An Express Investigation - Part III: The middlemen are part of an ecosystem created by an uneven growth in engineering colleges over the last decade

The lone first-year IT student at Marathwada

Institute of Technology, Bulandshahr

The lone first-year IT student at Marathwada

Institute of Technology, BulandshahrWhen no one comes knocking on your door, you send a “middleman” to lure them in—that, in short, is the unstated admissions policy of many engineering colleges staring at seat after empty seat.

Ask Jainendr Yadav, 39, and he is not at all on the defensive. “They don’t mess with us,” he says with a smile that rarely leaves his face. “We are a parallel government of sorts.” His confidence isn’t misplaced. At a time when engineering colleges in Uttar Pradesh (UP) show a 65 per cent vacancy, at least 14 points above the national average, Yadav and many like him control access to the colleges’ lifeline—students.

Every year, from February to August, Yadav, a “consultant” on paper, taps his network of sub-agents who send out bulk SMSes and work telephone lines to lure engineering aspirants. He places them in colleges in UP in exchange for a commission from the institute. Given their desperation, colleges pay up to Rs.60,000 for every he helps enroll. With 10 years of experience, Yadav claims to cater to roughly 100 educational institutes in UP. Last year, he says, he “placed” over 50 students into B Tech programmes.

Yadav and middlemen like him are part of an ecosystem created by an uneven growth in engineering colleges over the last decade, a phenomenon that has resulted in seats going vacant and the degree getting steadily devalued. Of the 15.5 lakh undergraduate seats in 3,291 engineering colleges in India, over half—51 per cent—were vacant in 2016-17, according to data from the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), the apex body for technical education in the country.

Uttar Pradesh is second on the list of vacant seats after Haryana, where 74 per cent of the seats went unfilled last year.

UP has 1.42 lakh B E/B Tech seats, the fourth largest in the country after Maharashtra, which has 1.55 lakh seats. According to rules laid down by the Dr APJ Abdul Kalam Technical University (AKTU) in Lucknow, the affiliating university for all private engineering colleges in the state, every institute has to fill 85 per cent of its intake through the Uttar Pradesh State Entrance Examination and AKTU counselling and the remaining 15 per cent through management quota.

If the 85 per cent seats are not filled through counselling, colleges are permitted to admit students directly, through the management quota.

In 2015, only 15,608 students were admitted across all engineering colleges in UP via counselling. Last year, this number stood at 13,730. That’s barely 10 per cent of the intake. However, even after direct admissions, 65 per cent of the total 1.42 lakh B E/B Tech seats were left unoccupied last year.

This is where the likes of Yadav come in. “A small-time agent today can easily earn Rs.10 lakh a year working from home,” says Yadav, who wound up his office in Delhi a few years ago and now operates from a rented house in Greater Noida.

Jainendr Yadav, a ‘consultant’, claims to have got 50 students

into engineering colleges in UP last year

Jainendr Yadav, a ‘consultant’, claims to have got 50 students

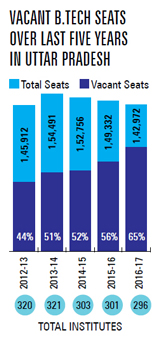

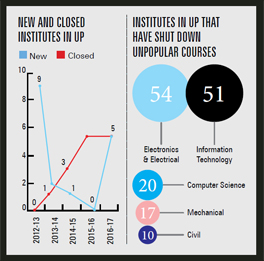

into engineering colleges in UP last yearIn 2000, UP changed rules to permit private players to set up engineering colleges. The result was a sudden spike in colleges and seats across the state. In 2002-03, there were 22,491 undergraduate engineering seats across 83 colleges. In the 15 years since then, that has gone up to 1.42 lakh seats (a 535 per cent increase) and 296 colleges (a 296 per cent growth).

This sharp growth curve began petering out in the late 2000s. The downward slide began in 2012-13 and the graph has continued to drop ever since—44 per cent engineering seats went vacant that year; in 2016-17, it stood at 65 per cent.

