They say matches are made in heaven. But sometimes they are also made in the Officers’ Mess of the IAF, as was Wing Commander Anupama Joshi’s and Wing Commander Ashok Shetty’s, who first met at the Baroda Air Force station. How did it all happen? Hear it from this inspiring couple who, together with blossoming their romance, fought and won their fight for gender equality in the armed forces

“We were on a night formation mission and I was in the fourth aircraft, the second and third went down in front of me. To land back safely to base was our first concern. To fly under that pressure is what military flying is all about. That is what you learn in the forces— performing under pressure!”

stories in movies but real life is a lot more complicated, more so in the Air Force (AF). Yet men and women in blue do fall in love, as did Anupama and Ashok.

Anupama: Those days there was only one phone at the Mess reception. Once I saw four glasses of whiskey lined up there, so I presumed there were other officers queued up for the call. I kept waiting when I saw this tall, dark and handsome man approach. I nervously asked him, “Sir, are you in a queue behind this?” He proudly proclaimed that all four glasses were his, and he had lined them up as the bar had closed. That broke the ice as he generously offered me any help I required, as I was new to the place. Ashok: I could see how alienated she was in the group since male officers didn’t interact much with her. I offered to help if she needed to go out to the city since I had a bike. I included her in my group of friends and slowly we started having meals together, spending time together and came closer to each other.

Anupama: At that time Ashok was a transport pilot at Jorhat in Assam where he had injured his knee playing basketball. Till the time he was medically fit, they had sent him on a missile course in Baroda. After the initial hiccups, we became friends and found that we had plenty in common. He started taking me out for dinners, movies and to play squash in the nearby ONGC sports club. One day he introduced his friend’s wife, a journalist and a JNU-ite, so I could have some company. That was indeed a great relief. Slowly we formed a group and began to meet more often.

“I could see how alienated she was in the group since male officers didn’t interact much with her. I offered to help if she needed to go out to the city since I had a bike. I included her in my group of friends and slowly we started having meals together, spending time together and came closer to each other”

Anupama: When his course was coming to an end, he realised he wanted to be with me. The day he was to leave with his friends for Jorhat by night train, he came to my room and confessed his feelings. Though I had sensed it, I was taken aback. I said, if you really want to prove your love, go to Jorhat tomorrow. I knew they had great plans for the journey with food, daru and stuff like that. Around 8 pm, the whole gang left and at 8:30, he knocked at my door again (laughs). Actually, I put him through multiple tests to make sure it wasn’t just an infatuation and that he was serious about it. One such test even cost him his promotion. He had to appear for an examination, but just a day before that he told his boss, took a flight and came to meet me late at night in Delhi from Jorhat to assuage my feelings. I was stunned. By missing this examination, he got his promotion a year later. That was the time I realised he was really serious about this relationship.

Anupama: Surprisingly, our parents were very supportive. There was no twist in the story—no North-South divide. Though my in-laws belong to the Bunt community of Karnataka, they didn’t object to their son marrying a Brahmin girl from the North. With such overwhelming support, we got married in February 1994.

Ashok: My dad was cool; my mom was also not perturbed. My parents are from the South (Mangalore) but I was born in Guwahati and raised in North India. I joined NDA and went to the Air Force. When I went to Anupama’s house, her father was also fairly cool. Contrary to the story she had been telling me about them, they were pretty nice and open about it.

Just before I hung up my uniform

Just before I hung up my uniformAnupama: Post-marriage, Ashok got posted to Rajpura, near Chandigarh, while I was still in Baroda. So, initially, it was a long-distance marriage and a major part of our salaries would go for telephone and train bills.

Once Ashok came to Baroda on leave where we met Air Marshal KC Cariappa, son of Field Marshal KM Cariappa, at dinner. When he learnt that Ashok was waiting for his posting, he made sure that he was soon back to flying with a new posting at Agra. After some time I got transferred to Agra where we spent considerable time together and also had our son, Agastya, now 20, and currently in Canada for his commercial pilot license.

We then got posted to Sulur near Coimbatore, then to Hyderabad where I was at Hakimpet and Ashok, 25 km away, at Begumpet. He was posted back to Baroda while I was still in Hyderabad. A year later I also joined him at Baroda—which turned out to be the place where I began and ended my AF career.

