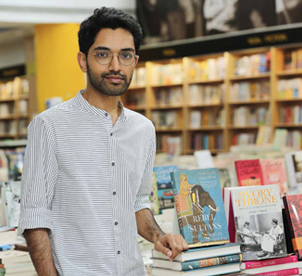

Manu S Pillai, the winner of 2017 Yuva Sahitya Akademi Award for his maiden non-fiction book `The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore’, is already being talked about as a formidable young historian, who is scripting unconventional history books through meticulous research and understanding of that relevant era. This is quite an unusual career trajectory, considering that he graduated in Economics with a post-graduate degree in International Relations. In a candid interview with Corporate Citizen, Pillai reveals his eventful journey down India’s historical memory lanes.

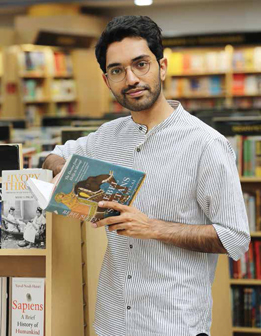

Manu S. Pillai, who is in his mid-twenties, was born in Kerala, educated at Fergusson College, Pune and at King's College London. Formerly chief of staff to Dr Shashi Tharoor in Delhi, he has also worked at the House of Lords with Lord Bilimoria, a crossbench peer, and with the BBC on their ‘Incarnations’ Indian history series, which tells the story of India through 50 great lives. He writes a weekly column for Mint Lounge, and his essays have also appeared in The Hindu, Hindustan Times, Open Magazine, Times of India, and so on. Written over six years and researched in three continents, his award-winning first book, The Ivory Throne, has now been followed to much acclaim by Rebel Sultans. Read on…

Manu Pillai: I was getting into a taxi to go watch a movie (I think it was Wonder Woman) when my mother called and demanded to know why I hadn't "told her". I had no clue what she was talking about. She then informed me that somewhere on television, when the awards were announced, my name had appeared. I carried on to watch the film and the call from the Sahitya Akademi came the following day. I was of course happy not only for the recognition, but also to join a list featuring some extremely bright Indian writers, across languages and regions.

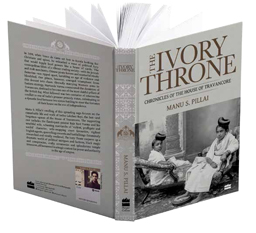

The book is a history of Kerala, told through the life of the last female Maharajah of Travancore, Sethu Lakshmi Bayi. The historical side of the book deals with a variety of themes—colonialism, the rise of a Hindu dynasty within that context, the matrilineal system of inheritance where women dominated, and the collapse of this order at the dawn of communism in Kerala. But the book is also a biography of Sethu Lakshmi Bayi. She was a remarkable woman who was made as queen at the age of five, started to rule in her late 20s, was pushed out of power in her late 30s, lost the kingdom completely upon Independence, in her 50s, and in her 60s she left the palace and that whole world behind, and moved to Bangalore where she died as a complete ‘nobody’ in the 1980s. There was drama, politics, intrigue, power- struggle, and much more in her life, and all this made for a riveting story to resurrect in public imagination.

When I first began to ask about her, it seemed she survived only in hushed voices and whispers—as if they did not want to tell her story. Although her name kept popping up, it was always in this footnoted way. She was never given the prominence she deserved, despite her exemplary work. So then I started doing some research on her but people kept telling me not to get into that story because lots of skeletons in the closet would stumble out, and so on. As an interested teenager, I was even more determined now to unearth her tale. I got in touch with her granddaughter who sent me a copy of all her private correspondence, diary entries and so on. We exchanged notes for nearly two years while I was reading her private papers. Then I went to London and collected some material from the British Archives. Subsequently, I located more material from the Delhi and Kerala state archives. Then again I was back in London, sourced some material from America. After six years of writing, finally in 2015 the book was done. But the book itself happened more or less by accident not by design. It was the story behind it that really propelled me for years.

"The book is also a biography of Sethu Lakshmi Bayi. She was a remarkable woman who was made as queen at the age of five, started to rule in her late 20s, was pushed out of power in her late 30s, lost the kingdom completely upon Independence in her 50s, and in her 60s she left the palace and that whole world behind, and moved to Bangalore where she died as a complete nobody"

Left and below: As chief of staff to MP Shashi Tharoor, Manu Pillai was involved in work pertaining to the Parliamentary Committee for External Affairs

Left and below: As chief of staff to MP Shashi Tharoor, Manu Pillai was involved in work pertaining to the Parliamentary Committee for External AffairsI grew up in Pune. Kerala was our summer home where we went for our holidays to meet our grandparents. I graduated from Fergusson College in Economics and also obtained a Liberal Arts Diploma from Symbiosis and then went off to London. My second book especially is a tribute to the Deccan including Pune. While the first book was a tribute to my Malayali roots, ‘Rebel Sultans’ is a tribute to the place where I was nourished.

