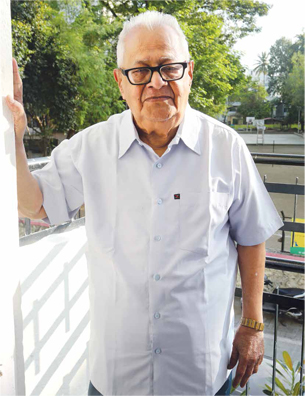

Dr P. C. Shejwalkar is known as the Father of Management Education in Maharashtra. What is less known is that he strived to be an entrepreneur and educationist since the tender age of sixteen.

Corporate Citizen walks along with him on the occasion of a major milestone in his life - his 90th birthday. We walk him down memory lane to find out the life, struggles, successes, love and joy of young Shejwalkar that carved out within him a master visionary educationist who pioneered management education in Maharashtra

The essence of my life is not always to conquer but to fight well; not to triumph but to struggle. I have struggled my entire life but with the difference that I always emrged successful, though slowly - one step ahead, each time

- Dr P. C. Shejwalkar

Dr P. C. Shejwalkar turned 90 on 16th January, 2017. He is unarguably the Father of Management Education in Maharashtra. At a time when management education was unheard of in Maharashtra in the 1970s, Dr Shejwalkar persuaded the University of Pune to launch a full time, post-graduate course and thereafter founded the prestigious Institute of Management Development and Research (IMDR). He was treading an unknown territory when he made IMDR an autonomous institute, inspiring several others to follow suit. Shejwalkar stands tall in the educational field for his innovation, enterprise and relentless pursuit of excellence.

After his long stint at IMDR—which is synonymous with his name—he is presently the Founder Director of the Institute of Management Education (IME) which he established after his retirement in 1989. People retire between 58 and 65 years of age. They keep harping on the leisurely time they now deserve but not Dr Shejwalkar. At the ripe young age of 90, he is physically present at IME office, sharp at 11 am He goes home for lunch break, after which he is back again in office at 4 pm until 7 pm. Thereafter, he goes back home where people come to meet him. Or else, he is speaking at some function in the evening, where he is invited as a chief guest, and such invites are in plenty.

His zest for life has not ceased. Instead, with childlike passion, he yearns to improve the educational sphere through his writings, speeches and correspondence with the powers-that-be. He describes his work as “enjoyment’’ and is therefore hardly stressed, he says. He is presently penning a book on people who inspired him in his life. He resides on the first floor of his bungalow and walks up and down, twice a day, despite bad knees. He is so involved with those around him that he feels the pain and joy of one and all. His inspiring story should shake all of us from negativity to positivity; from hate to love; from pain to joy and boredom to the blessings of all that we possess but don’t recognise. Read on…

Dr Shejwalkar as a bright young boy

Dr Shejwalkar as a bright young boyI was the youngest child in my family. My father was just an ordinary station master and his salary was not much, with no pension. By the time I finished my matric examination in 1945, he had retired. Instead of asking my father to bear the burden of my college fees and other expenses of commuting daily from my home in Thane to Sydenham College in Churchgate, I thought I should find my own ways to finance myself. I scored excellent marks in matric which is 86%—in those days it was difficult to score so high. I was fortunate to have got admission in Sydenham College, which was a prestigious educational institution and the first ever commerce college of India, started in the 1930s. Professors teaching there were selected from the scholarly Indian Education Service (IES) category.

With wife Usha and daughter Susham

With wife Usha and daughter SushamI was just 16 years old when I began my college education. I felt that I must earn. I started selling some small products in the local trains from Thane to V T (now renamed CST) station. I used to sell scented supari which was very popular in those days. During Diwali time, I would sell utna and firecrackers. However, soon I realised that selling in local trains was not permitted; I used to be regularly asked by the ticket collector to get down from the train.

