Dr Karuna Ganesh, physician-scientist at the world renowned Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, is involved in unravelling clues to cancer cell behaviour at their most dreaded phase, metastasis, to curtail its spread and impact

Dreaded as the disease cancer is, it enters the most devastating stage when it turns metastatic -when it spreads to other parts of the body than where it first began. Metastasis leads to over 90% of cancer death.

Dr Karuna Ganesh is a physician-scientist at the world famous cancer research centre, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, focused on investigating and treating cancer metastasis -- by understanding what drives these cancer cells to grow and flourish – and thereby kill.

Following her early education in India, Dr Ganesh completed the International Baccalaureate at the United World College in NM, USA, and studied as a Gates Scholar at Cambridge University, UK, gaining a medical degree and a PhD in molecular biology.

She then trained in internal medicine at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School. She joined the medical oncology fellowship program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in 2013, and since July 2014, has been working on metastasis. In an intense interview with Corporate Citizen, Dr Ganesh talks of her single minded pursuit of medical research and the need for intense medical and research interface to fight the scourge and bring it to more manageable levels.

All of this started when I was 12 years old. I loved reading books, I still do. I started reading novels by Robin Cook, an ophthalmologist at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Institute. His books were all medical thrillers and the detectives who solved the mystery used medical mastery. There I came across the physician scientist for the first time -- a scientist and also a doctor. That captivated me and I decided what I wanted to do.

At that age when you tell others about such dreams, nobody takes you seriously. Those were also the days of early Internet and I was lucky that both my parents were in the IT industry, so we had a computer at home and also the Internet. I started researching how to become a physician- scientist, I realised there was nothing like that in India and everything was primarily in the US. So I applied and got into an international school in the US and discovered that Cambridge University in England had a similar programme, where, like in India, your medical program begins right after school. So the night before the applications were closing, I applied to Cambridge and got in.

Ten years later, I completed my education in medicine and science at Cambridge and moved to the US to pursue my career in this field.

My parents were of course a huge influence, specifically my mother. She has a very strong personality and was the dominant influence in my life while I was growing up. She sets high goals and does everything to achieve them and consciously or subconsciously that became ingrained in me. Also, I realised that it is always easier to achieve your goal if you know what it is. In terms of career goals, it is important to think rationally and make strategic decisions --to figure out your strengths, your weaknesses, what makes sense, and then just go for it!

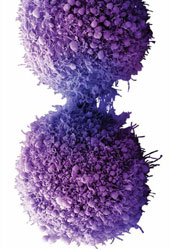

Cancer is a group of diseases defined by uncontrolled growth. All cancer starts off in one part of the body - the breast, or the lung or colon (intestine) and so on. But usually, that tumour kills a person not because it is growing in one place but because it learns how to spread from the organ where it started to other parts of the body. For example in breast cancer, it typically spreads to the lung and brain and that’s what really kills people. We don’t fully understand how that happens at the molecular level and that’s what my research is focussed on. Cancer cells retain the ability to grow uncontrollably but they also adapt to live in a different environment. You know breast cells are designed to grow in the breasts; they don’t know how to survive in the brain. But cancer cells learn to survive in the brain and other parts of the body like a parasite which ultimately devastates the functioning of the organ, the body and kills people. I am trying to understand the molecular drivers that enable cancer cells to flourish in alien places, in very hostile environments. If we learn enough about their vulnerabilities and can exploit them, we can then make new drugs to destroy metastasis, and eventually hopefully cure advanced cancer.

Because of the feeling that cancer is something that will kill you. With diabetes or heart problems, you can manage it with drugs and control it and keep going for a long time. But with cancer, it feels like death is staring you in your face. But that’s not always true; there are many types of cancer that we now know to treat and cure. The other fear is the treatment of cancer. Historically, we have had very aggressive treatments like chemotherapy that can have severe side effects, and people have very horrible associations with it, having seen their friends and near and dear ones go through it. We need to better cancer treatments that are less toxic. We are getting there, slowly, and with recent developments in targeted therapy and immunotherapy we are already making rapid progress.

