In the Air Force, it was more relaxed. But I also realised people were not open to work. I told them, how does it matter whether you’re a senior or junior? Whatever you’re doing, you’re doing it for your own people and comfort”

— Molina Tipnis

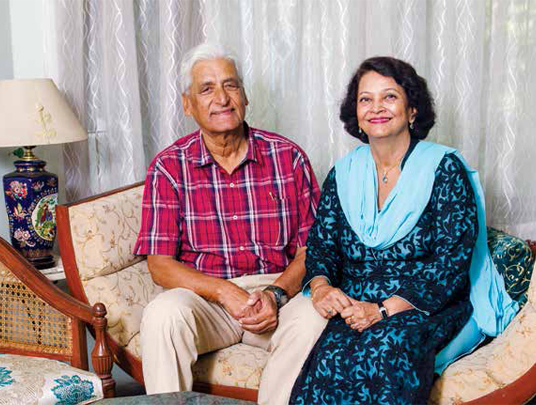

Was it fate or destiny? Was it love-at-first-sight? Even they didn’t know. But when Anil and Molina met each other for the first time, they felt, the entire universe seemed conspiring to help them discover each other. Otherwise, there was absolutely no reason for them to even meet, and later remarry. For, both were happy with their respective spouses in their first marriages and life would have continued the same way had tragedy not struck them midways and turned their lives upside down. While Molina, a dietician from Nagpur, lost her first husband because he got seriously ill due to his unusually long posting on the high-altitude battlefield of Indo-China border in Sikkim, Anil’s first wife left him as her kidneys stopped functioning prematurely. Both were just not prepared to face the untimely exit of their partners. While most people fail to take up the challenges in the changed circumstances, Anil-Molina triumphed. Corporate Citizen spoke to this dynamic duo to know how they faced it all and how they’re still passionate, intimate, inspiring and truly adore one another. Excerpts:

- Molina Tipnis

Molina: He was also Anil (smiles). Major Anil Thackrey. He was our neighbours’ son in Nagpur who proposed and married me when he was a Lieutenant. He became a Captain soon and then Major in the Army. We had a ten-year-long marriage. He was in the Artillery and on a higher-altitude posting in Sikkim where he stayed for over three years which is rare because people generally get such postings for one-and-a-half years only. But they kept shifting him from one unit to another, causing him severe breathing problems because of the lack of oxygen and uncongenial weather.

No. As soon as we got married, he was sent to Sikkim, a non-family station. For three years, I was with my in-laws in Pune. My son was born there. When he was 6-7 months old, I joined Anil in Hyderabad. But within two months, he was posted to Dhrangadhra (Gujarat) where he had his first heart attack. When he died in 1983, my son was only eight years old.

I came down to Pune to give my son a home at my in-laws’ place. My father who retired from a reputed pharmaceutical company in Nagpur also decided to settle down in Pune. He took a bigger flat and we shifted there. Getting admission for my son in the fourth standard in Pune was very difficult. Karnataka High School said that if I took up a teaching job, they would give him admission. For one year, I took that up. My pension was Rs.400, which was enough for his school fees. I had no other means. I decided to start something where I could earn more.

a boutique. I took coaching from a tailor, then took a garage in a nice area and converted it into a boutique. There were two to three colleges nearby, so a young crowd would gather there.

His aunt retired and settled down in Pune. She was in contact with my parents and enquired if I’d be interested in a second marriage. They told her I was not ready. I too felt, who could guarantee that the second marriage would be successful, and now that I had settled, why should I disturb my child? But she insisted, “Let them meet. We won’t say anything.” He had come to Mumbai to collect his luggage which came from France. His aunt called him to Pune for a day and that’s how we met.

Yes I did, but I was in a different mindset when I met him and two of his daughters. The next time he said, bring your son. We met again. We had lunch together. My son didn’t realise what was happening. I also didn’t know how his daughters would react. I thought it would be good for my son, because he was exposed to a services’ life and was feeling like a misfit in Pune’s civilian life.