However, I didn’t give up. I thought, let me go from hotel to hotel to sell these products and I really started doing that. Here, I got a ringside view of the socialist system, social values, and social way of thinking. In some hotels, when they saw a young boy of 16 years, so enterprising, they cheered me, welcomed me and gave me a cup of tea too. However, there were other hoteliers who literally drove me out and asked me not to come again, ever. This was a unique experience for me. Also, entrepreneurship is something that was alien to Maharashtrians those days; they were afraid to enter into it. Although I wanted to take up teaching as a profession, entrepreneurship in education was very much on my mind though I did not know the path to it those days.

“I used to also work as an enumerator at the Bombay Corporation during election time. I had to go from house to house to conduct a survey. Here I found some of the well-dressed people in good homes being very snobbish, whereas if I went to a chawl where workers resided, they were kind-hearted”

In those days I used to earn `200 per month which was a good source of income for me. At that time a haircut would cost four annas and a cinema ticket was available for six annas. Besides, I would also spend on home expenses. My father didn’t expect anything from me, but was appreciative of my efforts and ambition to earn while learning.

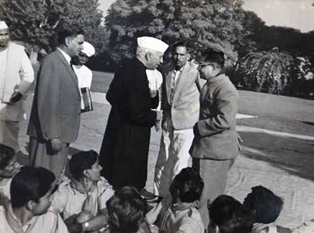

Dr Shejwalkar made his mark as an educationist at a

young age. Young Dr Shejwalkar with Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru

Dr Shejwalkar made his mark as an educationist at a

young age. Young Dr Shejwalkar with Pandit Jawaharlal NehruI used to start from my house in Thane at 9 am and reach Sydenham College in Churchgate at 11 am sharp. After college would get over at 3 pm, I used to go from hotel to hotel, selling scented supari, until 8 pm. After that, I used to serve as a night teacher in one of the Marathi night schools in Thane, teaching slum-dwelldwell-ers’ children, before I finally reached home. There I got another insight into the abysmal poverty that existed, where children didn’t have proper clothes to wear, would not get to have their bath regularly, but they were hungry for education. I felt very passionate about teaching such children who wanted to come out of their dismal circumstances through education. The guardians of the children too were very happy and were in fact curious to know more about me. So, five of them invited me to their home one evening. I obliged and went to one of their homes, which was a small hut. They were appreciative of my teaching at the night school. Grandmother of a student who welcomed me said, “I don’t have a bouquet of flowers to welcome you but I give you this incense stick,’’ and then she made a nice cup of tea for me. I was intrigued as to how she managed to get such a good quality cup. I was stunned to find out that she had hired the cups for me. I was truly overwhelmed. I realised that though these people are poor, they are large-hearted.

I used to also work as an enumerator at the Bombay Municipal Corporation during election time. I had to go from house to house to conduct a survey. Here I found some of the well-dressed people in good homes being very snobbish, whereas if I went to a chawl where workers resided, they were kind-hearted. High-class people don’t give any value to those who do mundane jobs, while below-poverty-line workers, despite their poverty, try to be good citizens.

“In Mumbai local trains which ran from Thane to CST, I used to sell scented supari which was very popular in those days. In Diwali I would sell utna and firecrackers”

I got a first class in B Com. After my graduation, my first job was in a government day school in Thane’s B. J. High School of Commerce. They wanted someone with a commerce background. The salary for a teacher in those days was Rs.70 per month, but because I had secured a first class in B Com, they offered me Rs.95 per month. I took up the job and simultaneously pursued my post-graduation.

By the time I finished my post-graduation, there was an opportunity to become a lecturer in a college. There were very few commerce colleges those days, unlike today. One was in Mumbai and the other was the BMCC College in Pune which had just started. I desired to be in Pune and so applied for the job of a lecturer in BMCC. The Principal was kind enough; he said there was no vacancy at the moment but I should leave my biodata with him and he would contact me in case of a vacancy.

