Former civil services officers and now leading lawyers Abha and Y P Singh excelled in their respective professions and made a mark—sometimes to their detriment—as honest officers become uncomfortable colleagues for the corrupt. But they stood their ground, balancing their act through integrity and pragmatism, be it as professionals, parents, even as in-laws

YP Singh, an officer of the Indian Police Service, 1985 batch, Maharashtra cadre has done his masters in Economics and is an LLM gold medallist from Mumbai University. He has served in a number of stormy positions in the Maharashtra State Police, Food and Drugs Administration, and the Central Bureau of Investigation. Singh quit the police force in 2005 after serving for about 20 years. He has since taken to the profession of law. In a short span of about 10 years, he has excelled academically as a lawyer.

A firm believer in the power of integration, he is considered to be an authority on issues which have simultaneous implications across civil, criminal, statutory and administrative laws. Among others, his opinion is frequently sought by the media on a multitude of complicated issues relating to law and the government. His long stint in the bureaucracy, an intense bout in investigation and his expertise in diverse areas of law give him a unique position.

A prolific fiction-writer, Y P Singh has authored two books. His first book, ‘Carnage by Angels’, deals with the complex mechanism of corruption in the police department. His second book, ‘Vultures in Love’ traverses through the intricate socioeconomic dynamics specific to the government, against the backdrop of the services—income tax, customs and the Central Bureau of Investigation. His father served as Deputy Director General, All India Radio.

Abha Singh is a renowned lawyer, specialising in human rights, women’s issues and crime. She is a former civil servant currently practising as an advocate at the High Court of Judicature at Bombay. She is a renowned social activist who has done considerable work in the realm of women’s rights, gender equality and justice. She did her schooling from Loreto Convent and graduation from Isabella Thoburn College, Lucknow, where she topped her batch. She has done an M.Phil on Child Rights from JNU, New Delhi and her LL.B. from Mumbai University. In 1994, she cleared the UPSC examination and joined the Indian Postal Service. Her father was a gallantry award-winning police officer. Her mother had the unique distinction of being the first woman from her village to attain post-graduation in 1961 from Allahabad University.

She worked as a Customs Appraiser at the Mumbai Custom House from 1991-94 and then joined the Indian Postal Service in 1995. During her stint as Director, Postal Services in Uttar Pradesh, she pioneered the usage of solar panels to power post offices—there by making advanced postal services available to the remotest of villages.

Once the husband and wife have decided to be complementary to each other, there is no question of abhimaan (pride); it’s a question of synergy. Rather than enhancing the problem, creating conflict, which leads to retardation of both, why not be complementary to each other, and make two plus two equals five? —Y P Singh

In North India, a swanky car is given as dowry to a bridegroom working in the civil services... So my mother had asked him which car he would like to have. He had replied that he would not like to sit in a car gifted by his in-laws —Abha Singh

Abha Singh was third runner-up and lead woman finalist in the Times of India Lead India Competition in 2008.

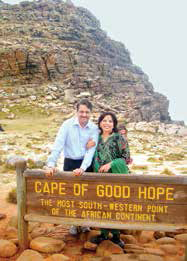

Both are dynamic in their thoughts and in their profession. Corporate Citizen spoke to them at length to get an insight into what makes them stellar professionals at work and a perfect match at home.

Well, it was on the engagement day!

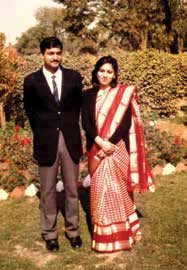

Says Abha candidly, “We both come from traditional Rajput families, and it was a choice made by our parents. We had not seen each other until our engagement day—January 14, 1987.’’

Adds YP Singh, “We were from a background where it was taboo for the girl and the boy to discuss marriage. It was our respective dads who talked about the proposal for almost two years.’’

