The National Law University Delhi (NLUD) has risen to a premier position in law education in a short span of time, getting recognition for high-quality teaching and pioneering research. Its students stand out wherever they go, be it the judicial services, overseas institutions or the practice of law. This remarkable achievement has come about through deliberate thought and action. At the core of this effort stands its founder Vice Chancellor, Prof (Dr) Ranbir Singh

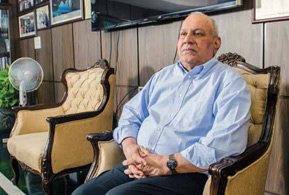

India’s capital is home to prestigious universities including the JNU, University of Delhi, IIT Delhi, AIIMS, Jamia Millia, NSD, IIFT and IGNOU. A recent addition to this list is the National Law University Delhi (NLUD), whose law graduates have brought accolades to their alma mater in a remarkably short span of time. They have repeatedly topped the exams of Delhi, Punjab and Haryana judicial services and civil services exam. Several, who graduated from here have joined the world’s top-ranking law schools like Oxford, Cambridge, Yale, Harvard and Stanford. To know what makes NLUD the most sought-after law school in the country, Corporate Citizen spoke to its founder Vice Chancellor, Prof (Dr) Ranbir Singh, who is considered to be an authority on Modern Jurisprudence. Excerpts:

I’m not very ambitious. I prefer working quietly. If you do a good job, its vibrations travel. You need not make publicity. That’s why you find NLUD is the least-publicised institution throughout the country. We openly say, please don't rank us. We don't believe in paid rankings. My rankings are my students. If my students do well, my faculty does well, why do I need any publication to rank me? They don't understand the institutions. How they can rank me?

UGC has made NAAC re-accreditation process mandatory for all higher education institutions and NIRF ratings are necessary to brighten the future of our students.

NAAC accredited us with a CGPA of 3.59 on a four-point scale. They gave us ‘A’ grade in 2016 for five years. We’re the only law university in the country included in the top 100 club by NIRF. Unlike IITs and IIMs, which are in a separate category, we had to compete with 3800 odd universities assessed by the HRD Ministry and the competition was very tough. Isn’t that an incredible achievement for a university, which hasn’t completed even a decade of existence?

It has undergone a paradigm shift, particularly after the initiation of economic liberalisation in 1991. It unleashed new challenges for law graduates as the process of liberalisation brought up many new socio-legal issues and business opportunities in the growing globalised world.

It started in 2008, when the Delhi government passed the NLUD Act on directives of the High Court of Delhi. I joined it on July 21 after hosting the convocation of my law school in Hyderabad. We started classes in September.

State-of-the-art moot court hall

State-of-the-art moot court hallYes, before taking charge of NLUD, I was the founder Vice Chancellor for NALSAR (National Academy for Legal Studies and Research) in Hyderabad, which was India’s second National Law University. I was there from 1998 to 2008. Prior to that, I had a stint (1996-97) at the National Law School of India University, Bangalore (NLSIU), India’s first law school. I had a role in the National Law School movement too.

Yes. After the first law school NLSIU started functioning in Bengaluru in 1988, no other law school came up for ten years. Five batches of the Bengaluru law school came out and its products started making their presence felt. In 1996, at a conference of law ministers in Bhubaneswar, it was decided that since the Bengaluru experiment had proved to be a success, we should open similar law schools/ universities in every state. Thus, the second law school came at Hyderabad.

A basketball match in progress at NLUD campus (left)

A basketball match in progress at NLUD campus (left)Since I was teaching at Bengaluru law school at that time (1996-97) and also associated with the national law school movement for reviving India’s legal education, their choice fell on me. Chandrababu Naidu the then Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh invited me to be the founder Director and Vice Chancellor of Andhra’s first law school named National Academy of Legal Studies and Research or NALSAR in 1998.

I was there for ten years. Interestingly, after NALSAR, new law schools came up in Bhopal, Kolkata, Jodhpur, Raipur, Gandhinagar, Lucknow and other places within a relatively short time. Meanwhile, NALSAR, Hyderabad had started making a name for itself and by 2008, we had overtaken NLSIU, Bangalore in national rankings and became the best in the country.

Right from beginning, I was conscious that I had the mandate not only to compete with NLSIU, Bengaluru, but to overtake it as soon as possible. I realised I could not beat this challenge unless I got liberal financial support to create the necessary infrastructure and get the best of faculty. I also worked hard to motivate students to acquire the technical and professional skills through moot court competitions and similar activities. Soon, results started flowing and NALSAR became known for its overall excellence.