So, I applied at J. G. College of Commerce in Hubli, as they were in search of good teachers —who were scarce those days. Apart from my salary, they gave me a free residential apartment and free meals because they wanted me to serve there permanently. It was a good college. The Principal was very kind and I enjoyed my tenure there. But as the year came to an end, the Principal said that he wanted me to sign a bond for three years. I asked why? He said, people like you who hail from Mumbai and Pune run away the moment you get a job in Pune or Mumbai. I declined to sign the bond as my aim was to come to Pune for post-graduate research work. I was inspired by a renowned scholar, Dr Dhananjay Gadgil and wanted to do a PhD. Then another job came my way—it was from Ahmedabad’s H.M College of Commerce. I served for one year and I enjoyed teaching there too. By then I was 22 years old and was teaching as Assistant Professor, with a salary of Rs.190. This was enough for me to live a comfortable life in a city like Ahmedabad.

BMCC yet had no vacancies but it was my dream to teach in Pune. However, when I once again spoke to the Principal of the college, he said my placement would be confirmed the next academic year. He did confirm. He wrote to me saying, “You are appointed, come immediately”. However, while posting my letter of appointment, he forgot to mention the name of the city. So, the letter travelled for two months before I received it. I hurriedly went to Pune to meet the Principal but he apologised, saying, since I did not reply, they had already appointed someone else, but for one year only. When he came to know that I had come all the way from Ahmedabad to meet him, he offered his home to stay over, saying that only he and his wife lived in his official bungalow.

Finally, in 1954 I joined BMCC as a lecturer with a salary of Rs.210. This was the start of my career in Pune. I had hired an accommodation for Rs.60 per month at Hirabag, Off Tilak Road. I purchased a bicycle for commuting to and fro college. We had to teach in two shifts—morning as well as evening. So, I would come back again after lunch. Life was a struggle, but I had made up my mind to work hard. In 1956, I told the Principal that I wanted to register my name for PhD. I approached Gadgil, who was the chairman of the Selection Committee. He welcomed my request and asked me to work under my Principal, T. N. Joshi. So, I started working as a research student under my own Principal, so my interaction with him increased.

I took the subject of railway finances for my PhD. Why railway finances? Because I was very interested in the subject. I knew the names of all the Mumbai local train stations consecutively by heart. People used to say, why don’t you work in the railways if you are so interested, but I used to tell them there was no teaching job there and I was not interested in administration. Here also my hard work did not end.

I used to visit the Sydenham College library for my research inputs. I used to also take tuitions in the evening as I needed more money. It was quite a struggle.

In 1958, I submitted the thesis after six months of research. Both my examiners were foreigners, so I was tense. One of them was from America—he was the chairman of the Railway Board those days and the other was the former Chairman of the Railway Board of Malaysia, after retirement.

After submitting my thesis, it took six months for the result. I was happy that I secured my PhD and started taking more active part in cultural activities and in giving lectures. I used to also write articles in local newspapers. My wife supported me immensely on all fronts.

After I finished my M Com in Siddharth College, started by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar in 1945, I applied for a lecturer’s job and I was selected for the interview.

To my great surprise, it was Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar himself taking our interviews in his capacity as the chairman of the committee. I was rather tense, wondering as to what kind of questions he would ask. He did ask some rather difficult questions, which I tried to answer. Fortunately, I was selected.

Then, Babasaheb Ambedkar asked me whether I knew that the college was meant for the backward category for those who wanted to serve the country. He asked me as to what I could do for the college apart from teaching? I said, Sir, whatever you tell me to do. Will you do social work? I said, yes Sir—tell me what kind of social work. And then he stumped me by asking whether I was willing to marry a girl from another caste. I promptly said yes, why not? He prodded further— will you marry outside your community? I said, “Yes Sir, why not? I am a forward-thinking young boy”. I thought he was pulling my leg, but then the head clerk took me to the girl’s house, which was in the outskirts of Mumbai. She was good-looking and cultured, but since I was only selected for the post of a lecturer and not yet got the job, I decided not to plunge into marriage so soon.

Thereafter, my uncle took up the responsibility of finding a bride for me and I met my present wife, Usha. She was seventeen and a half years old and I was 22 years old. This is how I married this girl, 66 years back. Whatever be the strange request of Dr Ambedkar, I was so fortunate to be interviewed by this great man. I wish I had recorded that interview. I got married in 1951 before I took up a job in Hubli.

