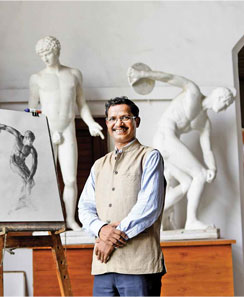

It is so much more than an institute. It is the journey of a nation’s artistic sensibilities, its evolution down the ages. Sir J. J. School of Artstands testimony to this voyage, and the nurturing of legacies that carry forth to posterity.It’s Dean, Vishwanath Sabale, traces the path and aspirations of this illustrious century-and-a-half-old institution

It is so much more than an institute. It is the journey of a nation’s artistic sensibilities—and its evolution down the ages. Undoubtedly, when you take admission to Sir J. J. School of Art, you have a lot to live up to. But Vishwanath Sabale, the present Dean, will have you know that art starts way before your mind and hand conceive and shape the concept. “It lies in the history of the movements and aesthetic values that allowed you—the artist—to reach the point that you have today,” he says.

While the mother institute aka the J. J. School of Art was set up by the philanthropist Sir Jamshetji Jeejeebhoy in 1857, the Institute broke up into the J.J School of Art, the J.J School of Applied Art and the J.J College of Architecture in the late 1950s.

While the first two come under the aegis of the Directorate of Art, the architecture college comes under the University of Mumbai.

Originally started in the 1850s to train local craftsmen in weaving, pottery, painting and sculpture, the Institute split into the “pure” art school (now headed by Sabale) and the job-oriented courses (offered by Applied Art).

So even as he is conscious of the responsibilities the ‘JJ’ name brings with it, he has wellthought- out plans to rev up the curricula—from the introduction of the master’s programme for various courses to courses on restoring and preserving old works of art to digitizing the library and building more space for many more students to thrive.

This restoration project is imperative not just to preserve art for posterity, but also to understand the growth of the artists as individuals. The project is also aimed to educate present students, on the process and technique undertaken by these artists, over the years and how their styles have changed the image of Indian art forever on the international platform

As of today, we give Bachelor’s of Fine Arts degrees in Drawing and Painting, Sculpture and Modelling, Ceramics, Metal Work, Textile Designing and Interiors. While we already have a Masters’ programme in Drawing and Painting, we are soon beginning a Master’s degree programme in the other categories as well. We also have a Diploma programme in Teachers’ Training and Sculpture and Modelling.

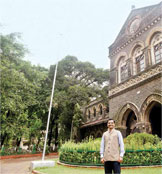

Space is a challenge—given that the heritage structure of the building was set up a good 138 years ago (although the Institute is over 158 years old) and our capacity is 30 students for Painting, five each for Ceramics, Metal Work and Sculpture, 15 each for Interiors and Textiles.

In the Diploma courses, 30 students are enrolled in Teachers’ Training and 10 in Sculpture.

In post-graduation, 20 students are enrolled in the Painting course while the rest of the courses have five students each.

Abroad, they study the evolution of various socio-political-economic movements and understand each master in that context. This is very necessary for art education to be holistic and I hope we can do something about it soon

Many, many things. From the consciousness of coming to a school that has the who’s who of the arts world (see box on page 23) on its rolls to actually getting to practise one’s craft in an atmosphere created especially for it, we go the whole, wide distance to encourage, nurture and nourish the artist. An artist is never created in a 10×10 classroom, but through application and the support of the correct atmosphere.

Keeping this in mind, the building has studios of sculpture, ceramics, metalwork and paintings designed to get plenty of natural light. We have windows that go from the floor to the roof—almost 20 feet high—thereby allowing the sun in. This is vital, for example, for life Portraiture—the very lifeline of painting and sculpture.

Apart from this, the college campus—which is simply picturesque and beautiful—is encouraging for the finest artistic sensibilities. Bright splashes of colour in the canteen—not to forget the natty little slates hanging from the canopy of lush green trees around a beautiful and stately campus definitely adds to the welcoming feel. Also, the sheer pride of studying in an institution as historic as this one strategically located in the heart of Mumbai city is immense.

Importantly, it is close to the premier art district, Kala Ghoda, which is surrounded by renowned art galleries such as the Jehangir Art Gallery and National Gallery of Modern Art, to name a few. This keeps the students abreast of the latest developments in the world of art.

Equally vital—the school is located in the historic Fort area of Mumbai, which has a series of British Gothic style buildings which are unique and beautiful in their own way.

I would say it’s the perfect inner and outer world for any artist. Unlike most other institutes today where classrooms meant for something else have been converted into studios.

That’s not all. We regularly bring in the greats from various fields—not just the arts—to speak to the students. So be it the spiritual guru J Krishnamurti or cultural greats like Bhimsen Joshi, we have ensured that students to listen to great minds.

Apart from this, the Institute is also engaged in various socially relevant activities that sensitise the students to the world around them.

We have round-the-year art competitions for schoolgoing kids, apart from regular workshops for physically handicapped children as well as cancer-afflicted children from the Tata Cancer Hospital.

Similarly, the Elephanta Festival conducted by the Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation (MTDC) was initially dedicated only to music but participation from JJ included exhibits of artistic work as well.