At that time, Abha was pursuing her M.Phil in Child Labour from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), Delhi while her parents were residing in Lucknow. Says she, “One day, I saw my parents coming to meet me in college and my mom said, “Oh, I have bought an engagement ring and tomorrow is your engagement.’’ I was quite taken aback. My mom insisted that there can be no better proposal than this. She explained why. In North India, a swanky car is given as dowry to a bridegroom working in the civil services, which is considered an elite practice. So my mother had asked him which car he would like to have. He had replied that he would not like to sit in a car gifted by his in-laws. My mother convinced me that I would not get another boy with such exemplary character. She also told me he held very high values and didn’t drink too.’’

“However, my younger sister, who is now Commissioner, Income Tax, said, “We want to see the boy first!’’ I remember my father’s line. He told my sister, ‘ So you think you are so intelligent that you can question my choice?’ So he was my father’s choice as well.’’

Says Singh, “I had seen her only in a black-and-white photograph which was not very inspiring! Since I was getting hundreds of proposals, without thinking much about the photograph, I asked my parents to decide for themselves on this one too. It was my father who thought her to be the right choice from the very beginning—because of her family background, education, values and so on.’’

What was his impression about her when he saw her for the first time at the engagement? Replies Singh, “Of course, at that time, a person has some sort of scepticism. But it was like resigning yourself to fate.’’

Adds Abha, “My father-in-law had four conditions: she should be tall, healthy, beautiful, highly educated, convent-educated and with strong values. A lot of proposals were coming from girls who had studied in the Hindi medium. The convent-educated bit was a bit surprising, as the Ramcharitmanas which was broadcast every morning on radio was composed by my father-in-law. He was a senior bureaucrat, having retired as Deputy Director General of All India Radio. He died in 2007. Last year, his digitised Ramcharitmanas was released at 7, RCR.’’

Y P Singh was posted in Akola soon after marriage but Abha had spun dreams of appearing for the civil services. For Abha, it was a complete change of environment from urban Delhi to rural Akola. Says she, “I didn’t know Marathi. As Deputy Superintendent of Police, he was always on tour. There were no channels or cable TV then for entertainment.’’

Adds Singh, “And I had to drive not less than 300 to 400 km a day in the rural areas because there was a rule that if any murder took place, you had to be there two nights. So, working for 17–18 hours a day was the normal schedule. But that was fun.’’

Therefore, says Abha, “My only solace was books. I finished my M.Phil for which I came back to Delhi for a year. I had decided to take the UGC scholarship programme and got the scholarship the same year that I got married. At that time I was getting a monthly scholarship of ₹1,800 per month, with an annual grant of Rs.5,000 for books. I appeared for the civil services exam. In the first attempt, I got Customs and was posted at Bombay Customs. At that time I was pregnant and my son was born in October 1989. I worked for four years at Bombay Customs. When my son was four years old, I cleared the exam for the Indian Postal Service in 1993.’’

When Abha was appointed as Customs Appraiser, Singh took a transfer. Says she, “In fact, he used to be SP, Wardha those days—a post which came with a lot of fanfare and luxury. Despite that, he requested the DG for a posting to Bombay. And it was unheard of that an IPS officer asked for a posting.’’

Elaborates Singh, “At that time I was told that an IPS officer should not give a written representation for a posting. They said it didn’t befit the stature of an IPS officer to make a representation. That representation is made at the level of constables and sub-inspectors. Thus, I was compelled to request a deputation to Food & Drugs, which, I am happy to say, gave me a different kind of knowledge.’’

Abha got government accommodation at the Income Tax Colony on Peddar Road, while Singh’s posting at the Food & Drugs Administration came without a house or vehicle. Says Abha, with much appreciation for her husband, “I remember he would take a bus up to Grant Road and take the local train to MHADA. This is how he used to travel, despite being an IPS officer!”

Adds Singh, humbly, “Then I bought a Bajaj Cub scooter.”