Ashok: Nobody wanted to take a decision. Initially, senior officers were very particular about women. They were scared that if something happened, their necks would be on the line. Nobody seemed to be against her, but at the level of the MoD and Air Headquarters, things were hotting up. For a decision of this magnitude, there should have been a thought process which wasn’t there. The induction process itself wasn’t thought out well. Air Marshal NC Suri decided in favour of women’s entry into the AF and went ahead with it. But the forces weren’t ready for it. So, she would send her applications but they wouldn't touch it, thinking, let it be someone else’s baby.

Complete family, including An-32

Complete family, including An-32She’s very, very clear in her ideas. My thinking is pretty muddled up. She knows what’s right, what’s wrong and what’s to be done and how. So, I keep quiet. No ego issues due to my being a man. However, if there is some issue related to my work, I don’t take her advice.

Ashok: It’s physics! Opposites attract (laughs).

Ashok: You need to be flexible. That’s the sole mantra. There are times when you need to accept that you may be wrong.

Anupama: It’s a give-and-take relationship. You need to appreciate what the other person may be doing for you. I really value that he stood by me throughout my struggle. If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have stayed on course for so long. I know how difficult it is to take on an organisation, but he took that risk and showed his mettle.

My parents have had a huge impact on my life, so much so that I chose a profession in the air after them. They’ve always taught me to be driven and composed, assertive yet humble and they themselves embody these virtues flawlessly. Both are of strong character but interestingly different personalities. Growing up, I didn’t really understand this but now when I see, I find my mother the dynamic achiever, who’ll stop at nothing to right a wrong, and my father the calm, level-headed man with a brilliant head on his shoulders. The two may seemingly be different but together as a team, a unit, a couple, unparalleled. I’ve always been in awe of them and I know I will always be.

About to be married

About to be marriedAnupama: It’s a welcome change but it’s sad that people don’t realise that women have been there for 26 years. The onus is now on women to make their mark and not let the whole applecart turn.

I would have, if I had not committed to this startup because my heart belonged to the AF. But they had invested huge money in Uttarakhand where I had set up this branch. I decided not to join back because my fight wasn’t for myself—it was for a cause which I had won.

Extremely challenging—this was after I did my course at IIM Ahmedabad. There is an Institute of Financial Management and Research in Chennai. They opened an IFMR Trust incubating rural banks. The entire team, comprising ICICI bankers, was inspired by the Bangladeshi model. They thought that military officers would have more credibility. So, I was picked to head the Uttarakhand entity. I spent seven months with them in a Thanjavur village to understand the whole model and replicate it in Uttarakhand.

The biggest challenge was to win the trust of the hill people. I visited 600 villages on foot. Another challenge was, how to make rural women understand the value of banking. Being from Uttarakhand helped. They could relate to me completely.

Very successfully. The first branch began in 2009, now there are 25 branches with 250 people. Close to 100 crore have been disbursed.

Ashok was posted in Varanasi and my son was in Class V. I had to frequently visit remote villages and my health was also deteriorating. When I went to Doon School for my son’s admission, I had apprehensions about boarding school. When I spoke to the headmaster, I told him I was planning to take a sabbatical. He suggested I join the school for some time and see. It wasn’t out of design, it just happened.

I’m director of personnel there. Doon is also registered as a company, which takes care of the legal and compliance parts for Doon School, and I’m involved there too.

Anupama: He left the AF in 2012. Initially, he was on loan to the Uttarakhand government as a pilot for two years. Currently, he’s head of operations (flying) and the Chief Pilot. He flies the CM and the Governor.

Ashok: I’m the quintessential fauji. I believe that the organisation is always right and our aims are subservient. The requirement of the organisation should always be placed ahead of the individual.

Life may not always give you what you want but that’s no reason to be disheartened. Learn to be happy with what you’ve managed to accomplish. That’s the mantra to a satisfied life.

Ashok: There isn’t anything special required to join the AF. It offers an unmatched life. Things have changed in the past 30 years and made AF ideal— by and far. With pay commissions coming in, salaries are much better. The machines we have today are among the best in the world. Life is brilliant. So I would encourage youngsters to join it.

Stranger to the ground

Stranger to the groundIn the civilian set-up, they don’t bother about operational requirements. My AF training has given me a very professional outlook on how to manage aviation. Rules and regulations are very specific in aviation. In the armed forces, we have leeway for damage but in the civilian set-up, that’s not acceptable.

