The fourth-year Electronics batch at MIT Bulandshahr, UP, has 12 students against a sanctioned strength of 60

The fourth-year Electronics batch at MIT Bulandshahr, UP, has 12 students against a sanctioned strength of 60The arena at the Yogeshwar Dutt Wrestling Academy in Bali, a village near Sonepat, Haryana, comes alive with shouts of “laga, daav laga” each time someone executes a manoeuvre. Here, every afternoon, some 50 trainees in red or blue singlets slam into each other on blue mats, under the supervision of the London Olympics bronze medallist. Until early 2016, the sights and sounds of this space were a little different— this was part of the workshop for mechanical engineering students of the Bhagwan Parshuram College of Engineering.

“We had 60 students of mechanical engineering in the last batch (of 115) that graduated in 2016. Where you now see blue wrestling mats were several lathe machines,” says S. K. Bhardwaj, 62, principal of the college whose management offered a part of the 27-acre campus to Dutt on a five-year lease.

The decision was inevitable. With not a single new admission to any of the five departments of engineering —computer science, civil, mechanical, electrical and electronics—in the last four years, this, as Bhardwaj explains, was the only way to ensure that the institute was not laid to waste.

The teachers were all laid off in 2015 and Bhardwaj has since moved in with his children in Gurgaon.

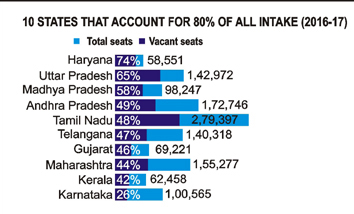

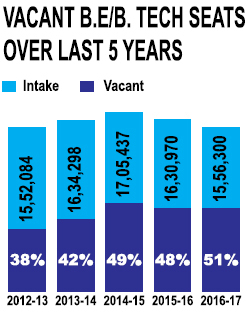

Of the 15.5 lakh BE/B Tech seats in 3,291 engineering colleges across the country, over half—51%—were vacant in 2016-17, according to data obtained by The Indian Express from the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), the apex body for technical education in the country.

The akhada and the vacant benches at Bhagwan Parshuram College tell the story of this crisis staring engineering, which makes up over 70% of the county’s technical education. Management (MBA), pharmacy, computer applications (MCA), architecture, town planning, hotel management and ‘applied arts and crafts’ form the rest.

Last year, roughly 8 lakh BE/B Tech students graduated, but only about 40% got jobs through campus placement. According to AICTE data, campus placements has been under 50% for the last five years.

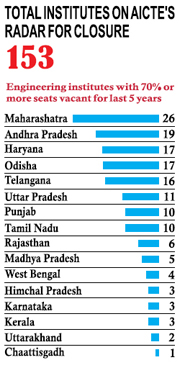

This mismatch that underlines the reality of unfilled seats has got AICTE to consider asking technical education institutes which have had 70% or more vacant seats for the last five years to wind up and leave.

Those on their last legs are now taking desperate measures—from offering fee concessions to diluting admission criteria; from paying middlemen to bring in students to hiring underqualified faculty; and, as the Bhagwan Parashuram college in Sonepat has done, letting out part of the campus or even converting the colleges into schools.

Several factors, say experts, but most of them point to what they call the engineering boom that started in 1995 and peaked in the 2000s, fuelled by the IT phenomemon and the Y2K bug. Speaking to The Indian Express, AICTE chairman Anil Sahasrabudhe says, “A large number of people were required for coding then. Your engineering branch did not matter. There was always a job for an engineer in an IT company.” He says that the Union government at that time “may have also been liberal” in approving new colleges as it was focused on enhancing the Gross Enrollment Ratio in higher education.

As a result, several private institutes came up to feed the industry’s appetite for engineers. “When there was a demand for engineers, the private sector stepped in. A large number of government colleges did not immediately get into modern branches of engineering such as IT and computer science. Our entire IT industry would have collapsed had it not been for these private institutes,” says retired IISc professor D. K. Subramaniam, who is on TCS’s Research Advisory Board.

“I remember how TCS (Tata Consultancy Services) would earlier hire only M Tech holders from IITs. But the decision to start recruiting graduates changed the technical education landscape. Everyone wanted an engineering degree,” he adds.

The boom, however, ended in a problem of plenty.

