An Express Investigation - Part II: As many as 18 engineering institutes have closed down in Haryana since 2012, the third largest number after Andhra Pradesh (23 colleges wound up) and Telangana (21)

While Rayat Bahra IITM college (right) in Sonepat

shut down earlier this year, next door, the Tek Chand Mann College is now Modern Convent School

While Rayat Bahra IITM college (right) in Sonepat

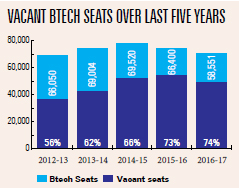

shut down earlier this year, next door, the Tek Chand Mann College is now Modern Convent SchoolTo listen to the death knell of an undergraduate engineering degree, come to the graveyard—Haryana which, at 74%, tops the vacant seat list in the country and its Sonepat district, home to the state’s private education hub. Launched in 2006 by then Haryana Governor Jagannath Pahadia, Shri Balwant Singh Institute of Technology (SBIT), spread over 10 acres, is a textbook example of what has gone wrong.

Last August, when its second-year students returned from their vacation, they found that most of their teachers had left. “For almost two weeks, there was no one to take classes for four of our papers,” says a Computer Science student who did not wish to be identified. “The college then replaced our teachers with B.Tech graduates, some of them fresh out of college.”

As for first-years, a school teacher was brought in to teach thermodynamics— from the school across the road run by the same group.

Clearly, these violated norms mandated by the All India Council of Technical Education, the apex body of engineering colleges in the country, according to which teachers at the entry level (assistant professor) should have had a postgraduate (M.E/Tech) degree.

But AICTE norms have long gone out of the window at colleges like SBIT—a testament itself to the laxity in regulation and the close-your-eyesee- no-evil approach to colleges (see box).

No wonder, 97% of its first-year seats are unfilled this academic session— 17 students against an intake of 540 B.E/B.Tech seats. Almost one half of the campus remains inaccessible to students. “The institute runs up a power bill of almost Rs.2 lakh a month. We couldn’t afford to keep all classrooms functional,” says an administrative officer at SBIT.

Of the first-year batch of 17, 13 are in Computer Science, four in Mechanical Engineering — not one has opted for Electrical, Electronics and Information Technology this year.

The Indian Express could not reach college chairman Sushil Yadav or institute director V. K. Panchal. Both were not available when The Indian Express visited the campus and did not answer calls and SMSes left on their mobile phones.

The story of SBIT is illustrative. As many as 18 engineering institutes have closed down in Haryana since 2012, the third largest number after Andhra Pradesh (23 colleges wound up) and Telangana (21). AICTE records investigated by The Indian Express show 17 institutes in the state are currently on the regulator’s radar for low admissions and run the risk of forced closure next year.

This, again, is the third largest number after Maharashtra (26) and Andhra Pradesh (19) though Haryana has, at 58,551, half the number of B.Tech seats as Maharashtra.

Haryana’s Sonepat district, home to 17 engineering colleges as of 2016- 17, the highest in the state, is now pockmarked with failed institutions. According to AICTE data, three colleges have closed down in this district in the last five years but the situation on the ground is worse – a visit revealed at least five had shut shop indicating that there were colleges winding up without informing AICTE.

Things weren’t always this bad. Haryana was late to join the engineering bandwagon that the country rode in the mid-1990s—fuelled by the IT boom of that period—but when it did, like elsewhere, colleges mushroomed across the state helped by the ease with which the AICTE granted approvals. In fact, 74 per cent of the total engineering institutions in the state i.e. 106 out of 144 that offer undergraduate courses were set up only in the last decade.

“Many of these colleges came up in Sonepat. Its proximity to Delhi meant better job opportunities for the graduates,” says Bachan Singh, deputy director and registrar at Bharat Institute of Technology (BIT), which was established in 2008. Last year, 89 per cent of the college’s 420 B.Tech seats were empty and the institute is surviving on revenue generated from the pharmacy college next door run by its parent group, Bharat Group of Institutions.

