An Express Investigation - Part IV: As engineering seats go unfilled across the country, as Brand BE/BTech steadily loses its lure, what explains Karnataka’s relative success?

The SJC Institute of Technology in Chikkaballapur, Karnataka, is run by the Sri Adichunchanagiri Mahasamsthana Mutt

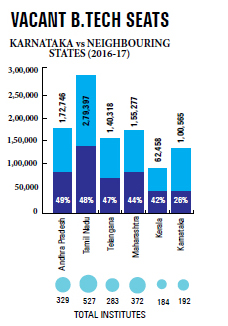

The SJC Institute of Technology in Chikkaballapur, Karnataka, is run by the Sri Adichunchanagiri Mahasamsthana MuttKarnataka, with the sixth largest number of undergraduate engineering seats (1,00,565) in the country, is the state with the least vacancies among the top 10 states that together account for 80 per cent of the total seats. Of the 153 engineering colleges being monitored by the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) for poor admissions, only three are in Karnataka.

As engineering seats go unfilled across the country, as desperate colleges lower the bar to get students, as the poor quality of graduates and their lack of employability threaten to undermine India’s demographic dividend, as Brand BE/BTech steadily loses its lure, what explains Karnataka’s relative success?

A set of factors that could hold pointers to the way ahead, say experts.

The engineering boom first arrived in Karnataka. In fact, the first private engineering colleges in the country— BMS College of Engineering in Bengaluru and National Institute of Engineering in Mysore—were set up here in 1946. Much before the IT industry came up in 1991, Karnataka had an ecosystem of engineering excellence. The state had institutions such as the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL). Currently, Bengaluru is the fourth largest technology cluster in the world after Silicon Valley, Boston and London. It also has the largest number of R&D centres in the country. In short, a ready market for those who graduated from its engineering colleges.

“Let’s not forget that BTech is a professional degree. You pursue it with the intention of getting a job. Let’s say, you graduate from some ordinary college in Lucknow, is there a job on offer? The answer is no. The problem of vacant seats arises because colleges have come up in areas with absolutely no industry to absorb engineers,” says Sanjay Dhande, former director of IIT Kanpur.

Former Infosys director T. V. Mohandas Pai, who is currently Chairman of Manipal Global Education, agrees, saying Karnataka did well to ensure that its colleges were “clustered near urban centres”. “You need to start colleges in urban areas to get good faculty. Why would a teacher want to move his family to a remote area where there aren’t any facilities and good schools?,” he says.

According to state government data, almost 100 of the state’s 192 engineering colleges are either in or around Bengaluru.

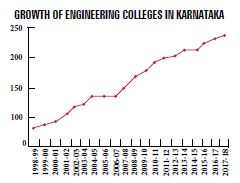

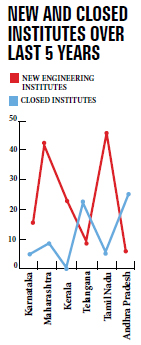

Despite the early start and though Karnataka continues to retain its position as a premier software export hub, the expansion in the number of engineering institutes in the state hasn’t been as unbridled as in the rest of the country, according to experts and stakeholders interviewed by The Indian Express.

“There has been a fairly controlled enhancement of intake (in Karnataka) because the market here responds very ably. The number of institutes is not as big as in Andhra, Tamil Nadu or even UP,” says R Natarajan, who headed AICTE from 1995 to 2001 and who now lives in Bengaluru.

According to AICTE data, the state had 192 institutes in 2016 as opposed to 527 in Tamil Nadu, 372 in Maharashtra, 329 in Andhra Pradesh, 283 in Telangana and 296 in Uttar Pradesh. Even Kerala, a state one-fifth the size of Karnataka, had 164 colleges, with 42% of its BE/BTech seats vacant in 2016-17.

Old-timers, however, say the expansion wasn’t always this “controlled”.

K. Balaveera Reddy, former vice-chancellor of Visvesvaraya Technology University (VTU), Belgaum, who now lives in Bengaluru, says several new engineering colleges came up in the 1970s and early 1980s. During this time, it attracted students from all over the country, including bordering states such as Andhra Pradesh.