I was not much of a reader; my sister was the one who thrust a book into my hands one day and said, ok now sit down quietly and read it. Because otherwise, I was fairly restless. Somehow I got interested in that book and my interest in reading grew. Another reason why I turned to books was because we had no television to distract us. One morning, when my father caught me watching Cartoon Network at 7:30 in the morning, he simply chopped off the cable wire. That was sometime in 1997-98. After that, we were allowed to watch one BBC film a week. My parents would go to the British Council Library and bring a mini-series or film adaptations of books of legendary authors like Charles Dickens and Jane Austin. We would watch the film and then go up and read the original book. That cultivated the habit of reading. And then I picked up interest in non-fiction, which eventually led me to Sethu Lakshmi Bayi.

The advantage I had was that I was doing my masters in London when I was 20 years old. There they train you in a manner that the research methods become very clear and that corresponded with the time that I was also researching my book. So the academic guidance I got from my university for my thesis, I could apply to my own private research which I did on the side. In terms of writing it, obviously, six years meant it involved a lot. If I look at my first draft now, I would have thrown it out of the window because it was embarrassingly bad. But as time passed I realized there was no magic key where you sit up one morning, say you are gifted and become a writer instantly. That's not how it works - writing is something that comes from excessive reading; the more you read, the better you can write. It’s not merely an art; it’s also a craft. The more you read, the more you understand the craft. The art and ideas come from your head, but how you put it on paper comes from the craft. So as I advanced into my mid 20's I kept reading and reading and that kept developing my own style of writing. I did not run into writing for newspapers or magazines like a lot of my friends did. I was more or less focused on this long project. So the irony is, for example, my master’s thesis was 15,000 words, whereas for the book each chapter was about 20,000 words. In other words, each of the 13 chapters was essentially one master’s thesis! The book is voluminous – 704 pages altogether.

I often speak at various literature festivals where you end up running into the most remarkable people. Recently in Jaipur I met Indira Vishwanathan Peterson from the USA who is a scholar on the Thanjavur Marathas. Her work is fascinating. There was this Raja in Thanjavur called Serfoji in the early 19th century. We think of Indian kings as traditionalists and orthodox but this man was interested in western science and he was importing western technology. He was setting up schools, translating western textbooks into local languages. He tried to teach scientific principles to the Indian masses. He taught geography through songs and plays and so on. Then of course I have met the master of narrative history, William Dalrymple. He has written a few lines of praise on the back cover of my second book, Rebel Sultans. It’s an interesting world out there. There are a number of remarkable women writers, but I often feel that they don’t get enough attention. There are very eminent female writers - not only an Arundhati Roy who is the exception in terms of a book at that level, but very many more, regular writers as well.

"It was a matrilineal society, in which the husband didn’t matter. What matters is the woman—the family is not man, wife and children; it's woman, brother and woman’s children. So the king of Travancore does not inherit the crown from his father, he gets it because he is the son of the Maharani; his father, the Maharani’s husband is only called Consort - he is not even called a husband. He cannot sit in the presence of his wife, he cannot call his wife by name - he has to call his wife your highness"

It did, because there is a lot of reverence even now for the royal family. For example, the book discusses the status of women in great detail and when you discuss things honestly, it is bound to rustle a few feathers. But, I think even though it raised eyebrows, nobody could say anything directly. Everything I have used is archival material. I have not pulled anything out of the air; nothing is merely anecdotal, nothing is speculation - it’s all in the archives, in intelligence reports, in their diaries and in their letters. So I have got it out of their own signed documents. No one can question you when your research is solid.

Yes, that’s because it was a matrilineal society, in which the husband didn't matter. What matters is the woman, so for example, simplistically putting it—the family is not man, wife and children; it's woman, brother and woman's children. So the king of Travancore does not inherit the crown from his father, he gets it because he is the son of the Maharani; his father, the Maharani's husband is only called Consort - he is not even called a husband. He cannot sit in the presence of his wife, he cannot call his wife by name - he has to call his wife your highness. During the banquets in the palace, the Maharaja and the Maharani, that is, the brother and sister would eat four desserts, whereas the Maharani's husband would get two desserts. So in every respect, the husband's status was lower. At a more general level also this had repercussions—in the inheritance of property, in how easy divorce was to obtain, the absence of concepts like widowhood, and so on.

Very limited, in the way it is taught. But I don’t entirely blame the government either, because a government’s job is to create a history textbook. We are looking at a country that is so large, that has dozens of official languages and so many diverse cultures and religions. In a country with such diversity, so many stories, how do you encapsulate all of this in a 50-page textbook? So then they reduce it to it's bare bones, boring dates and events, simply because I suppose it is convenient to teach history that way. In the process, though, we are actually losing the richness of our own past, because it's such a layered, rich, complex and beautiful, magnificent past. It deserves far more attention.