We had always taught him to wish elders, but whenever he would do so, people would look the other way. He would complain, why do you teach me something which people don’t even accept? Similarly, he’d wear shoes to go down, but everyone else would be in slippers. He’d speak in English, but everybody spoke in Marathi. I thought he’d be happy if he went back into the services atmosphere. That’s why I agreed to meet him again with my son.

When I told him about marriage, he wasn’t happy. He said, why do you need him? I explained that when he grew up, he would go away. Then who would look after me? But he thought that I was thinking on those lines because of finances. “I won’t ask you for anything, but don’t remarry.” Then I said, “Okay, you meet him. If you like him, then only I’ll remarry.”

When Anil came, he took us out for dinner. My son was very interested in astronomy. When Anil started talking about the stars, galaxies and all that, my son heard him attentively and there was an immediate bonding between them. Thereafter there was no going back. He was happy. In a month’s time, we got married. Post-marriage also, when Anil would come back from office, he would have all his questions ready—which is this aircraft, which is that and so on, because he didn’t know anything about the Air Force.

For one year, I was in a shell. Then I realised, if I sit like this, the children would not have any family life. As it is, they were without their mother. So I tried to get over it. In those four months, my son had developed a great bonding with the girls. He would keep them busy with his questions. Soon, they started introducing him as their brother. Sometimes I feel his role was only to bring us together. When he left, the girls also began empathising with me.

They were all grown up. The eldest was 20, and had got married six months before ours. The next, studying Veterinary Science in Mumbai, was 18 and a half, and the youngest, doing English (Honours) in Delhi, was 17, whereas my son was 12 years old. When their father told them about our marriage, they said, go ahead but remember, you’re not bringing a mother for us. You’re marrying for yourself. That was very clear. They didn’t call me mamma, but treated me like a friend and called me Molina, though they felt my motherly feelings gradually. Now they don’t introduce me as anything but their mother and I’m the favourite naani to all my grandchildren.

There was no entry for girls in the Air Force then. If they had the option to fly fighter planes, my younger one would have definitely joined it.

Actually, when I was with the Army, I had seen how things were done. But in the Air Force, it was more relaxed. But I also realised people were not open to work. I told them, how does it matter whether you’re a senior or junior? Whatever you’re doing, you’re doing it for your own people and comfort. So I began doing things myself —flower arrangements on tables, rangolis, etc. When the station commanders’ wives visited us for the commanders’ conference and saw me drawing rangolis, they’d ask, “Oh Ma’am, why are you doing it? and I’d say, ‘So what?’” Gradually, the work culture began changing. Similarly, as president of AFWWA, though I was somewhat strict over the welfare activities, I encouraged people to open up and do things themselves.

Soon after our marriage, there was an accident and they made Anil the commanding officer for the court of enquiry. So he dropped us off at Gwalior and within two days left for Delhi and other places for a month. We were new and I didn’t know anyone on the station. I had no clue as to how an Air Force station runs. I had not yet shifted my bank accounts and was still shy to ask him for money. When he left, he also wasn’t used to having a wife in the house. So he forgot to give me any money and left. Whatever little I had, I barely managed with that, though later when he realised it, he sent an officer to help me. But, my very first month tested me (laughs)!

They were surprised. Who gets married at this age, they would say, though privately. But the senior ladies treated me like a daughter and took me under their wings and said, “Okay, she’s new, so what? We’ll tell her how to do it”.

"Happiness lies within you. There is no destination for happiness. She’s never worn a uniform but her self-discipline is as high as that of a military person. I greatly believe in self-discipline and self-regulation. I believe each one of us is in charge of our own destiny”

- Anil Tipnis

Somehow unfortunate things kept happening with us. First, I lost my son, then my younger daughter, and her husband. She married in December 1992 and went with her husband to Pittsburgh, US, for him to complete his MBA, but within a year, they had a car accident and he died. She came back. She always took a cue from me. Since I stayed with my in-laws, she also did so, and then educated herself further. She did her Masters in French and became a qualified French teacher, though she doesn’t teach French anymore.