Last year, over half—or 58 per cent—of the engineering colleges in the state had at least 70 per cent of their seats vacant. At least 11 of these colleges now run the risk of being forced to shut by AICTE since they haven’t been able to fill more than 30 per cent seats over the last five years. That is the sixth highest number of colleges under the regulator’s radar after Maharashtra (26), Andhra Pradesh (19), Haryana (17), Orissa (17) and Telangana (16).

Given this, the presence of middlemen points to a worrying lowering of standards, say experts.

“The phenomenon of middlemen is completely avoidable. Their existence reflects that there are gains to be made and shared. After all, these intermediaries have to be paid by those providing education. A situation where you have middlemen sourcing students is not a happy one at all, especially if you are trying to improve the quality of education.”

Yadav, the agent, admits as much. “Meritorious students will never take admission through us. It’s the weaker ones who approach us. Since colleges are desperate, they even take in students who have barely any understanding of mathematics. I’m not sure if these students learn anything at all,” he says.

Chandan Kumar, managing director of SPOC India Global Services, a six-year-old consultancy firm in Noida, says that institutes willingly dilute admission criteria, with most of them waiving the requirement that the student should have at least appeared for the state entrance test.

Kumar’s firm has tie-ups with close to 70 institutes, of which almost 50 run B E/B Tech programmes. He says that often, the student’s aptitude has little to do with her chances of getting into an engineering college. Anybody with 45 per cent marks—the minimum eligibility norm prescribed by AICTE for admission to an undergraduate engineering course—and who is ready to pay an agent can be assured of a seat.

The informal and unregulated nature of the sector makes it difficult to map the growth of middlemen. The Indian Express spoke to three agents on record, all of whom spoke about how colleges in the state were desperate for students and therefore increasingly dependent on middlemen for survival.

Meena Saxena, 44, says she handled the ‘admissions cell’ of several technical institutes in UP, including GL Bajaj Institute of Technology Management and Accurate Institute of Technology and Management, for 18 years before starting her own “consultancy practice” in Noida two years ago. “A decade ago, when admissions were good, consultants would request institutes to admit students for a hefty donation. Now colleges beg the agent to bring in students,” says Saxena, who claims to have about 50 clients, including engineering and management institutes in UP.

The biggest indicator of their growing clout is the fee middlemen command. “In 2010, I remember, the commission for placing one student was Rs.5,000. Today it’s at least Rs.60,000,” says Yadav, adding that in their books, colleges usually show the payment made to agents under the head “branding”.

Before the vacancy crisis came up, an agent’s commission used to be a “cut” from the capitation fee (donation) paid by the parents. With supply (read seats) outstripping demand, colleges are no longer in a position to demand capitation fee. So, colleges now offer agents a cut from a student’s first-year tuition fee—ranging from Rs.25,000 to Rs.60,000.

A sign of their growing dependence on “consultants” is the manner in which colleges are seeking longer and even permanent associations with the middlemen. “For the last two years, they have also started offering us a share in the institute’s annual revenue. Many have even outsourced their ‘admissions cell’ operations to consultants,” says Kumar of consultancy firm SPOC India.

The industry of middlemen in UP, which operates mainly out of Noida, runs on word-of-mouth references. But that happens only once an agent has established herself in the sector. To make a mark, you first need to build a good database of students, says Saxena. For instance, she has an informal arrangement with a few schools where she helps with “career-counselling” and conducts aptitude tests for students. The school administration, in turn, provides her with contact details of all of its Class 12 pupils and she reaches out to them as soon as the Board exams are over.

Himanshu Raghav, 17, and his twin, Harshit, at Marathwada Institute of Technology in Bulandshahr, UP. They were the only ones admitted to the first-year batch of IT and Electronics Engineering, respectively

Himanshu Raghav, 17, and his twin, Harshit, at Marathwada Institute of Technology in Bulandshahr, UP. They were the only ones admitted to the first-year batch of IT and Electronics Engineering, respectivelyBut with interest in engineering flagging, agents have realised that it’s not enough to tap the local student population. So they have begun fanning out to different parts of the country in search of aspirants, with Bihar now their perfect hunting ground.