Yes, I have realized that there is great research coming out. There is a lot of good history being done by scholars, but the problem is that it gets limited to academic circles or seminar circuits and it does not leave that scholarly realm unless you are actually genuinely interested in looking for that story. It is very difficult to find it. What you need is people to bridge rigorous academic research with an accessible narrative style, so when the narration is in an accessible, attractive way, and if the reader can melt into the story rather than read it like a dry textbook, then people do take an interest in it. My first book was written when I was 25 years old, I was an unheard-of name, I had never written before. People normally hesitate to pick up big books, so there were some people in the publishing house in Harper Collins, who wondered whether it was wise publishing this book, but the editor had faith and she insisted on it. They published and it went on to become a best seller. It’s gone through some 12-13 prints, I think, in these two and a half years. It’s won the Sahitya Akademi award; it is critically acclaimed and it convinced me that if you make the effort there is an audience; the audience will pick it up.

I made it into an attractive story. My fourth draft, which was my final draft, I wrote from the perspective of the reader. Where the reader would not get bored, she should feel that urge to turn the page, so once you get that in, you are not writing for yourself and your satisfaction, you are writing to satisfy the reader.

To know India, we must know the Deccan. We begin with the age of the Sultans of Delhi, one of whom, Alauddin by name, marched to the South at the end of the 13th century demolishing what lay accumulated from generations before. From the Alauddin Khilji era to the ascent of Shivaji, the book covers the dramatic rise and fall of the Vijayanagar Empire, the Bahmani kings and the rebel Sultans who overthrew them, Queen Chand Bibi, a valorous queen who was stabbed to death, Ibrahim II of Bijapur, Krishna Deva Raya of the Vijayanagar kingdom, among others.

He was an immensely important figure, in the sense that he came at a certain moment, he came with a new vision and started something new. Imagine, it was entirely his personal ambition that initially drove him, but what he unleashed took Maratha rule from this one small region all the way to Punjab, all the way to Bengal. Even in Tamil Nadu, there is a Maratha ruling family that was established, Shivaji’s half-brother was ruling there. So he set out and created something that really changed the history of the country itself. But there are a hundred books on Shivaji. For me the point was that I didn’t want to tackle the same subject again, because people have done that, better people have done that, older, much more experienced historians have done that. My point was, why did Shivaji emerge at that particular point, what led him in that era to the idea to do what he wanted to do? I looked at the previous four centuries and I realized that here we have a fascinating period that’s actually neglected. These pre-Shivaji Sultanates are very interesting. You think globalization is a very new phenomenon while it is not, and the Deccan Sultanates are proof of it—there were Persians, Arabs, Africans, and the Deccan was a world full of diverse cultural influences.

It was very rewarding. I met him as a 21-year-old in 2011. It was a great opportunity for me; it was the first job I ever had and he essentially gave me complete charge of his Delhi office. On hindsight I wonder why he reposed so much faith in a 21-year-old kid - I worked hard, that much I'll give myself. It was good to be on that journey, to be part of an election campaign. I was dealing with diplomats, NGO's, people on the ground with terrible tales of misery. You actually receive calls like that and we wonder how we help this person. I used to be in the office from 9 am until 10 pm, but to be frank I thoroughly enjoyed such workaholism.

I also wrote the weekly newspaper column for Mint Lounge -- I did that on the side while I was Tharoor’s chief of staff till last August. But I realized that while I could keep doing my regular columns, to write a book you need more mind-space so I decided to take a break. Instead of taking a break and just disappearing and saying I am writing a book, I thought why not do a PhD; because that way I get a degree out of it, I also get the space to do my research, and the thesis can turn out to be my next book at some point.

It's not a priority, it’s not something that gives you votes, it’s not something that the public cares very much about, so why should you bother. Part of it is also poverty. When you are a poor country, people are not so interested in culture. When you are worried about your next meal why would you be interested in preserving a monument? I don’t fully blame politicians because they are responding to the public. The future is in the role of private citizens. There is some movement in that direction; for example in Bengaluru, they are setting up the Museum of Art and Photography (MAP). The city’s great billionaires have invested money to preserve art for which they are creating the space. So I think public private partnerships are the way to go, because the private sector has money, it even has the expertise. There is one group called Ekaa Resources which does archival work and conservation and sets up museums. For example, XYZ Maharaja, who’s got this old palace that is crumbling will commission them and give them a budget saying in this budget you must set up a museum, find the staff, train the staff and get it running, and they do the whole thing. They are the ones who are also involved in the Indira Gandhi exhibition, the centenary exhibition that is travelling around the country. So there are private players who are interested; it’s a question of where the money will come from, and the money has to come from the private sector. For example if you are living in Pune, pool together your resources, adopt one or two monuments and make it a world class attraction. It will be a contribution for now as well as for future generations.