She is in Mumbai. She got remarried; she had no issues when this accident happened. But she had very good relations with her in-laws. Then her friends introduced her to this boy, Varun Batra, an investment banker and a gem of a person who was with Citibank. He has now left that job and opened an investment banking company with friends. They’re doing well. She has a son and a daughter.

The middle one, the Veterinary Surgeon, started flying with Cathay Pacific and then got married to an Australian guy. They have a furniture business in Melbourne. She’s got a son. The eldest one is in the UK. She’s also a banker. Her first husband was an Indian, born and brought up in UK, but after 14 years of marriage, they separated. Now she’s got a partner who’s a British army officer and two sons. They’re doing well.

Respecting and giving space to each other and taking every decision with due consideration for each other.

(Laughs) He always gets the better of it.

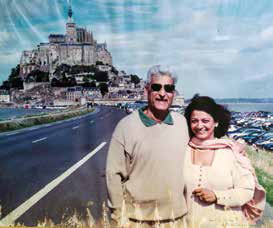

We both love to go out and see new places. We don’t get tired or hassled by air travel or driving. We enjoy it. We both love exploring new things.

We’ve been on a few cruises. We have seen many countries including France, Italy, UK, Israel, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, South Africa, Kenya, Brazil and so on.

I also went to China as the serving Chief. In India, we’ve also been to many sanctuaries including Ranthambore, Bharatpur, Kanha, Govindgadh Tiger Sanctury in Rewa, Kaziranga and the rest. We also took our grandchildren to different AF stations and they’re quite impressed.

Anil: Happiness lies within you. There is no destination happiness. In the good times and the bad times, you’ll find a way. You’ll find a solution. We also need to raise our standards. (Pointing to Mrs Tipnis) She’s never worn a uniform but her self-discipline is as high as that of a military person. I greatly believe in self-discipline and self-regulation. I believe each one of us is in charge of our own destiny.

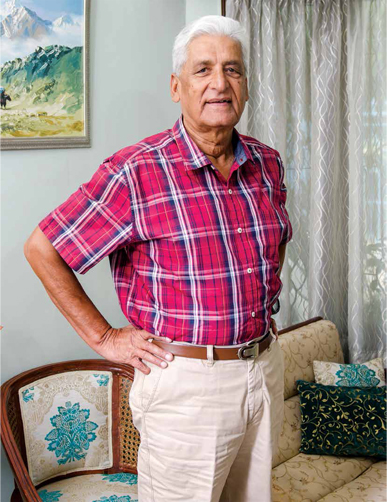

Why do some military leaders rise to greatness while others falter in their long and demanding careers? Why do some enjoy enormous respect even decades after their retirement while others tend to get ignored? Military historians say, it depends on how they play their role during the war or natural disasters. Air Chief Marshal, Anil Yashwant Tipnis (Retd.) is one such who belongs to the former category. Though he retired on 31st December 2001, after heading the Indian Air Force (IAF) for three years as its 18th Chief of Air Staff; 15 years later, he continues be remembered for his dynamic leadership and tactical genius during the 60-daylong Kargil War in 1999 not only by serving and veteran air-warriors, but also by people at large. Known for his moral uprightness, personal courage and careful planning, Tipnis has rarely talked about how he engineered tactical surprise during Operation Safed Sagar, codename for IAF’s strike, to provide potent support to the ground troops of Indian Army’s Operation Vijay. What was the inside story of IAF’s deadly air strikes which eventually led to not only recapturing of the lost posts but also evicted Pakistan Army’s occupation of Indian forward posts in the Kargil- Dras-Batalik sector? In a trip down memory lane at his Gurgaon residence, the very fit, 77-year-old retired air chief, with his charming wife Molina, talk candidly and patiently about his love for flying and how he faced challenges of his times