In Kargil, I flew extensively to Kashmir.

I was always good in sports and not much interested in studies. During my 12th I realised that with my physical capabilities, I would probably do well in the armed forces. I appeared for the NDA entrance exam, cleared it, and cleared the SSB interview at Varanasi. Before I knew it, I was in the awe-inspiring campus of the famed NDA in Pune.

NDA was tough physically, and contrary to my belief, there was emphasis on studies! NDA builds a bond between course-mates which survives forever. Later in life the first question on meeting another officer is always: “Ex- NDA?... which squadron, which course?”

I loved my time in the IAF. There were times of pain and sorrow when we lost brother officers in aircraft crashes or road accidents, but the benefit of living each day in the group of officers in the squadron ensured that we bounced back to face another day.

My first posting was in an AN-32 squadron whose primary task was to maintain logistic connection to the Ladakh region including the Siachen glacier. Paradropping of supplies at the isolated army posts in the desolate crevasse-ridden glacier is a challenging task because the aircraft is flown at the limits of its capability with no margin for errors. Later I served in the Paratroopers Training School and also in a squadron which maintained connectivity with the Andaman and Nicobar islands. I served in Jorhat and in Vadodara. My time with the IAF took me to each corner of our great country. I enjoyed the experience!

I vividly remember a 1991-incident involving a mid-air collision. We were on a night formation mission and I was in the fourth aircraft, the second and third went down in front of me. To land back safely to base was our first concern. To fly under that pressure is what military flying is all about. That is what you learn in the forces—performing under pressure! Just a week back, we lost our friends in another AN-32 crash. The squadron had lost a dozen men, but it was up and flying and doing its routine high-altitude air maintenance of Ladakh.

Three lessons which corporates might find useful are: a) Top-down leadership is essential for the organisation to stay on track. A good leader has no problem in leading his band to achieve the impossible. b) Incorrect decisions by a leader must be questioned by the organisation; and c) In any organisation the top management must always feel the pulse of the junior-most personnel.

Most definitely a strength. Anupama was on ground duties, holding important portfolios. Since I used to be on flights, she would look after all of my admin-related work. In turn, I would be her pointsman when she needed something from other AF stations.

All responsibilities were shared between us though I must admit, compared to me, she did a much better job. Her focus on him was unwavering despite all the load of office work. I would be flying in and-out all the time and would pitch in when I could.

After father and son landed in Gimli, Canada

After father and son landed in Gimli, CanadaThe change is welcome. What matters is efficiency, not gender. The armed forces need good soldiers irrespective of whether they are male or female.

It would help if the armed forces visited schools more frequently and motivated children to join it.

I am looking after flying operations of the civil aviation department, Govt. of Uttarakhand. Compared to the scale of operations in the IAF, this is a piece of cake. What is difficult is getting used to the civilian way of working.

I was involved in the Kedarnath disaster rescue mission in 2013. The civil set-up was not geared up for disaster management. It was a mammoth operation executed by the Air Force with the added pressure of almost live TV coverage.

My role is to provide basic means—education, accommodation, etc. Thereafter, Agastya has to chart his own course. He has seen me in this field and got interested in flying.

In 1992, the first glass ceiling in the Indian armed forces was shattered when 12 women got inducted into the Indian Air Force, Wing Commander Anupama Joshi being one of them. But what followed in a rigorous and rewarding career was a long battle for equal opportunity for women, which she finally won in 2010, after she had retired from service and moved on to other pursuits. But not before she paved the way for a long line of women to follow and touch the skies...

Two years ago when the Indian Air Force (IAF) inducted the first batch of three women jet fighter pilots, they said the IAF shattered the ultimate glass ceiling for women. But not many know that the IAF had opened its doors to women in 1992, initially for ground duties and later for flying transport aircraft and helicopters as well. But equal opportunity for career growth was still a distant dream. Wing Commander Anupama Joshi, from the first batch of 12 women officers who joined the IAF, was denied permanent commission because of her gender. Result: After exhausting all her in-house options, she took her fight to the court. It took her seven years to win this battle. But when in 2010 women were given the same opportunities as men in the defence forces, she had retired in 2008. But she made sure that successive generations of women could truly live up to the IAF motto of ‘Nabham Sparsham Deeptam’—touch the sky with glory.