Dance performance at NLUD’s annual fest KAIROS

Dance performance at NLUD’s annual fest KAIROSSupreme Court Justice Dalveer Bhandari visited Hyderabad around that time. Since he knew me, he also expressed the desire to visit the law school in Hyderabad. He met me at NALSAR and said, “We’re planning a law school in Delhi and if you’re interested, we'll be very happy.” To cut the story short, I came to Delhi because I belong to Haryana and my hometown is just about 100 kms from here. So, I came here in July 2008 and since then, I have been busy establishing the National Law University Delhi (NLUD).

NLUD’s Dwarka campus

NLUD’s Dwarka campus I don’t want to get into numbers, but it’s a fact that today the three best law schools in the country are Bangalore, Hyderabad, Delhi and NLUD has its own place. It is second to none in terms of quality of students, faculty, infrastructure, library, moot court competitions, debates, other intellectual activities and above all, in terms of research.

I felt, if I’ve to make NLUD known as the best law school in India and abroad, I’ve to do something different. Since the research culture is missing in most of our universities, I decided to focus on creating this culture here. With this mandate, when I recruited my faculty, I had two objectives in mind: one, to have some very eminent jurists whose experience would be a great asset to a new entity, and two, to have some young but very talented faculty who would bring the most contemporary and latest approaches to research and teaching at this University.

A class in progress

A class in progressSome are very eminent jurists like Prof (Dr) Upendra Baxi, former V C of Delhi University, Prof Sasidharan and Prof BB Pande. They joined as Distinguished Professors. We have Prof Mahendra Pal Singh, renowned Constitutional Law scholar and former V C of National University of Juridical Sciences, Kolkata. We also have Prof (Dr) A Jayagovind, former V C of NLSIU, Bengaluru and some five-six other very eminent law teachers as visiting professors. We also have some young faculty who came from abroadwith backgrounds of law schools like Oxford, Cambridge, Stanford, NYU School of Law, Yale or Harvard to carry on the culture of research. We have a strong 50-plus faculty today. We have about a dozen research centres, where we have room for 50 research scholars involved in cutting- edge research. That's why NLUD is today known as a research-centric law school.

‘If you do a good job, its vibrations travel. You need not make publicity for yourself. That’s why you find NLUD is the least-publicised institution not just in Delhi, but throughout the country. We openly say, please don't rank us. We don't believe in paid rankings. My rankings are my students’

All areas of contemporary relevance-laws governing the internet and telecom, corporate laws, transparency in governance, labour issues in informal sectors, banking and financial laws, laws relating to death-row prisoners and laws on sexual offences, to name a few.

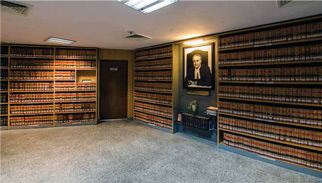

Justice TPS Chawla library

Justice TPS Chawla libraryWe do a lot of work for the government and industry, for the Law Commission, for the Women’s Commission, and various other commissions. We do research work for the parliamentary standing committees. We've been preparing the government report on human rights for the Human Rights Council. The recent human rights report was prepared by me. I was a part of the delegation to Geneva. We regularly help the government in improving the draft law for any new legislation. We do a lot of training programmes for senior government officials in different areas like income-tax or intellectual property rights or criminology. We also do similar programmes for officers of the Bureau of Police Research & Development. We also organise high-level international and national conferences, moot court competitions, workshops and seminars on newly emerging areas of law.

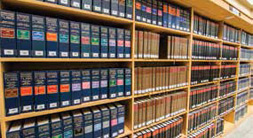

Library that offers best legal literature

Library that offers best legal literatureWe have a five year LLB (Hons) degree programme after 10+2. Then we offer a one-year LLM programme and PhD. For every course, we have an all-India entrance test. Admission to NLUD is strictly on merit. There is no quota— either for NRI-sponsored candidates or for the management. No quota even for the Chief Justice of India!

That’s statutory quota, which has to be given because we’re a public-funded institution, but otherwise no discretion to anybody.

No. I didn’t become part of CLAT, though I was instrumental in introducing it. I decided to have a separate test called the All India Law Entrance Test (AILET) conducted by NLUD.