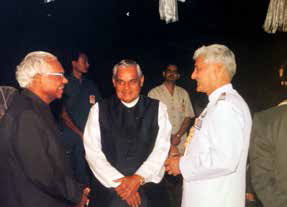

Receiving the US Commander-in-Chief (Pacific Naval Command) in New Delhi

Receiving the US Commander-in-Chief (Pacific Naval Command) in New Delhi

My urge to fly was ignited at age three. My father, a civil engineer, working with the Irrigation Department of pre-Independence Central Provinces and Berar (now MP & Chhatisgarh), joined the army at the start of WW II; he served in Iraq till the end of the War. My mother stayed at Pune to take care of us five siblings and our paternal grandparents. My grandfather helped out with the weekly shopping, as well as by taking care of me, the family’s youngest. After the shopping, he and his friend would sit under the shade of tamarind trees at the base of Parvati, Pune’s famous temple on a hilltop. Often, yellow-coloured aircraft flew overhead; I marvelled at their aerial manoeuvres. On a couple of occasions the aircraft came so low that I found my heart pounding with anxiety; my wonder only grew and a vague wish to be ‘up there’ took root.

In 1950, near our house in Deolali, Army had based its Auster observation aircraft in an open field, making it possible to get close to them. The servicing crew allowed us to observe them at work, even allowing entry into the cockpit; feeling the controls and watching all the dials on the console gave me an inexpressible joy. Later, when we moved to Delhi, during vacations, I would sit at Palam airport for hours watching aircraft takeoff and land. I decided there was only one thing I wanted to be—a pilot! When my eldest brother joined the Navy and the next one the Army, my way to the Air Force was without any hindrance!

After an year at Deolali, as 1950 came to a close, father was posted to Delhi. Our pater, an ardent outdoor man, was impressed with the emphasis our school, Barnes, gave to sports and adventure activities; so, as we three brothers had also taken a fancy to the school, we stayed behind as resident students. Though I was not the brightest at academics (often being chided for being “a disgrace to the Tipnis family” and lagging “streets behind my brothers”), my five years at Barnes were most exciting and memorable. As my proficiency at English improved, my academic performance took an upturn, and the classroom was no more a dreaded place! Barnes, popularly referred to as the school-on-the hill, had a marvellous locale, with acres of open land, sports fields and swimming pools made out of a quarry and a blocked natural stream. Following the Senior Cambridge curricula, learning was more by application of mind than by rote. Anglo-Indian teachers were friendly, encouraging mentors to us in every aspect of broadening our world.

A co-educational school with mostly Anglo-Indian students, there was a fair sprinkling of Parsis, Muslims and Hindus with varied background, giving us a very open, cosmopolitan outlook to life. Over the weekends, boys were encouraged to go out on ‘rambling permits’, which gave us freedom of scouting around the beautiful surroundings of Deolali’s rural area.

"I still remember very vividly, my first launch in a glider; the thrill of being up in the air was absolutely exhilarating! It was superlatively exciting, a bit scary too, to suddenly find oneself up in the sky, all by oneself”

Air Chief with Air Force Commanders

Air Chief with Air Force CommandersThe NDA is a unique institution, where future of ficer-cadres of India’s three defence services jointly receive their initial military training over three years. As young boys are turned into military men, the first four terms, not only have a common academic syllabus, the cadets are also introduced to the characteristics of each service, so that they understand each other’s way of functioning. In the last two terms, academics break into two streams: technical and non-technical, the former getting to be science graduates and the latter in arts. Service training, at this stage, gets to be service-specific, cadets for the first time being formally trained for and recognised by their service.