“Today’s students are lucky and happy, because they are being provided all the facilities. A school going kid gets a transport, mobile, computer, just everything. Eight and ninth standard kids get to use the mobile and they can communicate so much”

Sushama Keskar is my only daughter; she is 65 years old. She is also an educationist and an academic scholar. She did her B Com, M Com and MSW. She completed her PhD and was the Principal of SNDT College, Pune for six years, before she retired recently.

My home is a modest bungalow in Deccan Gymkhana area. It is thanks to the books I wrote that I earned money to build a house. I first built the ground floor for Rs.69,000. At that time I bought the land for Rs.3.5 per sq ft., and the total area was 3,700 sq ft. Today, it is Rs.15,000 per sq ft. After some years, I built the first floor for my son-in-law. He is also in the educational field. He was the Principal of Dr P. D. Patil University. They have two sons—both of them are in the USA. I have two great-grandchildren.

Today’s students are lucky and happy, because they are being provided all the facilities. A school going kid gets transport, mobile, computer, just everything. Eight and ninth standard kids have access to the mobile which allows them to create and communicate so much. The sky is the limit for them. My great-grandson who is in America is now 10 years old. He uses the mobile and talks with us on Skype. He cannot speak in Marathi; he talks fluently in English.

In my personal opinion, we were required to work hard. Teachers were very strict. Today I find that they have changed the technique: a teacher does not get after the students and does not punish them. Young teachers are effiefficient, students are knowledgeable—they learn from their surroundings. Earlier, this was not the scene, and teachers were also fewer in numbers. My challenges were small. Today’s challenge is in a fiercely competitive world. The problem is that every year one crore people come into the employment market. The spread of education has increased but no one is bothered to see whether they have skill-oriented education or not. For example, everybody can use a computer, but how many can do photography? There is a huge demand for skill-oriented people.

I have never considered wealth in terms of money. My relationship with my well-wishers, friends and relatives constitute my wealth. Small, innocent kids, with a smiling face are also a part of my wealth.

I feel healthy and refreshed in the morning, after my exercises. I maintain health by controlling my diet and keeping myself as much as possible, away from smoking and drinking. I have bhakri with milk for breakfast and fruits for lunch. Occasionally I indulge in lunch if any of my favourite dish is cooked. After I turned 85, I’ve cut down on my supper and eating out.

The essence of my life is not always to conquer, but to fight well; not to triumph but to struggle. I have struggled my entire life but with the difference that I always emerged successful, though slowly—one step ahead, every time.

Sixty-six years of marital bliss has much to do with sharing life’s struggles together, adjusting with each other and standing by solidly with a spouse who has always been on the go, to bring in quality management education to the next gen. Meet the adorable couple, Usha and Dr P. C. Shejwalkar, the latter confessing that it was his better half who helped him move forward, by keeping peace and harmony at home

Married for 66 years, Usha and Dr P. C. Shejwalkar portray the bl i ss and contentment that emanates from a life of togetherness that has witnessed struggles and hardships, but with a never-give-up attitude. It is on this formidable foundation that they have earned success, happiness and marital bliss. The very charming and dignified Sushama Keskar, their only daughter and herself a well-acclaimed educationist portrays the scholarly and cultured upbringing that she has had.

In fact, the MBA bug runs in the entire family. Their son-in-law, Dr Anil Keskar, presently, Advisor, Management Studies, Dr. D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth is the former HOD of PUMBA and former Dean, Academics of Symbiosis International University. Their children, Amarnath and Ambika have pursued MBA after their graduation. Both of them, along with their spouses, reside in the USA.

