As of 2016, the food and grocery market in India is worth Rs.3,52,800 crore. Despit that, not many online players have managed to tap into this enormously lucrative market—that is, with the exception of Bigbasket. With more than 14,000 products and over 1,000 brands listed on their catalogue Bigbasket is known to be India’s largest online food and grocery store, and is a trailblazer which has consistently gone against conventional methods of doing things. To evaluate the success of Bigbasket and its plans for the future straight from the horse’s mouth, Corporate Citizen had a candid conversation with its revolutionary CEO Hari Menon. Read on.

According to a report published by Nielson (earlier in the year) based on a survey conducted in 60 countries, a quarter of people who took the survey were ordering groceries online and 55 percent intended to do so in future. Another study states that the food and grocery retail in India is in excess of Rs.3,52,800 crore of the total Rs.58,80,000 crore retail market in India. While the overall growth of retail is fuelled by the 30 crore middle-class population, the e-tailing part is growing owing to the massive adaptation of ecommerce among the younger generation.

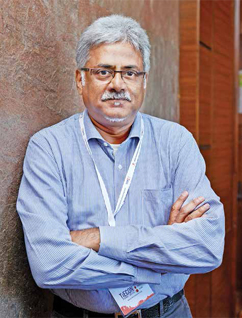

India’s booming online sector holds a great potential, a fact which did not escape the imagination of Hari Menon. This is probably due to the fact that Bigbasket is not Hari’s first venture. Over a period of time, Hari had also been an integral part of quite a few companies. Prior to starting Bigbasket, Hari co-founded Fabmart, one of the pioneers in the e-commerce in India and its physical extension – Fabmall. And before venturing out with Bigbasket and Fabmart, Hari was the CEO of India Skills—the vocational education joint venture between Manipal Group and City & Guilds (UK), as well.

A lesser-known fact is that, Hari had also served as the Country Head at Planet Asia— which was one of the first Internet services businesses in India, and had begun his career with Wipro as a Business Head in the info-tech business.

In 2011, along with Fabmall founders VS Sudhakar, Hari Menon, Vipul Parekh, VS Ramesh and Abhinay Choudhari, Hari cofounded Bigbasket, with an aim to make the hectic life of the metro-resident easier. Bigbasket promised timely delivery of a wide range of options in every food category including Fruits and Vegetables, Spices and Seasonings,Packaged Products, Beverages, Personal Care products, Meats, and many more.

Bigbasket wasn’t the only one that sensed the potential in the online food space, though. The entry and funding of hyper-local delivery startups along with the growing interest of some big names generated a lot of buzz in the e-groceries segment. Gurgaon-based PepperTap raised $10M last year to expand to 10 cities by the year end. Bigbasket’s closest competitor Grofers had raised $35M at a $115M post-money valuation. Paytm and Ola have announced their entries in the grocery market with Zip and Ola Store, respectively while Amazon had launched Amazon Kirana. Among the larger corporates, Reliance Direct Fresh and Godrej’s Nature Basket have started selling groceries online. Other players in this segment include Gurgaon-based Satvakart, Mumbai-based Localbanya, Bengaluru-based ZopNow and Jiffstore and Chandigarh-based Jugnoo.

However, Bigbasket stands apart from the competition in one crucial aspect. Among all the players in the groceries segment, Bigbasket seems to be the only one not adhering to convention. It has opted for the inventory lead model (which involves directly sourcing the produce from the farmers and holding inventory as opposed to directly sourcing it from suppliers on demand) while other startups are opting for zero-inventory model.

The inventory model helps Bigbasket to extract significantly higher margins as it buys directly from brands and manufacturers, whereas other hyper-local startups operate on wafer-thin margins. These startups essentially source products from retailers and get paid two- 10 percent of the order value as commission. This strategy seems to be working, as Bigbasket raised $150 million in fresh funds in March 2016, giving it additional firepower against smaller rivals Grofers and PepperTap, both of which have shrunk operations after an expansion spree led to losses without yielding sufficient sales. Bigbasket also has a significant private-label portfolio, which accounts for about one-third of its revenue. The company sells fruits, vegetables, meat and bread under the brand name Fresho and staples under the Popular and Royal brands.