I excelled at boxing and sailing, earning academy blues in both the sports. In third year, as I learnt about the principles of flight, airmanship, aero-engines, air-frames and the role of an air force, my interest in aviation grew by leaps and bounds. Familiarisation visits to the Air Force station at Pune had me becoming impatient to start flying training. I still remember very vividly, my first launch in a glider; the thrill of being up in the air was absolutely exhilarating! As gliding was just being introduced, it was in its nascent form, the syllabus was yet to be finalised. Some of us, who got to fly solo, were the envy of our course-mates. It was superlatively exciting, admittedly a bit scary too, to suddenly find oneself up in the sky, all by oneself. At the end of our training, it was a singular honour to be chosen to be the cadet to demonstrate gliding to parents and guests invited for our passing- out parade.

I passed out from NDA in December 1958 and reported to AFFC at Jodhpur, as the new year dawned. It was a remarkable change in every sens e : from the luxuriant greenery of Khadakvasla (NDA’s locale) to the dusty bowl of the Thar Desert; NDA was a national showpiece then, a must-visit for every foreign head of state, whereas the AFFC was a makeshift arrangement, a far cry from the present impressive facility at Hyderabad; NDA training was designed along Army’s rigid spit-and-polish approach, whereas the Air Force way came across as easy, if not laid back, on ground. But it was a different story in the air. Once in the cockpit, a pilot underwent a complete transformation: focused on the job at hand, meticulous in his checks and procedures, absolutely insistent on precision flying. It was not only a question of honing one’s psycho-motor skills, but also of acquisition of steadiness of nerve, situational awareness and calmness under sudden change of weather or failure of aircraft systems. One-year training at AFFC was split into two stages: basic and intermediate. As the nomenclatures indicate, basic training developed one’s psycho-motor coordination necessary to use aircraft controls to fly an aircraft. Intermediate training introduced fledgling pilots to fly without the benefit of external reference to the horizon; aerial navigation, formation flying, aerobatics, recovery from unintended attitude/manoeuvring of aircraft. The continuous upgrading of one’s skills was both a challenge and a daunting experience. Intensity of my fascination for flying grew with each new step.

With President K.R. Narayanan (left) and Prime Minister

Atal Bihari Vajpayee on Air Force Day, in New Delhi

With President K.R. Narayanan (left) and Prime Minister

Atal Bihari Vajpayee on Air Force Day, in New DelhiAt the end of our training at AFFC, we’re split into fighter and transport streams. One’s grading in flying and reflexes in aerial situations were the criterion for decision-making. As the mid ’50s had seen IAF’s WW II propeller-engined fighter fleet upgrade to jets, jets had an aura of frontier technology; so it was most thrilling to get selected for the Advanced Stage of Jet Training Wing at Hakimpet (Hyderabad). The HAL manufactured HT-2 trainer at basic stage which operated at sub-100 mph; on the radial-engined American Texan we had advanced to 200 mph. And, now the Vampire, with its jet engine, was pushing us beyond 300 knots. With no propeller in front, it was an eerie feeling to be floating in air without any apparent power plant. After we’d acquired proficiency on the Vampire, we’re finally introduced to the art of fighter flying in the appropriately named Applied Stage; no more “fun” flying, but learning to use an aircraft as a weapon’s platform. We performed advanced aerobatics, practiced tail-chase (following a hard manoeuvring aircraft); carried out tactical and battle formations; learnt the importance of visual lookout in tactical situations, particularly in aerial combat spotting a bogey (unidentified aircraft) before being spotted yourself was crucial, especially if the bogey turned out to be a ‘bandit’ (hostile/enemy aircraft). And carrying ordnance, cannons, rockets and bombs to become an aerial marksman. While donning of ‘wings’, the official appellation of a pilot, had to await the ceremony at the passing-out parade, we had started strutting around with the swagger of a pilot!

After consistently standing second at every stage of flying training, it was an overwhelming experience, to get to the top and receive the Majumdar Trophy (named after “Jumbo” Majumdar, IAF’s legendary flier) for the Best Pilot in jet flying training! After five long years of military and flying training, we’re ready to be inducted into frontline fighter squadrons of the IAF.