Until 2009, the nearby Bhagwan Parsuram College of Engineering, whose last batch graduated in 2016 and which has had no fresh admissions since 2013, had nine buses to ferry students from Delhi and all over Haryana to the institute. The college is now largely under lock and key with part of it leased out to a wrestling academy.

S. K. Bhardwaj, 62, the college principal who now lives in Gurgaon, says, “In 2009, we had almost 1,400 B.Tech students across all four batches. In fact, we increased our seat intake the same year and even started building a new academic block in 2010 for new classrooms to keep pace with the burgeoning demand.”

Experts point out that this ‘indiscriminate expansion’ in Haryana also coincided with a period when AICTE was accused of rampant corruption.

According to AICTE data, 2008- 09 witnessed an increase of almost 30 per cent in engineering intake over the previous year—the highest in a single year since 2001—with over 700 new engineering institutes being approved, 41 of these in Haryana.

That year, the CBI caught then AICTE member-secretary K. Narayan Rao accepting a bribe from the owner of an engineering college in Andhra Pradesh. The incident eventually led to the suspension of then AICTE chairman R. A. Yadav.

With the global economic crisis of 2008 slowing down growth in US and Europe, the main markets for IT companies, the job market shrunk. Like elsewhere, Haryana was hit hard.

College principals say the first slump in fresh admissions was witnessed in 2011, when big companies stayed away from campus interviews. Last year, less than half of the 180 final-year students at BIT were placed through campus recruitment. Bachan Singh admits that only 25 to 30 per cent of the graduates usually find jobs now, a big shift from the 60 to 65 per cent placement rates about six years ago.

The combination of poor student intake and poor placements have trapped institutes in a “vicious cycle”, says Vinod Dhar, who was in charge of the placement cell at SBIT for almost six years until he quit four months ago. “When companies visit a college campus for recruitment, they expect a pool of at least 150 to 200 students to choose from. Why would a company want to come to your campus when your batch of graduates is as small as 30 to 40? This is a big reason why colleges haven’t been able to attract companies now. This is also the reason why more and more institutes in Haryana are holding their placement drives together so that companies have a larger pool to choose from.”

EXPERTS SAY that at the heart of the rampant mushrooming of engineering colleges lies AICTE's weak monitoring mechanism.

AlCTE OFFICIALS who spoke to The Indian Express said the Council, in most cases, did not revisit engineering colleges for years after giving its approval. In fact, an inspection team of AICTE would only visit institutes to probe the veracity of a complaint or when the institute sought permission to increase student intake. That too did not happen too often in the past, said AlCTE chairman Anil Sahasrabudhe.

WHEN ASKED when was the last time AICTE inspection team visited the campus, BlT deputy registrar Bachan Singh said he didn't remember.

SAHASRABUDHE, HOWEVER, said things were changing. Last year, AlCTE decided to revisit technical institutions before the first batch graduated and also conduct surprise inspections at 5% of the institutes every year. "We realised that the current system based on selfdisclosure was not working," he said.

The year 2011, says Bachan Singh of BIT, was the inflection point. “We had good companies visiting our college till 2010. Maybe it’s a problem of oversupply (of students) or a slump in the economy but now only BPOs participate. These jobs pay little. Moreover, why would an engineer want to work at a call centre,” Singh says.

Industry leaders, college principals and academics The Indian Express spoke to agree on reasons—poor quality of both students and faculty exacerbated by lower eligibility norms and an outdated syllabus.

Mohandas Pai, former Infosys board member and chairman of Manipal Global Education, says he has a theory for why IT companies, which are among the largest recruiters of engineers in the country, may have deserted colleges in Haryana.

“Colleges in North India have a problem. People here are not taught to speak in English. This (IT) is a global industry. If your communication skills are not strong, then the (job) opportunities will be less. So if you ask me, Haryana having a large number of vacant seats is not a surprise,” he says.