The next round of funding might just take Bigbasket’s valuation to anywhere close to $1 billion. This might be enough to give a regular person airs, but not to Hari Menon, who remains grounded. This is probably due to the fact that despite his lofty achievements, Hari was born into a middle-class family that lived in Bandra, Mumbai, and was always taught to lead a life that gave him a settled life, a stable job, etc. When he graduated from BITS, Pilani, it was the urge to experiment that pushed him to try out something new. When we caught up with him for a chat, the grocery czar was soft-spoken, modest and went straight to the point.

“When it comes to groceries, it is not a price game. We are not discount players. I think e-commerce companies should focus on building a long-term sustainable model and stop depending on discounts to attract consumers. Our value proposition is convenience. Customers can order items from the comfort of their homes and have it delivered to them”

When it comes to groceries, it is not a price game. We are not discount players, and nor are the grocery shops. I think e-commerce companies should focus on building a long term sustainable model and stop depending on discounts for attracting consumers. Though buying customers is important in the beginning, continuing that as a business model is not sustainable. Also, discounting doesn’t work in food, because customers become skeptical about the quality of the product. It is a subconscious thought process. Our value proposition is convenience. Customers can order items from the comfort of their homes and have it delivered to them. Also, the entire supply chain is controlled by Bigbasket. We don’t outsource at all. That ensures quality. For grocery, it’s very important to have instant and safe deliveries unlike regular couriers. It requires things like cold storage, etc. We have chillers and freezers in the delivery vans and we deliver even ice creams. There is a huge demand of chilled and frozen items today.

Of course, some people are set in their ways when it comes to shopping offline. Habits take time to change. However, the success of e-commerce players has shown that customers are open to try new things and gradually adapt to change if it makes their life easier.

We are currently aiming at 25 cities, and we don’t plan to expand in the near future. We are fully operational in 21 of these cities, and will cover the remaining in the next few weeks.

There are two types of models in the online grocery space: You either own the inventory or you use an on-demand, hyper-local model, where once the order is placed, contact is made with the supplier and the product is sourced. The on-demand model will see a change. The more control you have in this space, the better you can deliver. If you do this through an outsourced partner, there will be some issues. Also, if you own the inventory, your gross margins will be better, rather than sharing with a partner. There are certain items for which a customer goes to a specific store to buy them. For example, a lot of people say, “I will buy bread only from ABC Bakery.” So, what we want to do is create a marketplace for specialty stores. If you are coming from a particular pin code, you would be shown stores only from that area.

All our models are actually inventory-led. We never go and pick up from neighbourhood stores. Financially, commercially, economically this model doesn’t work for us because of margins, quality, etc. You get dependent on someone else’s quality, availability and the same margin will now get shared between two people. For these reasons, we have decided to control the entire supply chain.

There has been tremendous impact. Consumers buy grocery basically in certain ways. They have a planned buy. Grocery is the only item for which you have a list. You will decide what to buy during the week and then buy over the weekend. This is the category we have been in since we have started. Planned buys are normally the large buys that customer does. Average number of items that a planned buy basket has is 26 items/products. And in the beginning of the month it can go up to 50- 60 items, depending upon the size of the family. This business cannot be delivered on two-wheelers because they are large. It is not possible for us to send two-wheelers because then we will have to send some 15 two-wheelers to a house to complete an order. This is basically the first part of our model which we are doing currently. Around 60-65 percent of the orders happen through this manner.

Second thing a customer does is buy emergency items or things like fruits, vegetables and meats, which typically because of low shelf price, is bought more often in a month. It means that such items get over before the month end. These are the orders we are targeting with our one-hour express delivery option. We want the customers to try this service rather than walk all the way to a grocery store. I am happy to say that the adaptation of the express delivery option has been phenomenal, upwards of 70-75 percent of our existing customers. The overall volume of purchase has also gone up. So far, we have achieved 99.3 percent on-time delivery. Presently, we have time slots within which we promise delivery.