She personified courage, passion and leadership, and despite shaping the course of history for women, she didn’t rejoin the IAF when she was reinstated. She chose to take up another challenging task, becoming the founder-CEO of a microfinance startup working for the financial inclusion of women entrepreneurs in the remotest parts of Uttarakhand. Currently, she is Director of Personnel at the prestigious Doon School.

Winner of several awards from the Uttarakhand government, this brave leader shared her career journey with Corporate Citizen: Over to Wing Commander Anupama Joshi, in a first-person interview:

“I was born in Betul (Madhya Pradesh). My father was from the Indian Forest Services. Since his was a transferable job, I studied at different places in Madhya Pradesh and later in Bhutan and Himachal Pradesh where my father went on deputation. I did my graduation from Shimla in Arts, with Economics and Psychology. I did my M Phil from JNU’s School of Social Sciences, Delhi.

Twenty-five years ago JNU ranked No. 1. Its atmosphere was intellectually stimulating and transforming. Everybody aspired either for the IAS or politics or pure academics. I too experienced those currents which taught me to question things. However, since my father was a civil servant, I began thinking about joining the services.

While doing my M Phil, I saw an advertisement in India Today which said, ‘Be a Pioneer’. The military was, for the first time, opening its doors to women. Though I was doing research, I was also into sports and pretty active. I got very excited, applied for it, appeared in the SSB and the rest, as they say, is history.

My service selection board was at Dehradun. I found lots of girls there whose parents were army officers. It was very evident that they had been coached. They knew the military jargon. I wondered where I was. They do an aptitude test on day one. If you pass it, you continue for the next five days, otherwise you’re sent back home the same day. Well, I made it!

There was also media buzz that over a lakh applications had been received, 25,000 were short-listed and the doors were open for 12 girls.

After a medical at Delhi’s Subroto Park, I joined the Air Force Academy (AFA), Hyderabad. 2018 is the silver jubilee year of our passing-out as we got inducted in 1992 for the oneyear training.

Although at Hyderabad the training is the same for men and women, when we went, the Academy was not prepared for us. Since we were the first batch, they didn’t know how to deal with women. For the first 15 days, we didn’t even have a uniform. The Air Force (AF) was still undecided about it. We attended classes and walked around in coloured clothes—much to the envy of our male colleagues.

Soon, we were given the same uniform. The adrenaline rush and the pride you got when you don a uniform was phenomenal! We had a gruelling schedule at AFA where the day started with a run and before you knew it, you’d be on parade, cross-country, weapons training, jungle camp in the middle of the night and what not!

With Ela Bhatt, role model in my second avatar

With Ela Bhatt, role model in my second avatarI won’t say that one year at the academy was easy because one, it was rigorous and two, lots of conflicting things were happening because we were new to the system and the system was new to us. It was like a difficult marriage.

We didn’t have any seniors because our seniors were all males and the poor guys were told not to mess around with us.

When juniors come, seniors take the onus of responsibility of getting them into the system. It’s not ragging, but ‘indoctrination into the military’. They give what’s called ragdaa to help juniors get into the system.

The process was a bit of a struggle for me initially: not physically but mentally. Coming from a freethinking and questioning JNU milieu, it was very, very challenging. You wanted to question many things but couldn’t.

Once, I was walking down the corridor, it wasn’t even a month in the Academy when a Drill Ustaad called me, “Come here.” I looked at him and said, “Please don’t point those fingers at me,” because in JNU you just couldn’t do that. That guy must have felt, ‘how dare this cheeky woman question me’, but couldn’t do anything as he wasn’t sure what punishment he could give me. Had it been a male cadet, he would have surely ordered, “Start rolling.”

In two months, everything changed: we were awarded the same punishments that were given to male cadets. But we also realised these were meant only to make us robust and mentally tough.

I remember they have something called a Patti Parade where they call us and say, “Go and change into your uniform in five minutes and come back.” You run, change into uniform, come and they look at the time. If even one person was late, the whole group would be punished. We also learnt that the whole essence of the military was: Follow the command. If your commanding officer says, ‘Line pe jaake lado,’ and you question him, what will happen? (laughs)

We were issued a bicycle each to reach the Academy from our Mess. We had to pedal it out but not allowed to cycle carrying another person. Once my cycle got punctured and while I was hitching behind my friend’s cycle, we were caught. Result: Adha raasta vo cycle upar rakh ke dauda aur aadha raasta main. They made sure that we were treated equally.