V C Prof Ranbir Singh with members of a foreign delegation at NLUD

V C Prof Ranbir Singh with members of a foreign delegation at NLUDFor 2000 seats of CLAT, they get some 50,000 applications for admission to 18 National Law Schools (NLS), 43 other educational institutions and two public sector institutes. Incidentally, CLAT is conducted by 18 participating law schools in rotation and its uniformity of standard varies. However, for 80 seats of my fully-residential, five-year programme, I get about 18,000 applications; about 1100 for LLM and about 175 applications for PhD. The undergraduate

programme is based on a credits system with additional seminar courses for further learning, pursued as per the interests of the students. It consists of about 50 subjects over ten semesters, five in each semester. Students are expected to submit 50 research projects before graduation.

I have a highly motivated faculty and the faculty- student ratio is 1:8. I give a lot of freedom to my faculty to be creative and innovative. If they want, they can devise their own curriculum and change it every semester. I give them the latest audio-visual tools to explore different ideas and make the classroom experience stimulating.

With foreign delegates at a conference at NLUD

With foreign delegates at a conference at NLUDThey love it because our students are intelligent. The faculty knows that if they don’t go fully-prepared, they’ll face a tough time in class.

We constitute a students' bar council within a month of admission and then students themselves organise all activities. My job is to give them money. We also have college mentors to help them. It’s a student-centric law school where they’re involved in almost every activity.

They stand out. They’re the finest lawyers today. When they go to the High Court and Supreme Court and argue, judges ask them, which place you are from? When they tell them where they’re from, even judges acknowledge the difference.

It’s the research-oriented, disciplined and methodical approach and analytical and critical thinking that we teach them. It helps them stand out.

The girl, who recently topped the Delhi Judicial Services was from NLUD. The girl, who topped Punjab Judiciary Services was also from NLUD. The girl, who topped in Haryana too was from NLUD and the youngest girl in 2014- 15 to have been selected in the IAS, Aashika Jain, is also from NLUD. Two years back, the Rhodes Scholar was selected from NLUD. There are only two scholarships awarded by Rhodes in the field of law and Rishika Sahgal, a BA, LLB (Hons) student, became the first from NLUD to receive this rare honour. Our students have also won various national and international moot court competitions.

Delegation of Uganda

Delegation of Uganda No. It wasn’t like that. Students never wanted to stay in the hostel for fun. They wanted the hostel to prepare for the civil services. In those days, their journey for IAS would usually start from Allahabad University. Gradually, it switched from Allahabad to Delhi University (DU). People would join law and stay in DU’s Gwyer / Jubilee Hall, and compete for the civil services. From DU, it shifted to JNU and from JNU it went to the IITs. Now from the IITs, it’s swiftly shifting over to law schools and in another ten years, we'll take over the IITs. The maximum number of students in the civil services will come from law schools like NLUD. That's how it’ll continue because law as an optional paper has a comparatively higher rate of success in civil services than other optional papers, giving an edge to our students.

Actually there are three levels at which legal education is imparted. Standards also vary substantially. At the base-level, we have about 1600 law colleges, mostly in the private sector, offering five-year courses after class 12. Then there are about 250 universities, offering three-year law courses after graduation. Some also offer five-year integrated courses. Then there are about a dozen distance-learning law schools like IGNOU, Annamalai, SNDT Mumbai, etc.

V C with students who won trophies for NLUD

V C with students who won trophies for NLUDActually, until the 1980s or maybe early 1990s, the law faculty of the universities of Lucknow, Allahabad, Benaras, Kurukshetra and others were doing an excellent job. These were nurseries for producing good quality lawyers and teachers. But, unfortunately, because of faulty government policies, standards in these law faculties also fell miserably.

The Automatic Promotion Schemes and Rotational Headship Policies. Faculty got ruined, the quality of teaching suffered in the process, and the decline was so fast that now we don’t know how to improve.

Yes—it was. Legal circles, especially in academia, were very much agitated. Heated discussions took place. Everybody felt that something must be done fast to improve the standards of legal education.

‘By conducting an entrance test soon after 10+2, if you can select the best of the students for medical and engineering colleges, why can’t you do the same for law schools? If students join a high-quality, integrated 5-year BA, LLB course, they’ll naturally be more motivated, focussed and committed to the profession’

People felt our colonial masters were not interested in good legal education for Indians but now things must change. We badly needed reforms. But even seven decades after independence, our policy makers had not done anything to revamp it. The result was, we had a large number of private law colleges in the country, but very poor quality control.