Trainees at the Yogeshwar Dutt Wrestling Academy in Bali, Sonepat. Until last year, this was the mechanical engineering workshop of Bhagwan Parshuram College of Engineering. (Express photo: Ritika Chopra)

Trainees at the Yogeshwar Dutt Wrestling Academy in Bali, Sonepat. Until last year, this was the mechanical engineering workshop of Bhagwan Parshuram College of Engineering. (Express photo: Ritika Chopra)Alarm bells first went off about 15 years ago, in the shape of the U. R. Rao Committee report of 2003. Rao, former chairman of the Indian Space Research Organisation, had been tasked by the NDA-1 government to review AICTE’s performance.

The report had observed that the pace of expansion of technical education was unsustainable and that the explosion in the number of private institutions was fuelled more by speculative rather than real demand. “Barring some exceptions, there is scant regard for maintenance of standards,” the five-member panel said in its report.

To alleviate this “serious situation”, the committee suggested a five-year moratorium on all approvals for undergraduate technical institutions in states where the student intake exceeded the then national average of 150 seats per million population. This figure was 1,047 for the southern states, 486 in the west, 131 in the east and 102 in the north. (Currently, the national average of BE/B Tech intake, alone, is 1,286 seats per million population.)

However, Rao’s recommendation was never acted upon. Indeed, the reverse happened. According to AICTE data, 2008-9 witnessed an increase of almost 30% in engineering intake over the previous year—the highest in a single year since 2001—with over 700 new institutes being approved. Many point out that it coincided with a period when AICTE was rocked by allegations of rampant corruption. That year, the CBI caught then AICTE member-secretary K. Narayan Rao accepting a bribe from the owner of an engineering college in Andhra Pradesh. The incident eventually led to the suspension of then AICTE chairman R. A. Yadav. The CBI registered three cases against him, but did not chargesheet him.

The effects of this indiscriminate expansion in the sector were probably first felt after the global economic crisis of 2008, when growth slowed in the US and Europe, the main markets for IT companies.

Interviews with institute heads and students reveal that shrinking jobs, exacerbated by low employability of graduates, took the sheen off engineering. An immediate fallout of this was a drop in campus placements. In 2016-17, only 40% of B Tech graduates got placements, HRD Minister Prakash Javadekar told Rajya Sabha earlier this year.

Experts also point to a shrinking economy to explain the problem, with job losses across both old and new economy sectors—from textile to capital goods, banking to IT, startups to energy.

“The economy is in a bit of a stationary mode. Industries are not making any investments and so there aren’t enough engineering jobs in the market at present,” says former IIT-Kanpur director Sanjay Dhande.

An engineering degree in this climate offers little return on investment.

We had 60 students of mechanical engineering in the last batch (of 115) that graduated in 2016. Where you now see blue wrestling mats were several lathe machines

— S. K. Bhardwaj

“A student in a private engineering college spends about Rs.6 lakh on his course over four years. However, once they graduate, they are offered jobs that pay as little as Rs.10,000 a month. So why would he or she want to invest in an engineering degree?” says Vinod Choudhury, head of Vishveswarya Institute of Technology in Ghaziabad, when asked about seats going vacant. The institute, set up in 2007, had almost 90% of its B Tech seats vacant in 2016-17.

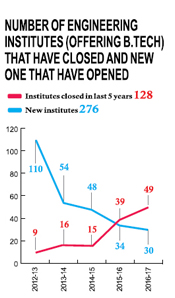

However, a slow consolidation has begun. While the number of new engineering institutes is at an all-time low (30 last year), the number of closed colleges—49—is a new record. The B E/B Tech and M Tech intake is also shrinking steadily—from 19 lakh seats in 2014-15 to 16.5 lakh this year.

M. A. Anandkrishan, an educationist who served as chairman of IIT-Kanpur for almost a decade, says he is not happy with this pace of consolidation. “(Waiting for colleges to turn unviable before shutting them) is a long and painful process and the students caught in this churn are the biggest losers. AICTE should impose a moratorium on new approvals.”

S. S. Mantha, who took over as AICTE chief in 2010, is against this approach. “It’s not tenable. In 2012, we tried to impose a moratorium but couldn’t as the Constitution allows everyone to practise the profession of their choice. How can the regulator stop them?”

After 2012, the AICTE is making yet another attempt to restrict approvals for new institutes. In a letter sent out earlier this year to all state governments, the AICTE said they could apply for a moratorium, provided they backed up their demand with a ‘perspective plan’—that is, map the current situation of industry, jobs and total seats in education, and use that to predict the demand for engineers.

Will this new plan consolidate the sector and cut down on ghost campuses? For now, the answer is up in the air, much like the dust that hangs over the wrestling arena at the Sonepat college.

(This article was originally published in The Indian Express. It is an Express Investigation - Part I: Why an undergraduate engineering degree in India is rapidly losing value—and currency)

Dr (Col.) A. Balasubramanian