“When we went, the Academy was not prepared for us. Since we were the first batch, they didn’t know how to deal with women. For the first 15 days, we didn’t even have a uniform. The Air Force (AF) was still undecided about it. We attended classes and walked around in coloured clothes—much to the envy of our male colleagues”

“I won’t say that one year at the academy was easy because one, it was rigorous and two, lots of conflicting things were happening because we were new to the system and the system was new to us. It was like a difficult marriage”

With the President and Prime Minister. The pioneers

With the President and Prime Minister. The pioneers1992, the year we got inducted was the diamond jubilee year of the IAF. We were ‘showcased’ during the AF Day Parade. Right from the President Dr Shankar Dayal Sharma, Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao, Defence Minister Sharad Pawar and Leader of the Opposition, LK Advani—all attended it.

Generally in a year of training, cadets never leave the Academy, but they made an exception for us and we were flown to Delhi from Hyderabad. It was like a film being shot as I led the marching contingent. We then had tea with the President and the Chief, Nirmal Chandra Suri, introducing us said, “These are my 12 angels.”

It was a heady time. We did the 25-km cross-country and the night-long jungle march, with just a bottle and rifle. In the pitch darkness, a lady cadet lost a rifle component. You couldn’t return until you found it. Initially that seemed impossible, but by early morning we found it!

Incidentally, I was a good swimmer while the other girls didn’t know how to swim. I once participated in a swimming competition with the men, but when I jumped into the pool, all the 11 girls forgot their respective squadrons and cheered for me!

All the firsts!

All the firsts!We got commissioned on June 21, 1993 and my first posting was at Baroda. My office was the erstwhile palace of the Maharaja of Baroda. It was beautiful. Donning my blues with pride and glory, I walked down the corridor of the officers’ mess and asked the person in-charge for the room-keys for Pilot Officer Anupama Joshi’s room. He looked at me very quizzically and asked, “Sahib kahan hain?” I cannot describe the incredulous look on his face when I told him, “Main hi sahib hun.” The first few days were difficult. Everybody looked at you strangely. You were the only woman there.

Once I faced an incident of insubordination, which is mostly unheard- of in a military academy. A man placed under me refused to take orders. When I complained, it was I who was counselled, saying that the man in question belonged to a state where he was socially engineered not to take orders from women.

This and many such incidents made me realise that though the opportunity was given, there were barriers that needed to be broken and mindsets that needed to be changed.

Twenty years back the ground reality was, you were watched all the time. Seniors wouldn’t know how to treat you. Your colleagues would be sitting in a dining hall bustling with laughter and energy, but the moment you walked in there would be pin-drop silence. They didn’t know how to socially react to a female officer. Every minute and every time you were treated more as a woman, less as an officer.

I had joined the Education Branch but you do get to work in different roles — being in-charge of the Mess, looking after food and rations, or as a fire officer or security officer or administrator of the camps. I assayed all these roles. Later, I also taught. I was in the fighter training wing of Hyderabad’s Hakimpet station. I also worked in the navigation training school and taught AF subjects like Defence History and AF Laws to young officers. Once I looked after the married accommodation of the entire AF station with 3,000 officers. But sometimes you get strange reactions too, like when I became the Security Officer, everybody said, “How can a woman do it,” but my boss thought I’d do a better job than the rest.

“Your colleagues would be sitting in a dining hall bustling with laughter and energy, but the moment you walked in there would be pin-drop silence. They didn’t know how to socially react to a female officer. Every minute and every time you were treated more as a woman, less as an officer”

A break between

an operation!

A break between

an operation!Today AF takes pride that it has broken the mental barrier to accept women in combat roles. But it took them more than 20 years to actually do it, but there was a long-drawn history of legal battle and that’s where my story begins.

When the euphoria of induction was over, the reality hit us. When it came to courses, promotions, postings, placements—we were not entitled.

Initially, they had taken us in for five years “on an experimental basis”. But when we were in the fourth year, they didn’t tell us what would happen after the fifth year. By then I was married. Everybody had got settled. We obviously wanted to continue further.

I wrote an application asking for a permanent place like our male counterparts. Nothing happened for seven months, but when we were about to complete the fifth year, we got the news that our services were extended for four years.

All of us felt very happy and started breathing easy. But what after four years? Why this ad hocism? Over a period of time, we started realising that there were lots of opportunities we didn’t get because we were from the SSC. There were constant battles.