‘All cancer starts off in one part of the body - the breast, or the lung or colon (intestine), etc. But usually that tumour kills a person not because it is growing in one place but because it learns how to spread from the organ where it started to other parts of the body’

I am really glad that you asked me this question. Especially in an Asian family, culturally we are inclined to protect our relatives from the truth. But the most important thing to do is to stay honest. Even if you don’t tell your grandmother that she’s dying of cancer, she knows. Trust me. And it creates a barrier of fear if people cannot talk honestly. Truth is the first thing required and then clarity about the process. Sometimes, time is short, and it needs to be communicated in a sympathetic way to the patient. It is important for people to plan their lives, their families, their relationships, to have honesty and clarity. It also lessens fear if you know what you can expect.

That is a tough one to answer. You have to tailor it to every individual and it is hard. I know a lot of cancer patients who get very alienated because their friends and family don’t know how to respond. So they just stay away or sometimes people come and overtly try to provide support in their own way. You just need to be honest because honestly helps, and dialogue with the person helps too. You should ask the person what he or she wants. Sometimes, they need space; sometimes they want somebody to be with them. As doctors we can definitely reassure people they are not going to die in pain -- this is the big thing that people are really afraid of - dying in pain and agony. This is something that we fully have in our control now.

There has been a huge revolution. Historically, our treatment for cancer was radiation and chemotherapy. They are very blunt instruments. They just kill anything that is growing fast. That makes for a lot of toxicity because our hair cells are growing; our blood cells are growing. That’s why we have such horrible side-effects. In the last decade, we have understood a lot about the molecular basis of cancer and now we have what we call targeted therapy. They specifically target the cancer cells, and do minimal damage to normal cells, resulting in fewer side-effects.. In the last decade, the real revolution has been in immunotherapy which is getting your body’s own immune system to fight against cancer cells in the same way as it defends against infections. It makes your immune system see cancer as the foreign object and destroy it. Sometimes, the responses are really miraculous. For instance, skin cancer – metastatic melanoma – was historically a near universally fatal disease. Patients with this disease who earlier were not able to survive for more than three months now live for decades with immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy is about teaching your body’s immune system to fight cancer, through medicines. Our hope is that as we grow in this area, Immunotherapy will be a lot less toxic, and even better at destroying cancer. The beauty of immunotherapy is that unlike any other kind of treatment of cancer, you can get long term durable responses for cancer. Right now, when you have an advanced stage cancer, it still is largely a death sentence. However, our goal is to convert cancer from that kind of death-sentence-disease into a more manageable disease, like say high-blood pressure or diabetes -- where you still have the disease all your life, but it can be controlled through medicines. Our goal is to convert cancer into a manageable chronic disease rather than a death sentence.

‘In India, there are fantastic hospitals and great research institutes but not really much crosstalk between the two of them. Crosstalk is crucial: we need science to develop medicines but we also need the clinical understanding of what the patients are facing, what the side effects of these drugs are’

Yes definitely, it is available in India. Right now, ,we know it works only for some types of cancer. But there is tremendous interest worldwide in trying to improve Immunotherapy and make it work in a larger spectrum of cancer types. And not just Immunotherapy but chemotherapy and targeted therapy as well - someday we may see a combination of all three to treat cancer, and convert cancer into a chronic disease.

I would love to be able to say yes, for prevention definitely, but for treatment right now there is not enough evidence for any reversal or type of food or lifestyle that can truly treat cancer. For prevention, of course we certainly know that stopping smoking can prevent lung cancer. There is some evidence for not eating red meat to help prevent colon cancer. But to associate a lifestyle with prevention of a certain kind of disease - it is often difficult to establish causality.