“I remember, even till the late 90s, there used to be special trains from cities such as Delhi and Kolkata to Bangalore to accommodate students travelling to appear for the CET (Common Entrance Test),” says Reddy.

Although this rapid expansion is fairly well-known, not many are aware of a short period of consolidation, says D. K. Subramanian, a retired professor of Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bengaluru and the country’s first PhD in Computer Science. He feels Karnataka is better off now because of an “informal moratorium” imposed by the state government in the early 1990s.

“You won’t find anything about this on the internet because (the moratorium) wasn’t a proper policy decision, but during that period, the government did not allow any new engineering colleges to come up. That, in my opinion, went a long way in arresting the unsustainable growth in Karnataka,” he says.

According to data accessed by The Indian Express, only one new engineering college was approved in the state in the six years between 1989-90 and 1994-95. Between 2000 and 2017, there have been only six years when the number of new colleges touched double digits.

If fewer engineering colleges were the only solution to the vacancy crisis, then why did Madhya Pradesh, with roughly the same BTech intake as Karnataka, have almost 60 per cent of its seats vacant last year?

But if fewer engineering colleges were the only solution to the vacancy crisis, then why did Madhya Pradesh, with roughly the same BTech intake as Karnataka, have almost 60 per cent of its seats vacant last year?

The answer, say experts, lies in better quality of education and employment opportunities. And that’s where Karnataka has an edge, they say.

Drawing from his experience as a member of AICTE’s inspection team for about 10 years, Subramanian says, “I noticed a remarkable difference in faculty (between those in Karnataka colleges and elsewhere). Because the state had a head start in engineering education, it meant they had a much larger pool of qualified faculty to choose from. Quality of education, as a result, has always been better in the state. In fact, when other states went through their respective boom periods, Karnataka even provided them faculty.” He is currently on the research advisory board of Tata Consultancy Services.

The state’s success story has a curious religious angle —the involvement in education of mutts or monasteries that are usually caste-based and wield immense political and social clout. Almost all of the state’s mutts have set up educational institutions as part of their ‘social service’, many of them engineering colleges.

According to Vaman B. Guddu, Special Officer (Academic) at VTU, the university in Belgaum that affiliates all engineering colleges in the state, at least 15 engineering colleges in Karnataka are run by mutts.

Experts say this association has helped put the brakes on the unbridled expansion of engineering education since, unlike in other states, the increase was based on “real and not speculative demand”.

“If you look at the history of education in our state, mutts have played a role and this is unique to Karnataka. A religious organisation usually doesn’t treat education as a business. It sees it as a social obligation,” says Karisiddappa, the incumbent vice-chancellor of VTU, the affiliating university for all engineering colleges in the state.

The SJC Institute of Technology in Chikkaballapur district of Karnataka is one such college. It’s run by the Sri Adichunchanagiri Mahasamsthana Mutt, which is revered by the agrarian Vokkaliga community in the state. Last year, only four per cent of its seats were vacant.

According to college principal K.M. Ravikumar, a mutt’s decision to start an institution is driven by demand as well as viability. “Mutts (before establishing any educational institution) conduct surveys. They ensure that there is a need (for a new institution) before starting one and that the mutt should not suffer financially.

In other states, competition comes before viability,” he explains.

“Before SJC was set up, the local population of Chikkaballapur had to travel 50 km to Bengaluru to study engineering. So there was a demand for an engineering institute here and SJC was established after the followers in Chikkaballapur approached our mutt. One per cent of the funds were donated by the local population and the remaining was invested by the mutt,” he adds.

Karnataka may be better off compared to most states, but it still has a problem. The proportion of unfilled seats has been gradually increasing for the last five years—from 22 per cent in 2012-13 to 26 per cent last year.

According to H. U. Talawar, director of technical education in Karnataka, the state has started work on a perspective plan to ascertain the demand for engineers in future and approve new institutions accordingly.

“We need to have a perspective plan. We try to assess the need for doctors and IAS officers, so why can’t we make a similar assessment for engineers? Accordingly, we can streamline our education system,” says Karisiddappa.

(This article was originally published in The Indian Express)

(http://indianexpress.com/article/education/ devalued-degree-least-empty-seats-in-karnatakahas- lessons-for-other-campuses-4981588/)

by Dr (Col.) A. Balasubramanian