“If it weren’t for students from Bihar, half of us and the institutes would have gone bust by now. Seventy per cent of our business comes from there,” says Yadav, who visits Bihar at least twice a month to “build contacts”.

Why Bihar? Agents say that with few educational opportunities in the state, students there are happy to take up seats elsewhere in the country. The engineering wave that swept the country seems to have skipped Bihar. Until last year, the state only had 31 AICTE-approved engineering colleges (10,130 seats) while Haryana had 144, Punjab 103, West Bengal 91, Odisha 96 and UP 296.

The Vishveshwarya Institute of Engineering and Technology (VIET) in Ghaziabad, set up in 2000, took in 20 students from Bihar last year and another 20 this year through a consultant, says institute head, Vinod Choudhury. The college is among 11 institutes in UP on AICTE’s radar for low admissions. Last year, as per AICTE records, over 80 per cent of its 480 B Tech seats were vacant. Two years ago, there were two engineering colleges running from the same campus— VIET and Vishveswarya Institute of Technology (VIT). The latter was started in 2008-09, with a sanctioned strength of 240 seats, to meet what they thought would be a rising demand for seats, but was closed five years later following poor admission numbers. Now the building is a branch of Delhi Public School.

When no one comes knocking on your door, you send a “middleman” to lure them in—that, in short, is the unstated admissions policy of many engineering colleges staring at seat after empty seat

There are some colleges that are still holding out despite the embarrassing admission numbers. Marathwada Institute of Technology (MIT) in Bulandshahr has decided to not approach middlemen, instead marketing its programmes more aggressively. This year, only 16 students have been admitted against an intake of 330 B E/B Tech seats.

When they joined the college this year, Himanshu Raghav, 17, and his twin, Harshit Raghav, discovered that they were the only ones admitted to the first-year batch of IT and Electronics Engineering, respectively. “I figured out I was the only one after the roll call on the first day,” says Himanshu. He is the only student who secured a seat at MIT through AKTU counselling this year.

At the moment, the brothers say, they are not sure things will work out. “But I don’t mind being the only student in my batch. Our father is happy because he thinks we will get special attention from the teachers,” says Harshit. MIT has a sanctioned strength of 30 seats for IT engineering and 60 for electronics. This is the first time the college has had a single-student batch in both branches. “It’s an unusual situation. Classes will happen even if it means assigning one teacher to one student,” says MIT director Atul Choudhury.

The college is on AICTE’s radar for poor admissions over the last five years. Last year, according to AICTE data, 89 per cent of its 330 first-year seats were vacant. The institute, in a bid to tide over this crisis, has started offering skilling courses from this year under the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana and has already admitted 250 students.

The UP government is planning to draft a perspective plan to address the crisis of vacant seats. On November 8, it wrote to all technical institutions seeking their feedback on seven proposed action points, including a moratorium on new approvals.

But heads of AICTE-approved colleges say a part of the problem lies elsewhere—the “unchecked” expansion of engineering seats by private and deemed universities, which are not regulated by AICTE. These ‘universities’ are established under the Uttar Pradesh State Universities Act, 1973, and come within the purview of University Grants Commission (UGC), not AICTE.

UP has witnessed a steady rise in the number of private universities that offer engineering programmes. The state has 29 of these ‘universities’, the third largest after Rajasthan (46) and Gujarat (31).

College heads say that once a private university gets permission to start an engineering programme, they have a free hand in changing the fee structure and starting new course. But an AICTE-approved institution, on the other hand, needs to seek permission before attempting any of the above. “AICTE allows an intake of 60 students in an institution after several inspections. But a private university can admit hundreds of students without seeking any approval,” says Choudhury, head of VIET institute in Ghaziabad. “At this rate, one day, everyone in UP will be an engineer.” An unskilled, unemployed one at that.

(This article was originally published in The Indian Express) (Link: http://indianexpress.com/article/education/devalued-degree-to-fillempty- seats-colleges-lower-bar-hire-agents-to-cast-their-net-4980288/)

Dr (Col.) A. Balasubramanian