It is a fantastic place to work, we have people coming from all over the world. There is very good integration of medicine and science which is exactly what I am doing. Both sides learn from each other. In India, there are fantastic hospitals and great research institutes but not really much cross-talk between the two of them. This crosstalk is crucial: we need science to develop new medicines but we also need the clinical understanding of what patients are facing, what the side-effects of these drugs are, and so on.

They are, but primarily second generation Indian Americans. In the field that I am in, which is a super-specialised area of research and science, it is hard to get from India, as there’s no training available in India. Usually when Indian doctors go the US, they tend to be clinical doctors practicing medicine, and sometimes conducting clinical research. Some Indian doctors do get advanced research training in the west and then go on to conduct scientific research.

The UK and the US have very different healthcare systems. The UK has the National Health Service, so everybody pays for it through tax, but when you need the service, it is completely free. So no matter how rich or poor you are, you go to the same hospital and receive the exact same service and treatment and nobody asks you for money, which is really fantastic. In the US, the system is similar to India, where some people have insurance; some don’t. So depending on which hospital you’re working in, you may see different kinds of patients. At the lower end of the spectrum there are many people who have not had treatment for many years and when they come to the doctor, they may have a very advanced stage of disease. At the upper end, it is usually good as you may get the latest drugs, absolute cutting-edge technology which may not be available here in India. But again, sometimes it is bad as people may get over-treated unnecessarily. But when you come to an academic teaching hospital like ours, where physicians are paid a fixed salary and are not driven by fee-for-service payments, you can get the best care based on the best scientific evidence. I’ve heard from my friends in India about incentives to doctors for overcharging patients, or pushing them to unnecessary procedures to make money which is an unfortunate part of our system.

For some kinds of cancer we know there are established protocols. Like for breast cancer, or cervical cancer, we know that if you use a certain technique there’s a good chance of detecting them. Camps are a great way for patients who don’t have access otherwise to get such preventive screening. The problem is that these screening procedures work if you do them regularly. If not, that may result in under-detection.

Yes, very much, but that way, I learnt to be independent at an early stage. I left home when I was 15 years old, and then remained independent throughout. Also, I am in a field my parents know nothing about. I was not a pampered, protected child and they always set very high expectations for me. If I came home with 99% marks, the question would be where did that 1% go? Perhaps that was good for me, as it motivated me to try harder.

He is a management consultant now, but trained as a particle physicist. We met at Cambridge, while we were both doing our PhDs. On our first date, he said he was leaving the country in one week and go work in Switzerland because that’s where his experiment was. He sort of disappeared for a year. After he finished his PhD, he moved to Harvard. While he was in Switzerland, we had this multi-country relationship for a very long time. And it is only in the last two years that we have been in the same city.

‘As doctors we can definitely reassure people they are not going to die in pain -- this is the big thing that people are really afraid of - dying in pain and agony. This is something that we fully have in our control now. I can promise that they will not die in pain’

It is important in any relationship to keep an open mind and learn from each other. It helps that he loves Indian food! I had been living in the UK for a long time before I met him, which familiarised me with his culture. I went to an international school in the US, which broadened my mind and allowed me to be grounded to my Indian culture, yet left me open to new experiences, new ideas and new people. That probably helped us. Of course we grow together; every day is a conversation where we learn something new about each other. You try and respect each other’s perspectives as much as possible. That goes for any relationship, whether you’re of the same caste, religion or country.

It felt like I was hit by a truck! Everything was so overwhelming; you were plunged into a sea where everybody was totally different from you and from each other. I had to learn from everyone around. It really forced me to think about what my identity was. That helped me identify the parts of my background, my culture, that were very important to me and those less important. That is important when you leave your home and country and go to a different land. Adaptation is crucial. And while you adapt, you also get to reflect what is important to you from your previous identity. That helped me a lot, as I moved multiple times after that - from India to the US, then UK and then back to the US.

It is important for me to make a difference, wherever I can, whenever I can. It’s important for me to have integrity, to be open to new ideas, people and different influences, wherever they come from. And to really understand that every experience you have is something to learn from.

by Vinita Deshmukh