Air Chief and First Lady with the then President K.R. Narayanan (centre) and Vice President Krishan Kant (left) on Air Force Day, in New Delhi

Air Chief and First Lady with the then President K.R. Narayanan (centre) and Vice President Krishan Kant (left) on Air Force Day, in New DelhiThe British Hawker Hunter was IAF’s leading fighter aircraft at the start of the ’60s decade. I was lucky to be posted to 27 Squadron, the Flaming Arrows, one of IAF’s five Hunter squadrons, in Ambala. Hunters had a dual role—as an air defence interceptor and as a ground attack fighter. So, during training, I was exposed to the complete gamut of fighter aerial tactics and its role of destruction of enemy assets on ground—runways, aircraft, bridges, railway yards, dams, army tanks, guns, bunkers, ammunition depots—anything that could debilitate enemy’s fighting potential; but aerial combat is the ultimate valuation of a fighter pilot, for one’s flying prowess is pitted against another. For a young pilot in his early 20s, it was an intoxicating experience!

The debacle of 1962 against the Chinese was an enormous hit to the Indian psyche, particularly to the military. The positive outcome of the national shame was the realisation that the armed forces could not be neglected any longer. A huge upgrade, both in qualitative and quantitative terms, was undertaken with the help of the Soviets. In 1963, the first MiG-21 squadron, No. 28, was raised at Chandigarh, after seven pilots had been trained in USSR. On my 23rd birthday, I was among the first four pilots to join the unit for training in India.

After the 1965 Indo-Pak war, IAF expanded rapidly. Until then, there was only one MiG-21 squadron, but over the next few years, as Indian production surged forward, it became ubiquitous and equipped a total of 15 squadrons. Being a pioneer on the fleet, I found myself moving to a new raising with the aircraft. In less than an year, I became the senior flight commander on the MiG-21 training squadron and later in a squadron upgraded to its latest mark. In between, because of my MiG-21 expertise, and as a winner of the Norhona Trophy for best Pilot Attack Instructor, my services were loaned to the Iraqi Air Force for two-and-a-half years. Having qualified as a Fighter Combat Leader, bagging the Sword of Honour, I served on the staff of the Establishment responsible for developing IAF’s tactics and combat doctrines, as well for the training of senior pilots in combat and tactics. My first staff assignment at Air Headquarters, after graduating from the Defence Services Staff College, was as an inspector at the Directorate of Air Staff Inspection. This job afforded an opportunity to fly with and standardise all 15 MiG-21as well as the Hunter squadrons. I could also do my conversion onto the first Indian-designed and manufactured fighter, the HF-24 Marut. Having such a deep and varied experience of fighter flying, particularly so the MiG-21, it was but natural that my field flying career culminated with command of No. 23 Panther squadron, changing over from the Gnat to the latest mark of the 21. Commanding a fighter squadron is a coveted ambition of every fighter pilot; whatever comes later is bonus.

Although the one joins the military, are well aware of that preparing for a war is a life long pursuit; its reality hits you only when there is war-like situation. Until there are active operations, it’s the glamour and sagas of heroic valour of past heroes that one imagines himself to have been a part of, rather than of participating in operations yet to be faced. So when an opportunity arises, a true warrior is itching to go into operations. The first time that such a possibility arose was during the 1961—Goa Operations—that it’d be a short, one-way skirmish was a forgone conclusion, So, every fighter squadron hoped that it would be “the chosen one” to give the coup de grace to the Portuguese Rule in Goa. Naturally, most were disappointed; the one unit that, so to say, did get to fire in anger, found it more akin to training exercise, given the benign air situation.

With the detection of Chinese incursion into the Aksai Chin area of Ladakh, the two Hunter squadrons at Ambala, had done a few area familiarisation sorties. When some of our troops were lost to Chinese assaults and others withdrew, I found myself part of an eight-aircraft formation, loaded with rockets and cannons, standing-by at cockpit readiness, awaiting formal orders to start engines. After over an hour of staying strapped in aircraft, the station commander, who was glued to the phone in our operational dispersal, reluctantly gave a thumbsdown, indicating cancellation of the mission, much to the disappointment of all. There was never any call for air action thereafter.