Dr Shejwalkar’s grandson, Amarnath with granddaughter-in-law Dr Shruti, granddaughter Ambika and grandson-in-law Harshad Khurjekar and great-grandsons Amogh and Aditya

Dr Shejwalkar’s grandson, Amarnath with granddaughter-in-law Dr Shruti, granddaughter Ambika and grandson-in-law Harshad Khurjekar and great-grandsons Amogh and AdityaUsha Shejwalkar is extremely talented—a vocalist of repute, she was for many years an artiste at All India Radio; she also has several albums to her credit. Besides, playing table tennis was her passion. However, these qualities are not as well-known, because giving unflinching support to her husband’s passion for MBA education scored over everything else. Says she, “Giving him cooperation in whatever he did has been the main aim in my life.’’ Dr Shejwalkar quickly asserts, “It is true, she has supported me extremely nicely. And she has done so relentlessly, without complaining,. The secret of my being able to work even at this age, for hours together, is because there is peace and tranquillity when I come back home.’’

Usha Shejwalkar though states candidly that the secret of their happy marriage is because she has unconditionally submitted to him. Says she, “I was 17 years when I got married so did not have much maturity. However, I understood within two to three months of our marriage that he was a very strict person and did not like being opposed. So I decided to keep saying ‘yes’ to whatever he said.’’ Dr Shejwalkar butts in, “Oh, that’s an utter lie. When did I oppose you?’’ And then they laugh. On a more serious note, she says, “He has worked very hard to become successful in his life. He did his PhD at the age of 26. At that time we were living in just one room and struggled in life to come to this stage of contentment and happiness.’’

So, what according to her, is the secret of a happy marriage? Says Usha Shejwalkar, “if you oppose, then happiness disrupts. However, I must add that he encouraged and supported me in my singing talent.’’

Son-in-law, Anil Keskar

Son-in-law, Anil KeskarAnother admirable decision that the Shejwalkars took was regarding family planning, “At a time when having a single child by choice was unheard of, I told him that we should have only one child, be it a boy or a girl. He stood by me in this decision and I really appreciate him for that.’’ As for today’s couples who are not as tolerant of each other as the earlier generation, she feels, “girls today have the freedom to express their opinion and make a choice, which I think is good. But, they should not go to the extreme. They must try to be compatible with each other.’’ Adds Dr Shejwalkar, “I don’t blame women—they were suppressed by the husband and their family members for decades. Now they are educated and independent, so they have their say and rightfully raise their voice. It is true that divorces are on the rise— that’s because of intolerance towards each other. Mutual adjustment is necessary for a successful marriage.’’

What is the secret of their fitness? Says Mrs Shejwalkar, “I used to play table tennis a lot in my earlier years. We would both go for walks together too. Nowadays we find it difficult to go for long walks. And we eat in moderation.’’

Like they say, ‘Happy is the man who finds a true friend, and far happier is he who finds that true friend in his wife.’ It aptly fits Dr Shejwalkar.

“At a time when having a single child by choice was unheard of, I told him that we should have only one child, be it a boy or a girl. He stood by me in this decision and I really appreciate him for that”

— Usha Shejwalkar

Sushama Keskar

Sushama KeskarIt is difficult to talk about your own family members, but my memories of my father is that he was always busy with his work and study. At times, he didn’t spend much time with his family. Despite that, I remember we had a bicycle, and he used to take me on the small seat (in front), to his friends’ houses. He used to also take me to Sarasbaug once in a while. Although I was the only child, I was raised by my parents just like other children.

The environment in the house was conducive to studies as there used to be lots of books at home, mostly on subjects my father studied or taught. I used to read them with great interest. That’s how I was inspired to take up the same profession as my father’s. I chose Commerce and later pursued MMS (Master of Management Science) and stood first in the University of Pune. I then pursued my PhD in Management. I worked at the SNDT College of Commerce from 1980 and retired as Principal in 2014. After retirement I did a course in Psychology and I am a part of the Vishakha Committee in several corporate entities.

Both my children have also done MBA from the Symbiosis Institute of Business Management. My son is a software professional. My daughter who completed her engineering and MBA from India, pursued MS in the USA. She is into jewellery designing. My son has two children—the elder one, Amogh, is 10 years old and the younger one, Aditya, is 5 years old. My daughter-in-law, Shruti is a doctor of Naturopathy, and also teaches yoga.

By Vinita Deshmukh