tackle them. At times, there is even very little acknowledgement of them. The first limitation is that TV has problems handling what it cannot show. An anchor's head talking is not easy to follow because aural (not oral) information is the most difficult to comprehend, particularly when it is detailed, and graphics or photographs honestly do not always help. This is why television news bulletins occasionally ignore what they cannot film. In a western democracy where the reach of TV cameras is enormous, this has minimal impact. In India where the country is enormous and the reach of TV cameras is a lot less, the impact is considerably greater. This is why there is so much news in the newspapers than there is on television. Until social media came to our rescue, we could hear or read about lynchings but we never saw them.

Not so long ago I am sure many of you will remember, when the ABVP would ban jeans in Lucknow colleges, it would be an item in a newspaper but rarely a story on television. And the answer is simple because there was nothing to show. More importantly, this is also why the budget is so boring on television. First, it's just a speech, but then there's the question, what is the speech about? That in a sense is an even bigger problem. What it's about is not the price of commodities, not even the tax on the price of commodities, but the change in tax on the price of commodities and sometimes the percentage change in that tax. None of that is easy to visualise, so instead, we are shown potatoes and tomatoes. No wonder those who follow the budget on screen usually doze off.

"More than any other profession, journalism can draw hope from the fact, tomorrow is another day"

TV has a bias against understanding

The second limitation of television news I would say is more serious. I have to quote a phrase made famous in Britain by John Burt, a former Director General of BBC, in the 1970s, TV has what he called a bias against understanding. Let me explain and to do so, I will deliberately use a contentious desi example. When television tells you about a gruesome event like the murder of Graham Staines, it brings home the horror of what happened, as no other medium can. It sickens you, it tugs at your emotions, it stabs at your conscience and one of that is very welcome. But what television does not do is to explain why this happened. I don't mean who did it, how, where, when and of what time, those facts are easily communicated. I mean why how could followers of one of the world's most peaceful religions turn upon a single man and his two children. How could we people who think of ourselves as tolerant, welcoming and loving, kill so ruthlessly and mercilessly? Those are questions , of context, of background, of history. In the Graham Staines case, they were answered if at all they were by a judicial commission. No doubt newspapers don't tackle them adequately either, although in the opned pages they try but then newspapers don't make the same impact when they report such tragedies. Television does worse that impact pushes people towards easy conclusions and a rush to judgement follows. Two consequences standout we all think we know the truth behind Graham Staines grisly death and the guilty party feels hard done by. But the truth is embedded in a context television does not and did not explore and therefore most of us has not found about and the guilty party may well be guilty but we have not yet fully understood its guilt. This is why there is a bias against understanding inherent, particularly when television has to handle complex, complicated, not easy to explain stories, where the context is so critical to understand what has happened.

Let me at this point pause and sum up. Inadequate appreciation of the limitations of television and its inherent tendency to sensationalise, coupled with the fact that news on television is both more frequent and accessible, and often has greater impact, can lead to untended distortions or imperfect understanding. In such circumstances, news and views become perilously mixed up. Now so far I have spoken of problems intrinsic to the nature of television, alas in India we also have few that are a result of how we use this media. I shall now turn to faults that lie not in our stars, but in ourselves.

"We need the cold analysis of the current affairs, instead we have the spectacle and tamasha of clashing viewpoints. We need to shed light but we end up generating heat"

"We fail to speak truth to power, but also we treat viewers like dumb animals who cannot see through the tricks and will not demand better"

Faults that lie not in our stars, but in ourselves

As someone who has spent over 35 years in television, I'm particularly perturbed by four trends I've repeatedly noticed in the last few years. After a recent break from television, I feel a moral compunction to speak. Not to do so would do let down the profession I love. First, there's the way anchors choose to interview the Prime Minister. It's done with an obvious difference, which leaves little opportunity to challenge or even cross-question. Instead of focusing on well-researched subjects, which are then pursued with diligence, each question changes the issue, there's no follow-up. Consequently, a multitude of subjects are raised without any meaningful achievement. Equally importantly, the Prime Minister is permitted to answer at exorbitant length, often rambling and frequently changing the subject and getting away with it. And let me be honest, even Donald Trump has never been interviewed in this way. Worst still is the character of the questions put to the Prime Minister, not only are awkward issues avoided, but the questions are emolliently phrased and very gently asked. Instead of bringing up lapses or misjudgements, the Prime Minister is instead asked to hold forth on the opposition's alleged errors. At no point is he questioned about things that have gone wrong under his job. The end result is the interview lacks rigour. It feels like an easy ride and frankly, it's the same, whether you watch it on CNN-News 18, Times Now, Zee or India Today.