First, it is the Bar Council of India (BCI). But it had very little control over standards of legal education. Most students would join law because they had nothing better to do. Second, the bulk of LLB/LLM education was part-time. So, while doing law, you could also do an MA in history, or whatever. Third, most law colleges had poor faculty, mostly part-timers, poor infrastructure, no library or research resources. Fourth, mass admissions in law courses also led to a sharp decline in standards of teaching and evaluation. Legal education was in a complete mess. Nobody took it seriously, yet nothing was being done to reform it.

Though the Law Commission voiced its concern in 1958 itself, it was only in the early eighties that a legal education committee headed by the former Vice President of India, Justice M Hidayatullah, was constituted. Prof Upendra Baxi and Prof GL Sharma were its members from the academic side. It also had eminent lawyers like Ram Jethmalani, Ranjeet Mohanty, Rajinder Singh and a few others. After several meetings, they came up with the idea that to have something on the pattern of law schools in America. They recommended a five-year double- degree, integrated law course. Initially the BCI decided to scrap all the existing three-year law courses, but it faced stiff opposition from academia across the country.

Those who favoured three-year courses felt it wasn’t a solution to close them down. Others wanted to give the proposed five-year course a try. Some also recommended a four-year integrated course and so it became controversial. Finally, in 1985, BCI resolved to allow both the five and three -year law courses to function simultaneously because it observed that some people decide early, while some take time to realise that they have to do law.

It did, but in 1987, after years of deliberation, all confusion evaporated when it was decided to establish the first National Law School of India University (NLSIU) in Bengaluru. It started functioning in 1988 and since then it has been a trend-setter in legal education. Though Prof Baxi was supposed to translate its vision into reality, since he had some other commitments, this responsibility was finally given to Prof Madhav Menon of DU who was well-acquainted with this goal. He accepted the challenge and became the founder-director of NLSIU Bangalore. Today he is considered by many as the father of modern legal education in India. The rest, of course, is history.

The logic was, by conducting an entrance test soon after 10+2, if you can select the best of the students for medical and engineering colleges, why can’t you do the same for law schools? If students could join a high-quality, integrated 5-year BA, LLB course, they’ll naturally be more motivated, focussed and committed to the profession. So, efforts were made to prepare an integrated course curriculum.

That was done because it was felt that legal education must have a multi-disciplinary approach so that it is socially relevant for proper dispensation of justice. That’s why Social Sciences (History, Political Science, Sociology and Economics) were added alongside standard legal subjects such as torts, contracts and constitutional law.

‘Your performance in terms of teaching, research, discipline, perception you create, the kind of students you produce—these should be the parameters. Unless and until you compete for that, the universities will be in a bad shape’

Almost 50%, but lately girls are in more numbers. In fact, most of our best performance awards have been won by girls.

The beautifully well-kept NLUD campus which provides uniquely furnished spaces for intellectual discussions NLUD

The beautifully well-kept NLUD campus which provides uniquely furnished spaces for intellectual discussions NLUDOur system is very different. I cannot speak for others but at NLUD, we have a very strong system of internship, which starts right from the first year. A first-year student has to go for a six-week compulsory internship at the library so that he can understand what is legal literature, what is legal database, how to consult a library, what are the documents you need for research and so on.

In the second year, you do an NGO placement to understand the interface of law and society because when you work for an NGO, you come to know what problems women, children, the aged, street children and the destitute face, and learn how law can help them. Students get socially sensitised. Similarly, when they come to the 3rd year, they go to the Trial Court because it’s very important to understand trial court procedures. When they come to the 4th and 5th years, they start going to corporate law firms, senior lawyers, judges and multinationals. They even go abroad for internship. So, it's a very continuous process of internship at NLUD. By the time they pass out, they have been through all these systems which are very important interfaces for a lawyer.

The idea is three fold, to produce lawyers who are technically sound, who know and understand the interface between IT and law and who are professionally competent through moots and debates and all these activities. They get proficiencies in languages; they speak the legal language and do all the things that are socially relevant. They attend legal aid clinics and lok-adalats to become socially relevant people. They enter a purposive order so that they become not only good advocates but good human beings too. We try our best.