No doubt the war would have taken a different turn, which way, has been speculated upon by many over a period of time. One thing is certain, Chinese People’s Liberation Army Air Force was in no position to operate effectively from their Tibetan bases; it would neither have been able to provide meaningful support to their ground troops, nor would it have offered any opposition to us. IAF’s initial effectiveness would have been slow, due to insufficient experience in the area; also, a few aircraft losses were inevitable, due to inadvertent mishandling of aircraft in the rarefied atmosphere of the highmountain ranges. But within a short time, IAF would have come to grips with the local conditions and adjusted its operations. With the IAF in support, our ground troops stood a far greater chance of thwarting the out numbering Chinese marauders. Political leadership had lost its nerve after the initial shock; it is also possible that the Air Force did not press for its use with conviction. At critical junctures, a nation’s leaders have to take well-considered chances, for there are rarely any forgone conclusions; this is what segregates the GREAT from the ordinary!

"If you are seeking riches or a life of comfort, the IAF is not the place for you. But if you desire a life full of challenges, whose accomplishment brings you enormous satisfaction. Then come, you have what it takes to be an air warrior!”

Given the conditions prevailing at that time, three years were not enough to reap the benefit of measures initiated to modernise and strengthen our armed forces. Pakistan, meanwhile, had gained enormously with its pacts with the US, and the quality of their military hardware had become superior to ours. Emboldened by India’s poor showing in 1962, they planned elaborately to militarily sever J&K from the rest of India. Their Operation Grand Slam to do so would have succeeded, had the IAF not used its vintage Vampires to stop the Pakistan armour from its diabolic plan. Pakistan Air Force’s unanticipated counteraction against our air bases caused disproportionate aircraft losses to us on ground. But our Army and Air Force regrouped quickly to turn the tide with their superior skills and leadership. While in terms of figures of aircraft losses, we didn’t stand well, in the ultimate analysis—we came out victorious by foiling Pakistan’s plan of taking over J&K by force. 28 Squadron’s MiG- 21s operated from Adampur and Pathankot to ensure safety of our strike forces returning after forays into Pakistan. We also carried out combat air patrols over Lahore and Kasur areas, challenging PAF to air combat on their territory, which they discreetly avoided. Only our squadron commander succeeded in downing a Sabre.

On a personal note, two incidents were of particular interest, the first during the war and the second soon after ceasefire came into effect: while coming back to Adampur after giving top cover to strike formations and their escorts returning to Pathankot, I realised from radio exchanges that one of the Gnat escorts, call sign Black 3, had not yet returned. As we approached our base, I was startled to hear a faint call from Black 3, requesting Adampur for a homing (heading direction for recovery). As there was no response from Adampur, there was a repeat request. As Adampur again failed to respond, I relayed the request, asking Adampur to convey the reading on its direction indicator with a voiceless transmission immediately after mine. This method succeeded in I being able to give Black 3 his homing of 120 degrees to Adampur; an extremely anxious Black 3 wanted a confirmation, which was given, exhorting the distressed pilot to follow it without hesitation. Before I could ensure that he followed the instruction, my leader ordered a change of radio channel in preparation for landing. I was unable to request my No. 1 to revert to the previous channel as there were far too many aircraft requesting priority for attention. On asking my leader why he’d changed channel while I was aiding a pilot needing assistance, he was thunderstruck that it was I who was in dialogue with Black 3! That evening Pakistan Radio announced that a Gnat had landed at its unmanned runway at Pasrur; the bearing of Adampur from Pasrur is the same as the homing given to Black 3!!