But how did he feel, since he was an SP after all? “I don’t forget my past, it remains with me most of the time. During my college days, I used to drive a scooter. My father was given a house at Hyderabad Estate on Napean Sea Road. Sometimes I used to go to my college, Elphinstone College, on a scooter. So, I enjoyed this phase too.” “Our career thrives on observation and if you are moving in a four-wheeler, your observation gets constrained. If you are on a scooter you might suddenly see something weird in a slum, take a left turn, go into the gallis of the slum, analyse the behaviour, analyse the dynamics, because whatever we see, there has to be a history associated with it.”

Singh: “I always go by reason, not by passion—that is a one-liner I always follow in my life. Generally we see Westerners having these one-liners which become the beacon of their lives. So mine is very simple—go by reason, not by passion.”

Abha: In August 1991, when I was to join as Customs Officer, we decided to leave our son at my parents’ place, as it would have been too stressful to work as well as look after him. I visited my in-laws who were also staying in Lucknow. From there, we were to go to the station to take the train to Mumbai.

I still remember, my son was sleeping in the veranda, it was the month of April, maybe. My father-in-law had this in his mind that bureaucracy might corrupt me—in the sense that I would become powerful and arrogant and neglect my family and my husband. He held the impression that once women get power, the house breaks, a family doesn’t work. He wanted me to be a teacher. So he sarcastically said, “Yeh bechara Abhaga bachcha baahar so raha hain, isko maalum nahin hai iski mummy naukri karne jaa rahi hai, sarkari (this unfortunate child is sleeping in the veranda; he has no idea that his mother is going for work in a government office).” Turning to my husband, he said he was making the biggest mistake by permitting me to work. My husband may not remember this, but I remember it very well: he replied, ‘I am not going to impose anything on Abha. It has to be voluntary; if she doesn’t want to join, she will decide. But I will not tell her to leave her Bombay Customs job.’ He (my father-in-law) always thought his son quit his job because of me.

Singh: Once the husband and wife have decided to be complementary to each other, then there is no question of abhimaan (pride); it’s a question of synergy. Rather than enhancing the problem, creating conflict, which leads to retardation of both, why not be complementary to each other, and make two plus two equals five? This is what synergy is meant to be.

If you want to see that you are not victimised by corruption, take up the cause of honest officers. If you have honest officers, there will be no corruption and you won’t face any injustice —Y P Singh

Singh: “No, not a noble thought; it was a pragmatic thought.” Abha: And he didn’t regret it. I remember, those days getting a refilled gas cylinder was very tough. So once, a week passed by and both of us were struggling on a stove, cooking food. The gas agency guy would assure us that it would come that day, but nothing happened. One day, I got a little agitated, so I took a taxi and got the gas cylinder home. And then I remember having told my dad, what kind of situation I had put myself in. Leaving behind the comfort of an SP’s bungalow, where you had people to run errands, we were here cooking food on the stove, for a whole week. If it had been some other man, he would have made me resign, but my husband stood by me.

Singh: See, let me tell you frankly—the day I saw my dad retiring, I lost interest in government service.

Singh: My father held a high post, and was so passionate about his work that he wouldn’t take even a day’s casual leave. Every working day, he would be in office. And suddenly at 9 a m, on the first day of retirement, he found he had nothing to do. He became a wreck, in the sense that he could not bear that he had become a nobody from a somebody. The higher you climb, the harder you fall. So his fall was very hard. Then I said to myself, what’s this nonsense government service? And I quit.

Y P Singh works on all these five computer screens, simultaneously. Says he,“multitasking becomes easier as I can work on my legal cases, do research, see progress of our shopping mall in Lucknow and so on.’’ Unique, isn’t it?

Abha: I think his three year stint in the CBI was the most crucial phase of his career as he dealt with the Panna-Mukta oilfield scandal, the US-64 scandal (pertaining to UTI where about 2 crore people lost their money), Pavan Sachdeva case because of which the markets crashed. Instead of being appreciated for exposing these mega frauds, he became a bottleneck for the government. They repatriated him from the CBI.