We must give teachers the importance they deserve. Unfortunately, today they don’t matter. Only politics and politicians matter. Nobody bothers what teachers have to say. There was a time when our universities had lots of autonomy. Now there are instances where people are being regulated at the state-level universities for no reason. Universities should be very autonomous bodies. They must, of course, be accountable for what they do and the indicator should be nothing but performance. All grants should be performance-based. Your performance in terms of teaching, research, discipline, perception you create, the kind of students you produce— these should be the parameters. Unless and until you compete for that, the universities will be in a bad shape.

Away from the din of Delhi, NLUD offers fully-green, picturesque and world-class campus

Away from the din of Delhi, NLUD offers fully-green, picturesque and world-class campusWe have several collaborations with the most prestigious law schools abroad including Harvard, Oxford, George Washington (USA), Wallamette (USA), Lewis & Clark (USA), Osgoode (Toronto), McGill (Canada), VU (Amsterdam), King’s College (London), Maastrichit (The Netherlands), Melbourne (Australia) and Johannesburg (South Africa), to name a few.

These MoUs pave the way for smooth student/ faculty exchange programmes.

That's because we have the best of students but we lack the best of institutions. So our brightest kids go abroad and many of them never come back because the scene abroad is just the opposite. They have the best of institutions but they don't have students. So, you’ll find Indian students in top universities of USA, Canada, UK, Australia, Singapore and Hong Kong. How much we contribute to their wealth is anybody's guess but we’re not bothered. Nobody in India has the time to look into these things.

Oh yes. We’re already in the ICU. Except for a few private schools in the cities, primary education is dead. You don't have good high-school education. You don't have quality college education. Though it’s more than three years now, the central government hasn’t implemented the grades of teachers, till date. They are yet to decide who’ll bear the burden.

We’re nowhere. Universities in countries like Singapore which came up recently have far higher world rankings. The Nanyang Technological University which came up only 15-years back is the 15th world-ranker today. Similarly, National University of Singapore, or INSEAD— each enjoys top ranking in the world. It’s because they believe in excellence. If they find good people, they go out of the way to retain them. That's how excellence is promoted.

The fee I charge for admission at NLUD is some Rs. 1.75 lakh per annum. This includes all expenses including hostel, except the mess. This is peanuts if you compare it to the fee charged by private players. If somebody finds it difficult to pay, we provide liberal funding too. That’s not much because once they pass out, their minimum salary at a corporate law firm can be Rs. 1 lakh per month.

One very learned judge said, the quality of judges would be determined by the bar and the quality of the bar would be determined by the law school. But, till date, not even a single teacher has been taken into the SC as a judge, though there is a provision under Article 126 that a jurist can be taken to the SC. No law teacher is taken in any tribunal or commission. They’re not taken even on the National Human Rights Commission or Competition Commission of India. Those who teach these subjects day-in and day-out are not even considered for these institutions. They’re persona non grata. This is how our country is run by experts.

Most of them would be bureaucrats or judges. So why would good people come to teaching? But the best of countries in the world are those which respect their teachers, their women and take very good care of their children. We do none of that. How can we call ourselves great if we keep wasting our human resources like this?

Our justice system is bogged down with judicial delays. Why can’t we implement the recommendations made by several committees and law commissions? Why should we have multiple appeals? Why do we allow adjournments that delay the process? Why do we allow stays? Why is the government itself the biggest litigant in India? Why can’t we have more fast track courts? Why can’t we modernise our courts? Why can’t we keep our courts open 365 days a year and increase the strength of our judges ten-fold? Why do we allow lawyers to stall the cases on grounds of someone being absent or medical emergencies or paperwork problems and so on? Why can’t we do away with archaic laws of the British era which make no sense in today’s world? Even the layman knows, if we have to clear this mind-boggling backlog of over three crore cases in India, we will have to take some drastic measures urgently but then the question arises: Who’ll do it and are we really serious about it?

I like teaching. I even teach here. I have been a V-C for 20 years, but I teach every year. Earlier I used to teach senior classes but now I teach first year students. I love to teach them. The teacher in me is always alive. That is the most enjoyable thing I know.

My vision is very simple. Ten years from now, I want NLUD to be ranked among the best in the world. I want NLUD products to be highly technical, socially relevant and extremely competent. I want them to be the leaders, not followers, of New India.

Do your best. Do your job sincerely. That's it!

By Pradeep Mathur