A second concern is the way some anchors behave during television discussions. Those guests who represent viewpoints they agree with are treated gently, permitted to speak frequently and at whatever length they want. But, the guest whose views are contrary to the anchors, he or she is treated like a guilty prisoner in the dock. Voices rise, language loses its restraint and questions are fired relentlessly. The tone is accusatory and a deliberate attempt is made to shame the person. He or she is frequently interrupted, indeed they are given a little chance to answer one question before the next is hurled at them. Yet the object of a discussion is to give the audience a chance to hear different viewpoints articulated by different voices. The aim is to explore artfully and forensically and leave the audience both enriched and able to judge for itself. Where fair and even-handed treatment is required, the anchor instead takes sides and each time he does that, he or she exposes his or her prejudice. Frankly, this can only diminish the anchor. You see this sort of discussion most often on Republic TV and Times Now. But there are younger anchors on other channels, who have also fallen prey to this practice, presumably because they think it wins audiences and perhaps easy popularity.

My third concern is best reflected by NDTV because it seems to be the only English news channels with a credible prime evening news broadcast. Frequently after the story, the newsreader feels an urge to tell the viewer, what to think and how to judge its content. Now those remarks by the anchor might be piffy but they still are editorialised. It's the newspaper equivalent of a comment by the editor, at the end of every front-page story, telling the reader to make something of what he's just read. Frankly, this breached what I would consider the sanctity of news. The viewer should be told of what's happened, not how to judge or what to make of it. The latter is an intrusion of the news reader's personal viewpoint, which is always unnecessary and frequently unwelcome. Worse, this ends up treating viewers like children, it's therefore also demeaning because it's infantilising. NDTV is a channel I respect and have the least complaints about, yet this is a problem that rankles almost every single evil. I'm surprised the channels' editors have allowed it to continue.

The grotesquely nationalist hashtags TV channels now seek to push a story or gather a response is my fourth concern. These hashtag are like drumbeats designed to marshal or dragoon the desired response. They deny you an opportunity to think for yourself, instead they seek to corral your thoughts, worse, they are artless and crude and in fact affront to intelligence. Here is an example, "Fight for India", "Love my Flag", "Proud Indian", and as we used to see, "Anti-nation JNU". These are crude immature attempts to play with our emotions. These are signs that we the viewer are being treated like children, who need to be pushed in a direction, told what to think and if we're still reluctant, it's actually imposed upon us through these hashtags that condition our response.

Quest for the truth has to be unchanged

Finally, the argument that I have criticised is an illustration of new age journalism carries no conviction with me. I may be old fashioned, but even if a story presented may alter with time and technology, its quest for the truth has to be unchanged. No matter how a story is delivered, good journalism, if it's there, will stand out. Bad journalism on the other hand cannot be disguised, live aside forgiven by self-serving excuses about the mode of the people or the atmosphere of our time. And certainly, no attempt to make journalism popular, justifies lowering standards of objectivity or the critical requirement of fair play. Ultimately, this is more than just about news channels, indeed it even goes further than our democracy. It's about us and how we receive the unvarnished truth. If we tolerate half-truths and misrepresentations, we are only ourselves to blame. Most of the people I know, believe the media frequently gives them half-truths and misrepresentations. And this brings me to the question, what would the greats of Indian journalism, the Frank Moraes, the Girilal Jains, the Prem Bhatias, George Vergheses, the Kuldip Nayars, have made of Indian journalism today? Would they applaud their successors or would they cringe with despair, would they feel the flower has brightened and blossomed or would they sense that it's starting to shrivel up and even rot? The answer lies perhaps in two great changes that have occurred since the 60s, 70s and 80s, which are the decades when Moraes, Jian, Bhatia, Verghese and Nayar were the doyens of journalism.

"Television news needs to supplement reports of what's happened with analysis of why and what it means. In other words, news analysis has to become part of news reportage"

The reputation that media once enjoyed

First the reputation that media enjoyed for reliability, balance and accuracy has grievously suffered. Today you often hear the put-down, just because it's in a newspaper on time or in television, doesn't mean it's true. Social media may have spawned fake news, but the fact that people rely on Twitter or WhatsApp or Facebook to find out what's happened, suggest they no longer trust a newspaper or news channels to tell the truth or the full story. Connected to this is the claim that media could once make of being objective and fair fewer people are prepared to believe that today. Without double checking or giving a person the right to reply and often without knowing the full story, the media judges individuals and finds faults with them. I don't deny there are occasions when we are right, but every time we are wrong, we condemn an innocent person and leave him with little opportunity to correct the prejudiced image we have created.