Even after the ceasefire, Pakistan’s ultra- high-level reconnaissance aircraft, the RB- 57, continued its attempts to sneak into Indian territory; only the MiG-21, with its ability for a dynamic zoom climb (converting extreme high speed into height in a very steep climb) had the ability to intercept the snooping aircraft at its operating altitude in excess of 60,000 feet. It was a cat-and-mouse game, the 57’s attempts to sneak in being foiled with the scrambling of a 21 from our side. But for an opportunity to do a non-routine exercise, one could have easily got bored with the whole process. So when I was scrambled this day, I was prepared for the oft-repeated process of being recalled after the controlling radar station was satisfied that the intruding aircraft had withdrawn to Pakistan territory. But lo and behold, the interception continued beyond the anticipated stage and I was directed to climb to 11 km (about 40,000 feet) and accelerate to 1.9 mach (1.9 times speed of sound). I was cautioned that I’d be crossing the international border, and ordered to make my missiles “hot” (ready to fire). As I attained the assigned height and speed, I was directed to zoom to 19 km (about 62,000 feet) and search for a target in my front 60-degree-cone. My scan moved to and from my aircraft radar to visual; but all I saw was a blank radar screen and a spotless azure blue sky. Suddenly, there was absolute radio silence and my requests for further directions went unheeded. I realised, I’d lost radio contact with the radar station and had little idea of my ground position. Luckily, my estimation of location was reasonably accurate and I was able to recover at Pathankot, but with nearly empty fuel tanks!

This was a personal disappointment as I didn’t get to participate in it. When War broke out, I was on deputation to the Iraqi Air Force and Air Headquarters didn’t feel the necessity to recall the 20-25 instructors in Iraq at that time. Reports coming in regularly from India conveyed a very high morale, as we’d trained and prepared well for a war that was inevitable; Pakistan, on the other hand, was in disarray with a very low state of morale.

The events leading to the Bangladesh War and the war itself, even today, stand as a testimony to the advantages of meticulous planning, patient buildup of assets, focused training, and most importantly, the synergistic effect of politico-military decision-making in concert and to the successful coordinated functioning of the three services, with absolute mutual confidence.

‘We both love to go out and see new places’

‘We both love to go out and see new places’Undoubtedly, it was an exciting experience with a most satisfying end result. Caught offguard, when Pakistanis moved into Indian Army’s forward posts along the LOC in the Kargil- Dras-Batalik sector, which for years, were routinely vacated at the onset of winter, the Army’s leadership was too embarrassed to reveal their professional faux pas to the government and was keen to recover the situation before the government got wind of it. In its anxiety to keep the situation under wraps, the Army failed to make a comprehensive assessment of the situation, and demanded armed helicopter support without mutual consultation or briefing. Air Headquarters did not find this approach in line with well-established laid-down procedure; at the very outset, it was also realised that given the high terrain, bereft of vegetation, helicopters were highly vulnerable to hostile action from the ground. It was also pointed out to Army Headquarters that use of air power opened the possibility of rapid escalation of air action from the other side, just as we had experienced in 1965 when Vampires were used against Pakistani armour; military prudence also required the Air Force to take the necessary precautionary steps; to do that, government clearance was inescapable. The air force position forced Army Headquarters, after considerable delay, to approach government for air support; but Army’s insistence on use of only helicopters persisted to the point of straining Army-Air Force working relations. Air Headquarters, going against its professional assessment, relented to maintain cohesion, but put a proviso that helicopters will operate in conjunction with fighters—a decision that proved to be crucial in the operation’s ultimate success.

If you are seeking riches or a life of comfort, the IAF is not the place for you. But if you desire a life full of challenges, whose accomplishment brings you enormous satisfaction; if you want lifelong unselfish friendships, if it is the ultimate thrill for you to pit your professional skills against an adversary with devilish intentions; if you want to be the man or woman, who, after you are gone, will be remembered as a “man or woman of worth, indeed!”, then come, you have what it takes to be an air warrior!

By Pradeep Mathur