Recently, the students did as many as 30 paintings for the Nehru Science Centre on ‘Water, The Theme for life’. Water scarcity being a major issue confronting Maharashtra today, we held an art competition at Mantralaya in March on the theme of water preservation for the public. Thus, engaging with the public as well as the pressing issues of the day is a wonderful way for artists to interact with and understand their surroundings—apart from giving back to it.

One of the major tasks before us is to restore, preserve and properly display the paintings of our famous alumni—this in order to track their progress, their growth from mere students to masters. This is a Herculean task—given the constraints of time. Most of their works were discoloured due to ageing, dust and dirt. While some canvases, especially the works in oil, had signs of wear and tear on them, others were in deteriorated conditions due to the accumulation of fungus, loss and flaking of the paint layer. The varnish layers on them were yellowed and had developed cracks in them. Some works even had major and minor cracks. A few paintings including the ones on paper had suffered fungal and insect attacks due to high humidity.

One has to take care not to disturb the original antique feel and finish of the era—even as you clean it up, treat it and lend it appropriate support. The process is both scientific and tedious.

We have around 2,500 works with us between the years of 1870 to 1970s and we are restoring them step by step. So there are paintings by VS Gaitonde done during his student days, by SH Raza at the start of his career and even that of Atul Dodiya in this collection. This restoration project is imperative not just to preserve art for posterity but also to understand the growth of the artists as individuals. The project is also aimed to educate present students on the process and technique undertaken by these artists over the years and how their styles have changed the image of Indian art forever on the international platform.

Since 2011, we have an expert team of six from the National Research Laboratory for Conservation of Cultural Property in Lucknow working on this restoration project. To date, around 750 paintings have been successfully restored.

Well, academic autonomy would be welcomed anytime. Apart from holding collaborative projects with universities in India and abroad, we can enrich the experiences we offer.

However, financial autonomy is a double-edged sword. If one were to get complete financial autonomy, we would have to increase the fees substantially, which means the college would be out of the reach of rural students. One would definitely not want that to happen, for some of our finest talents are bred in the villages, and deserve a chance.

Not at all! Unlike the commercial courses that are directly linked to the daily pressures of the job market and have to compulsorily keep in sync with the technical trends of the day, the changes here are not as immediate.

It is neither required nor desirable for different art schools (in Mumbai or across the country) to have a common syllabus in the interest of artistic progress. As the saying goes, let a thousand flowers bloom!

There’s a lot to be desired, for sure! Human learning begins with lines and figures, and then moves on to the alphabet. There are so many concepts that are best depicted through illustration and pictures, yet our curriculum in schools do not give art the place and space it deserves. There was a time when a drawing teacher was an integral part of every good school, but today, the picture is vastly different. There are plenty of institutions that seem to think they can do perfectly well without art—but that’s wrong.

Art brings out the best in a human being; it is both an outlet for one’s expression as well as a canvas on which to project your aspirations. To not teach it in school—and then expect a youngster, however talented, to make up for lost time in college, is unfair. Art is, therefore, not a disposable entity but an integral and central figure in any quality education.

No, it is not. It’s all about balancing your passion for your specialisation with commercial work. If you are good and disciplined towards your art, you will be able to take on commercial assignments that allow you the freedom to do work that fulfills your finest creative potential. However, all of this takes patience. Art is like a tree; you have to duly water the seeds to solidify the roots and grow the shoots. Patience and practice are the key to everything.

From the consciousness of coming to a school that has the who’s who of the arts world on its rolls to actually getting to practise one’s craft in an atmosphere created especially for it, we go the whole, wide distance to encourage, nurture and nourish the artist. An artist is never created in a 10×10 classroom, but through application and the support of the correct atmosphere

I did my schooling and college in Pune—passing out from the Abhinav Kala College with a Diploma in Drawing and Painting in 1993. Post this, I did my Post Diploma in Art Education at JJ. Through MPSC, I joined JJ as a lecturer and then was promoted to the position of professor in 2005. I upgraded my education with a master’s in Painting from the University of Aurangabad, following which I was appointed Dean in 2011.

From the very outset, I wanted to be a teacher, and took care to pick up every skill and nuance to be a good and dedicated one.

I enjoy painting and practise it at every chance I get. To be a good teacher, one has to be in regular touch with one’s art—and I make use of little pockets of time, on weekends, holidays, and even otherwise. Nature is a recurring theme in my work—it is splendid and endlessly multifaceted— and you never run out of things to paint.

A recent exhibit of mine titled ‘Summer Show’ showcased all the bounties of summer— from the gulmohar tree in full bloom, to the other fauna and flora. Nature requires you to observe her closely to do her complete justice, and that is a challenge for every artist.

To have a master’s and PhD programme for each course; have courses on art history to understand how and why we are standing at the point that we are today. In this country, we don’t study the history of art in depth. Abroad, they study the evolution of various socio-political- economic movements and understand each master in that context.

It is very necessary for art education to be holistic and I hope we can do something about it soon.

We also need courses on art restoration and preservation—the latest scientific techniques and processes, in order to preserve our old artistic treasures.

Also, apart from the Kipling House (see box on page 22) that is being renovated as a museum, we need another museum on campus for the sheer number of works we have. It is a state treasure and needs to be accorded due dignity.

Digitisation of our library, and bringing in more books on music and literature in order to understand art better is a major challenge too.

By Kalyani Sardesai