The truth is whatever you make of the promise of Achhe Din, these are not good times for the Indian media. Most people I know have formed an irrevocable impression that the Indian media has become pusillanimous. Where once newspapers and television channels boasted of challenging and exposing the government, we now flinch from doing so. Worse, when our voices are raised, it's against the government's opponents and critics. Particularly, those who have the gall to question the Prime Minister or the Army Chief. Instead of watchdogs that should growl at the authorities, even if occasionally, mistakenly, the media behaves like guard dogs who want to protect, or pet dogs who just want to be liked.

The saddest part of all of this is that the electronic media of which I'm a part, which is widely thought to be most to blame, whether it's our interviews with the Prime Minister, where we refuse to challenge and sometimes even to seriously question; or our panel discussions where volume and heat are deliberately preferred to substance and light; or the crude hashtags we deploy on-screen, which are drumbeats designed to marshal or dragoon the desired response. The net result is we fail to speak truth to power, but also we treat viewers like dumb animals who cannot see through the tricks and will not demand better. We've even reached the stage where the Chief Justice of India in an open court has had to admonish the electronic media. And instead of standing up in our defence, newspaper editorials have agreed with them.

This is what the Business Standard had to say last year - There is little doubt that the abandonment of fact checking and of even a pretence to fairness by the electronic media, have put into jeopardy not just freedom of speech but also the smooth working of democracy itself". Of course, television as we know it today did not exist when Moraes, Jian, Bhatia, Verghese and Nayar presided over Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg. In their time Doordarshan was the placing of rulers and rightly provide. As I said earlier, we have nearly 400 independent news channels, and they might perhaps be flabbergasted at the sheer number. But, if those five great journalists of the past were to ask a simple question, I wonder how many channels stand up to that critical test. Is there a channel that India can be truly proud of just as the British are justifiably proud of the BBC or the Americans of CNN? I am really not sure what their answer would be and to be honest, I'm even scared to find out yours.

Is there a channel that India can be truly proud of?

Let me share my own answer, there are some channels I am proud of some of the time. Some programmes I am proud of most of the time. But there are also a few channels and programmes that make me cringe all the time. Whilst there are newspapers that I would unreservedly applaud, I'm afraid there isn't a single channel I can say that of without biting my tongue because I know what I am feeling. But this is not the hopeless situation it might seem.

"The fact that people rely on Twitter or WhatsApp or Facebook to find out what's happened, suggest they no longer trust a newspaper or news channels to tell the truth or the full story"

Tomorrow is another day

I know I have painted a pretty black picture, but there is a possibility of sunshine breaking through this darkness. After all, the media changes every day each edition of a newspaper and each bulletin of a news channel, is a chance to begin afresh. A new reporter, a different anchor, a better editor and everything could change very quickly. Perhaps more than any other profession, journalism can draw hope from the fact, tomorrow is another day.

So, what's the solution, I promised hesitant answers and hesitantly I shall attempt them. The first lesson is that reportage is not enough, we need more context, more explanation, more background. In turn that means, we need more specialist correspondents, more correspondents with dedicated fields to furrow and fewer firefighters. It also means that for most important developments, television news needs to supplement reports of what's happened with analysis of why and what it means. In other words, news analysis has to become part of news reportage.

The second lesson is that we need more current affairs. News on its own is not enough, we need programmes that go deeper, wider and further. I know that in India, at least in theory we have them, but they fail to serve their purpose. And I include my own in that judgement that unreservedly such programmes work, such current affairs programmes work, when they take their subject more seriously than the personalities participating in them. In India, it's the other way around. We need the cold analysis of the current affairs, instead we have the spectacle and tamasha of clashing viewpoints. We need to shed light but we end up generating heat.

Finally, television needs the sort of wisdom that comes with age. It has in plenty, enthusiasm, dedication, tireless striving and ceaseless vigil. All of that is remarkable for an industry so young, let that not be the game set. But, it does not have the capacity to reflect, to pronounce wisely, to be sagacious, to speak with gravitas. No doubt such qualities are difficult to acquire, but their absence is telling. Of course there is a lot more that can be and should be done, but my intention is to raise questions, focus attention and hopefully start a debate. For that purpose, I think I have said enough.

Disclaimer : The opinion expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of Corporate Citizen and Corporate Citizen does not assume any responsibility of liability for the same