Singh: What happens is that first they pat your back and once the case is successfully investigated, you become a villain. Your disposition doesn’t change, but the disposition of the powers that be changes. I have worked on the case, now I should push it still further, making sure the culprit goes to jail. At that time, the superiors change their colours like a chameleon. This includes the political bosses as well as your own bosses. I was there with the CBI for three-and-ahalf years. At CBI, you have to deal with complicated cases, corporate cases, etc. So it takes one year to comprehend. Then it takes another six months to build up the case by carrying out investigations. By the time you have cracked the investigation, these people see that they have a goldmine with them (using investigations to blackmail and extort from the accused).

Abha: In fact, if you read the book Polyester Prince written by Hamish McDonald, two pages have been dedicated to YP. It mentions that here is this young SP, CBI, who made a case on the wrongdoings of Reliance and when it became troublesome, was repatriated. They treated him in such a harsh manner. One fine day, the phone went dead. They disconnected the landline and it took three to five years to get it; there were no cell phones then. They didn’t want the media to get to him to know why he was shunted out. That was when we evolved. If we are the ‘dynamic duo’ today, it was because we withstood that time when we were being harassed, because he was an honest officer.

Singh: To put in a one-liner, to tolerate any injustice is a sin. If one person tolerates an injustice, the injustice gets multiplied. So I hit back and fought court cases against the government after I quit in 2005.

Abha: I had shed too many tears because here was a genius, a brilliant man unearthing such cases in the CBI, yet he was being treated badly. He penned a book and dedicated it to me and his father where he wrote, ‘To my wife, who believes, truth triumphs’. These were my values, I was brought up by a very principled father and I thought you cherish an honest man, you cherish his quest for justice. But here I saw a system which was out to destroy and trample. So that made us very strong. Today, what we are, is because of that struggle in the nineties. I was barely 29. And after what I saw in the system, we both decided to pursue Law.

Singh: I always see opportunity in adversity. Every adversity should be taken as an opportunity.

Abha: I would like to reiterate that the system is suffering because you never cherish an honest officer; you never stand by him when he is taking up your cause.

Singh: If you want to see that you are not victimised by corruption, take up the cause of honest officers. If you have honest officers, there will be no corruption and you won’t face any adversity or injustice. There are three types of criminals in India: 1) common thieves who steal, get caught and are arrested, 2) corrupt officers who rob the poor by filling their coffers from the money meant for government schemes for the poor, and 3) the worst, the ones who victimise honest people—because that kills the system.

Abha: He had quit his job and I was posted in Lucknow as Director, Indian Postal Services. I was allotted a beautiful bungalow with a garden in Hajrat Ganj. YP said, “I am not in any position to impose on you because I have myself quit my job, but for my parents, it would be humiliation that their only daughter-in-law is not staying with them but has opted to stay in a government house instead.’’ That sentence stuck in my mind and I opted to stay with my in-laws, although my daughter and my mother-in-law were not getting along too well with each other.

Singh: Marriages break because of non-application of mind and emotional frivolity. People these days are so intellectually frivolous. In marriage, one should go by logic and reason. That’s why in the West there are more incidents of divorce because they are logical. They feel if they are incompatible, better that they part ways, rather than pull along, cemented by some prescribed social norms.

Abha: No, but a marriage is of the hearts. I don’t agree that it’s all logic and reason.

Singh: A lot of women today say, we are not taking up jobs because we have to look after the children and that should be the first priority. I say, we also love our children. Both my children have grown up with babysitters. And both of them are toppers. My daughter stood 35th amongst the 30,000 students that appeared for the Common Law Entrance Test and my son stood 73rd.

Parenting is all about not having a very intensive intrusion into the lives of your children. Give them space, you only have to guide them to grow. You don’t have to push them. But you have to give them a lot of love; it has to be unconditional.

Abha: My mother-in-law would often say, if my son is happy, then I am happy with you, otherwise your achievement is irrelevant to me, and your achievements are meaningless if my grandchildren don’t do well. So I still remember, I would always tell my children that they are the real crowns on my head. The day they falter, all my success will be treated as zero, because they will say, oh, the mother wanted to be ambitious. That made my children go forward. Even today, my children are very responsive.