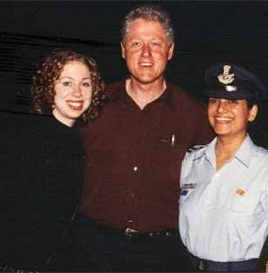

Receiving the President of US Bill Clinton and his daughter Chelsea on their visit to Agra

Receiving the President of US Bill Clinton and his daughter Chelsea on their visit to AgraI remember applying for a junior commander’s course. It’s mandatory if you want to attend the prestigious Defence Services Staff College at Wellington, near Ooty. My application was rejected because short-service women were not eligible for in-service courses. But short-service men were, a prerequisite for career growth in the services, as they had the option to continue.

I was enraged. I argued—I did not opt not to serve. You give me permanent commission, and let me do the course. But they didn’t listen. Then I acted a little smart and sent my name again but as Ft Lt A Joshi, and voila! I found myself in Red Fields, where the course was conducted. My husband also opted for the course, so we did it together. I finished it and this opened up opportunities for the rest.

Then we got posted to Sulur in Coimbatore I put in my third application, as I wanted to stop this ad hocism. When an application is given, it goes to the higher command and my commanding officer’s remark always was: “She’s a professional and an asset to the organisation.”

One year passed, nothing happened. Meanwhile, my struggle to be treated equally continued even in small things like night duty. Once a month, as Duty Officer, you do night duty on rotation but women were exempted. I felt when I got the same salary, same facilities, why should I not do it? One day, as Adjutant of the unit, I detailed my own self to do it. Some women resisted, saying why are you unnecessarily doing it when it’s not required? But I felt, when you’re a pioneer, you’ve got to set certain things by example.

As we were close to the end of our second tenure, I made a representation again. I didn’t hear anything for long. Then I was told it was a matter of the tri-services, also involving the Army and the Navy and the matter was pending with the Ministry of Defence (MoD).

A year passed, there was no reply. I requested for an interview with the Chief of Staff, Air Marshal S Krishnaswamy. With great difficulty, I met him and he said the same thing: “Anupama, wait, the matter is with the MoD.” Wait I did.

Another year passed. I put in my next application. By then, the Chief had changed. The new Chief was SP Tyagi. Though I didn’t get any reply, we got six years’ service extension.

I wasn’t happy with this ad hocism. I wanted an answer to my questions: Why couldn’t we get a permanent place? Why couldn’t we continue our tenure? Why didn’t we have the choice to serve the country which was our constitutional right? Why were there double standards in SSC for men and women? Why could men get permanent commission but women couldn’t?

Rare work-time together

Rare work-time togetherMy argument was: If I get the best of the scores in my annual reports, how can you deny me permanent commission and give it to men whose ratings are much below mine?

I put up yet another application. This time to the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces—the President of India. By then I had sent six applications and six years had already gone by.

I put up an RTI, but that was stonewalled. They said matters of human resources and establishment in the military were of national importance and hence didn’t fall under the ambit of RTI.

What was I left to do except knock at the doors of the court?

By then a large number of women had also joined the IAF. I contacted almost 60 of them so as to have a collective representation—it could become a class case. Sadly, only one came forward—Sqn Ldr Rukhsana—who believed in me to fight this legal battle jointly.

We went to the Delhi High Court with a very simple prayer: that we be given a permanent place in the IAF on the basis of our efficiency and not on the basis of gender.

It was a very daunting task for us. We were fighting against an organisation that was extremely structured, hierarchical and disciplined. While it was represented by eminent lawyer Gopal Subramanium, we didn’t have any big lawyer to represent us. We contacted all the great women’s rights lawyers—Kamini Jaiswal to Indira Jaising to (the late) Rani Jethmalani but they didn’t take our case. Seven years were spent in the corridors of the court, by then my tenure had ended and I was out of my blues. Not wavering from my goal to right such a gross injustice, we finally found our success in 2010 when the landmark judgement came: women must also be given a permanent place in the armed forces!

‘In this battle of equal opportunities, the largest support came from the men. The men who inducted us, the superiors and colleagues who believed in us—all men.

The most important lesson was: You may have the courage, you may have the conviction, but in the end, it is perseverance that will prevail.”

Anupama yet again created history by being reinstated back into service which again was unprecedented in the armed forces.

By Pradeep Mathur