Unlike states such as Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh, Haryana has no common entrance test for admissions to undergraduate engineering colleges. It does, however, conduct online counselling based on the JEE (Main) merit list. If institutes fail to fill their seats through online counselling, they are free to admit students directly and it’s this route that most colleges in Haryana take.

The minimum requirement for students to secure a B.Tech seat is an aggregate score of 45 per cent in Physics, Chemistry and Mathematics. The eligibility criterion, laid down by AICTE, was 50% until 2011.

“AICTE may have lowered the bar from 50 per cent to 45 under pressure from institutes suffering from low admissions. There’s only so much a teacher can do to make such students (with bare minimum pass marks) excellent engineers. This eventually affects job placements. So institutes are trapped in a vicious cycle,” says Dhar, the former placement officer at SBIT.

With poor admissions reducing revenues to a trickle, a few years ago, institutes started cutting corners. Faculty was the first casualty with unpaid salaries and work pressure taking a toll on those who stayed back.

“Private colleges depend on student fee to sustain themselves. Fewer students meant fall in revenue and this affected us (teachers) directly. I did not get an increment for almost seven years and to make matters worse, our salaries never came on time. A delay of two to three months was considered normal,” says a teacher at SBIT who did not wish to be identified as he was still waiting for the college to clear his dues.

Teachers say that it’s unfair to blame them for the poor quality of graduates. “Once faculty started quitting, many of those who stayed back had to teach as many as five papers. Our output will obviously get affected under such a work burden. You cannot expect a teacher of computer science to teach a paper on e-commerce,” says a former teacher of the college who too did not want to be identified.

With the global economic crisis of 2008 slowing down growth in US and Europe, the main markets for IT companies, the job market shrunk. Like elsewhere, Haryana was hit hard growth in US and Europe

The computer lab at Bhagwan Parshuram College in Sonepat lies locked up

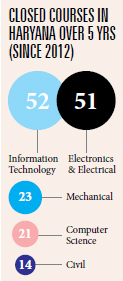

The computer lab at Bhagwan Parshuram College in Sonepat lies locked upColleges also began downsizing, surrendering seats in courses with few takers. According to AICTE data for the last five years, 52 institutes in Haryana wound up their Information Technology programme, 51 their Electrical and Electronics engineering branch and 23 of Mechanical Engineering. BIT, for instance, surrendered all its IT seats to AICTE three years ago.

But the crisis staring engineering has translated into a boom of sorts for another sector—school education.

Of the five closed institutes that The Indian Express visited in Sonepat, three—Rukmini Devi College of Engineering and Allied Sciences, Tek Chand Mann College of Engineering and Sonipat Institute of Engineering and Mangement—have been converted into schools.

Tek Chand Mann College of Engineering started in 2008 but wound up seven years later, in 2015, after filling less than 30 per cent of the seats in 2013 and 2014. Its 11-acre campus is now called the Modern Convent School, with 500 students up to Class 8.

Some others, meanwhile, have doggedly hung on. Bhagwan Parsuram College, the college a part of which is now an akhada, has been renewing its AICTE approval every year in the hope that the interest in engineering education will revive and its fortunes see a reversal.

“Even this year, we paid Rs.3 lakh (to renew AICTE approval) though we didn’t admit any students. This is just is a phase and we are confident the students will come back,” says Bhardwaj.

AICTE’s warning to institutes with 30 per cent or more seats vacant to shape up or ship out hasn’t found too many takers. “If you go to them (AICTE) today with a proposal they will allow you to set up an institute. They didn’t look at viability (when we were opening our institute), then why look at it now? If they shut us down, who will repay us for the investment we have made? Why don’t they take over these colleges, instead of shutting them down? Only then will they know how difficult it is to run one,” says the administrative official at SBIT.

(This article was originally published in The Indian Express) (Link: http://indianexpress.com/article/education/devalued-degree- 7-of-10-seats-empty-in-engineering-graveyard-few-lessons-come-tolife- 4978717/)

Dr (Col.) A. Balasubramanian