It’s only been a month since we launched the service. There is a long way to go but we are happy with what we have seen so far. In a Tier 1 town, the value proposition for the customer is time. In Tier 2 towns, that won’t be the priority. If you want to succeed in a Tier 2 city, you must provide them products that they don’t get there easily. If you just offer them the same products that are available in the local markets, they would much rather prefer to go out and buy them, as there is no problem of traffic nor are they pressed for time. Assortment is more important there.

It is about 13 lakh and rapidly growing. At the last count, 80 percent of our customers were female. Our marketing spends have been low. We are largely dependent on word of mouth. In Bengaluru and Hyderabad we have been targetting clusters of buildings/gated societies. We do events, distribute fliers, and convert a couple of people. After that the word spreads. Residents of societies are normally connected on an intranet, as a result, good news goes viral. For instance, someone put us up on the Bangalore IIM Alumni website. So long as we can deliver—going viral is good for business. The bad news is that if we mess up—there is a danger of that going viral too.

One thing that has not changed in all these years is the inefficiencies in the supply chain. But that is a universal challenge. There are other challenges which are specific to our online format. In the online space, people expect 100 percent satisfaction. If even one item is short they crib that they have to now go to the market, whereas if they were buying offline they could look for substitutes or go to another store.

Earlier, sometimes the picker picked and packed the wrong product. However, this has now been addressed. We have invested in special scanners which record the order and if the picker scans the wrong product the scanner shows the error.

Presently when we send goods, the delivery boy is taken straight into the kitchen. This has its own requirements. To minimise the time spent, the uniform for the delivery boys is sandals since these are easy to slip out and slip in. It also saves the danger of smelly socks. The delivery is done in open cartons, not plastic packets. But still the process takes time and the delivery boy is held up till the process is completed. We now want to tell the customer that they should trust us on account of our sophisticated systems. If there is a problem that arises, call us and we will give a refund. The purpose is to save time for the delivery boys.

The most difficult products we work with are perishables like fruits and vegetables. To combat that we have built collection centres at the farming locations themselves, where we immediately take possession of the farm foods and initiate the process of delivering them to the consumer. We have also appointed agronomists who work with the farmers and guide them in ensuring the best output for the crops.

“I am happy to say that the adaptation of the express delivery option has been phenomenal, upwards of 70-75 percent of our existing customers. The overall volume of purchase has also gone up. So far, we have achieved 99.3 percent on-time delivery”

Right now we have 15 collection centres, which should go up to 22 soon. We have a mix of organic and non-organic collection centres. We buy the products on location at the farms, and transfer them to collection centres. This way, we are reducing the number of middlemen between the farmer and customer.

Sixty percent of the fruits and vegetables we sell come directly from the farmers, and this percentage is set to go up to 80 percent soon. We have certain products like onions, oranges and apples, which come from a central place. Our onions come from Nashik, our potatoes come from Agra, our oranges come from Nagpur and our apples come from Shimla. These our single-point collection centres for the entire country. We call them ‘national sourcing centres’. These sourcing centres have a lot more holding capacity then collection centres. Intotal, we have 60 national sourcing centres and collection centres put together, and they are set to increase to 80 in the near future

The market for organic foods is huge. They literally fly off the shelves. That is why most of the times they will be out of stock on our website. There is a tremendous gap between supply and demand for organic foods in India. The reason for that is that you have to find sufficient suppliers, then get those suppliers certified by government agencies. We are actually trying to work with the government to streamline the process. Organic is poised to be the next big revolution in the country; it is only a matter of time.

Let me give you a sense of our overall numbers. We closed FY 2015-16 with revenues of Rs.700- 800 crore. For this year, we are aiming to at least triple the revenue and customer base.

Unfortunately, no. The supply sources are still the same. For example, we buy onions from Nashik, and if there is a supply issue on that end, it will affect all platforms equally, online or otherwise.

No, we are not. Our focus is in the online space and we do not want to deviate from that. If you try to do too many things, you might not succeed in all of them.

There is very little wastage. The difference between our online model and the store model is that we have only one stocking point, from where the food is delivered directly to the customer. The scope for wastage is therefore minimised.

By Neeraj Varty