I have started writing, but won’t talk about till it’s done, I am a little superstitious. I feel you shouldn’t count your chickens before hand. The good thing is—and this is in continuation of my earlier point on private investment in the sphere of heritage—I have the backing of the Sandeep and Gitanjali Maini Foundation in Bengaluru, and this allows me to really focus on my work and invest in my research, at a much better scale than I was able to do earlier.

People keep saying, youngest historian, and all of that, but you know these titles don’t really matter. There are other young historians also coming up, in different fields. There is Vikram Sampath who did this fabulous biography of vocalist Gauhar Jaan who is actually a striking figure - she was one of the earliest people who sang for the gramophone.

Seventy years of independence is not a long time if you look at the large scheme of things, so we are still a country that is figuring out who we are, what our principles and values are. The two main political parties can’t agree on the core values of this country, which means that that’s very much up for debate even today. People have not figured out who we are as Indians, that is still something we are negotiating. So the emphasis is often on modern history, the nationalist struggle, Indira Gandhi - there is a profound interest among let’s say the intellectual classes also in this here-and-now history, whereas what I am interested is in something earlier. Because I am more interested in reminding people... for example when there is Hindu-Muslim polarization, a character like this Ibrahim Adil Shah who brought together the best of both is someone who reminds us that we don’t always have to go to the worst, we can also emulate the best that existed. I am not saying that there weren’t cruel rulers in the past, I am not saying there was no violence in the past, but I am saying just as there was that, there were also people who were trying to do the opposite, so why are we emphasizing on the negative when we can learn from the positives?

"Seventy years of independence is not a long time, if you look at the large scheme of things, so we are still a country that is figuring out who we are, what our principles and values are. The two main political parties can’t agree on the core values of this country, which means that, that’s very much up for debate even today. People have not figured out who we are as Indians -- that is still something we are negotiating"

In fact, the irony is that some of our best records are sitting in their archives, because here they are rotting away, but they preserve their copies. The archive itself is a spectacular sort of space because you can’t enter with your bag; you have to enter only with a clear plastic bag, you cannot take a pen inside because a pen can damage things; you can take a pencil, as they can at least erase it. When you leave, they check this plastic bag, but if you have a laptop, you need to open the laptop and show that you are not stealing anything. All the documents are kept in temperature-controlled rooms and they come to you in these leather folders and if they are very delicate they come to you in microfilm, obviously. So you don’t actually touch the original and the way it’s preserved the way it's brought to you, the systematic way in which it is run is so impressive. And I have seen archives here where you give an order and four hours later they come to you saying 'Haan catalogue mein to hain magar it's missing'. I am like, 'achha —but how can it be missing, who is responsible? But there’s no accountability. The government is trying to make it more streamlined through digitization, so these are welcome changes for a country with so much history.

Yes, it gives me a good working environment; it gives me access to the best books. The British Library where I normally sit every day is called a legal deposit library; which means, by law, one copy of any book published in the UK has to go there - which means that for the past God knows how many hundreds of years, anything published in the UK is available there. I have found obscure books by Indian authors who you wouldn’t come across in an Indian book store. Books that have gone out of print in the 50's and 60’s are available here. Besides, of course, the unbelievable collection of records and documents including Sanskrit manuscripts. When I was doing my research on Kerala’s history, one of the earliest enclaves the British had was a place called Anjengo which was granted by the Queen of Travancore to the British. The original Malayalam record from 1694-95 has gone missing in India, but the English side of that record is still available in London.

I normally sit down there at around 10 am until 7.45 p m, as the library shuts down at 8 pm. I am not an introvert, so sometimes it’s very frustrating because there are days when I have not uttered a word to anybody, because you are sitting with your books in a library and you can’t talk. Sometimes I run into colleagues and friends but everyone is in their own PhD mood. Socializing often happens only on the weekends, not on weekdays.

Yes, it’s a public library. As I said, they value research, so technically any member of the public, so long as they say what they are interested in, are immediately given a pass. So it’s quite magnificent.

Work hard, don’t complain too much, because even to have the freedom to complain is a luxury in this country. There are people who deal with such unbelievable depths of misery that this attitude of complaining is not a very wise one. I have learnt to look at the bigger picture. Which means that here and now even if I don’t like something, in the bigger picture, it may pan out better, so I don’t immediately get outraged or go ballistic about it. I have realized there is something called the long perspective, and focusing on the long term and just thinking with common sense normally guides me into the right place. I normally think out and plan out my goals for each year.

By Vinita Deshmukh