Singh: One of the values we follow is, don’t go by the dictum, ‘Spare the rod and spoil the child.’ Don’t go by that. Go by the principles of management. First comes individual initiative which is most important. Coercion never leads to any positivity. Coercion has to be done in a very restricted manner. Being coercive means losing your temper, behaving in an irrational manner. Some children tend to be obsessively idealistic. So if there is something obsessive in their thoughts, you have to be a bit strict to neutralise that. Because you know that at that particular point, logic does not prevail. Otherwise, let the children be on their own, let them study on their own, let them learn on their own. Just keep guiding. My son was fond of technology, so am I. When he was a child, I used to take him to the Dockyard every Sunday on my scooter. Then, I used to go along up to Vashi by train to see how that bridge was being constructed. My son and I, we would watch the progress. We would also see what size were the insulators, what KV transmitters, and how the electric cables were being laid. Every Saturday we would go to Nehru Science Centre and Museum. These are the effective collaterals which help in building up a child’s personality.

Singh: I would advise that you cling on to your principles. Conflicts will be there; don’t indulge in such conflicts too much because you are still very tender and it’s very easy to crush a tender person. So go with the system at a lower level, you won’t face too much of a resistance. The resistance will be manageable. But once you assume a bigger role, once you get profoundly anchored in the services, it is best to stick to your principles and stick on for some time, because if you stick on for very long, you won’t survive. Then you will be marked and dumped in inconsequential positions where there is no work. In every government service there are dozens of such positions where a person can be posted and he will be without work – a way to clip his wings

There are two kinds of officers – one says no, I will maintain my personal integrity, but it’s not my job to ensure the integrity of others. He is a passive officer. And the other— the active, honest officer is the one who says, I will be honest and I’ll make others honest too. Passive honesty does more harm than good.

The civil service is the spine of the country and the government is the biggest NGO. If we are able to make the systems work, then all the corrupt persons will fall in line —Abha Singh

Singh: We are going downhill. If we are able to stop this slide, that itself would be an achievement. But instead of stopping this slide, we are working to make it worse. Materialism is intense. The passion for money is enormous. Values have crashed. Our values are there with us only so long as we visit a temple and pursue our superstitions. But we totally forget our values once we are out of the temple or out of a spiritual discourse. Hedonism has captured the world. The principle of Hedonism is that we live for pleasure. So unless and until there is change in values, things won’t improve and to change these values, there has to be a very robust system, like it’s there in the West. In the West, they have values because they are intellectually advanced; here, we are intellectually primitive.

In my book I have discussed the concept of the ‘paradox of intelligentsia’. About 4 lakh, very high academically brilliant people try to get into the civil services, and the first 100 are chosen. Obviously they are the ones who are enormously intelligent. Since they are so intelligent, you expect them to be honest. However, the same intelligent person becomes a wicked guy once he is in the power game. If an intelligent person becomes vicious, he uses his skill to meticulously destroy the system. That is why our country is lagging behind in so many ways. We do not grow beyond seven to eight percent per annum GDP, when we can easily grow 11 to 12 percent. That minus four percent growth is because of corruption, inefficiency, lack of intellectualism. We only know how to praise ourselves, fooling ourselves about our intellectual or developmental growth. It’s the social welfare index which is getting undermined.

Abha: My take is, the civil service is the spine of the country and the government is the biggest NGO. Forget corruption. If we are able to make the systems work, especially investigative agencies like the CBI, the Anti-Corruption Bureau, etc, then all the corrupt persons will fall in line. But when your anticorruption system becomes corrupt, there is no fear of the law. In the West, there is minimum human interface. If you are speeding, it is the camera which will catch you and your ticket comes to you. Here, if you are speeding, your traffic constable comes, you give him Rs.100, you go scot-free. No lesson is learnt. If you ensure that the government personnel performs his job properly, governance will improve.

BY VINITA DESHMUKH