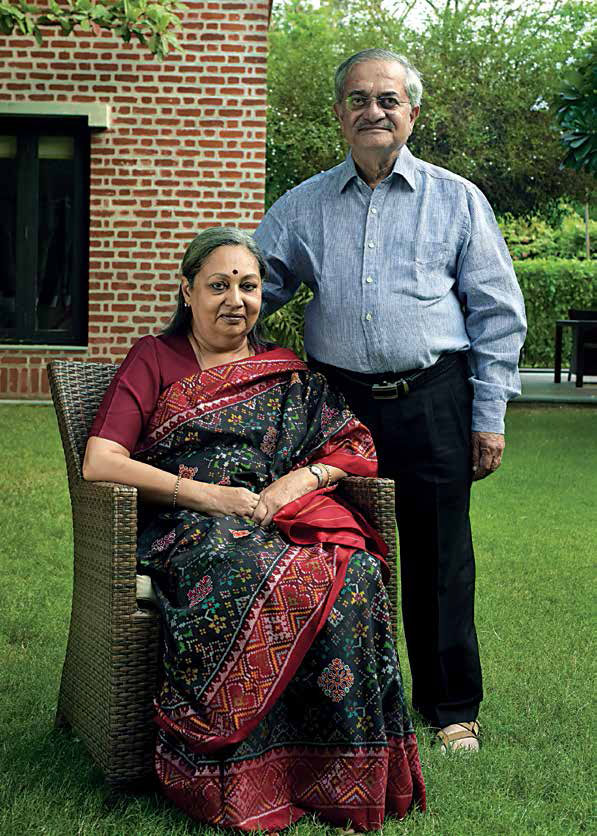

Shruti Shroff, Managing Trustee, Shroffs Foundation Trust, and Atul Shroff, Managing Director, Transpek Industry Ltd, are working hand in hand to change the lives of tribals in and around the forests of Chhota Udepur near Vadodara. From a small NGO offering health and medical services, SFT has grown into a multi-sectored organisation, empowering communities in a variety of areas such as watershed development, good farming practices and self-employment. These are in addition to Transpek's own range of core and CSR activities that include producing livelihood-relevant chemicals, education, skill development, vocational guidance and training-which together have helped improve the lives of 3,00,000 people in over 400 villages in the region.

The time, 30 years ago. The place, Vadodara in Gujarat. The Shroff Foundation Trust (SFT), administered by Atul G. Shroff, managing director of chemicals manufacturer Transpek Industry Ltd, and his family, was given a plot of land near the Transpek factory at Kalali village on the city's outskirts. Atul and the others planned to set up a super-specialty hospital on it. His wife Shruti, then 36 year-old, objected. What, she asked, was the need to spend so much? She argued that they should set up just a small hospital to look after the local people's basic medical needs.

Atul, who has been the MD of the family-owned company since 1981, has expertise in specific functional areas of the industry with wide business experience. He also served as Chairman of Transmetal Limited until January 2008, and has been a Non-Executive Director of the parent Excel Industries Ltd since August, 26 1994. Besides Transpek, he serves as a Director of Ace Zipper Industrial Co, Benzo Petrochemicals, McNally Sayaji Engineering, Nascent Chemicals Industries, Onix Industry, Punjab Chemicals & Pharmaceuticals, Sayaji Iron & Engineering, Shri Dinesh Mills, Transpek Marketing and Transpek Metadust. He has also been a Director of Punjab Chemicals & Crop Protection, Shree Dinesh Mills, Transmetal and TML Industries, and a Non-Executive Independent Director of Banco Products India.

Each project at SFT has been like a child to be nurtured, each being a very special and joyous experience. Through the SFT team my hands have multiplied manifold -Shruti

Shruti, who speaks Gujarati, Kutchhi, Hindi and English, is now Managing Trustee of SFT. Her work with the Trust began in 1986 when, she says, she and her team did not even have a clear vision of how their work would progress. "We were sketching our path step by step, gradually turning dark into light. Our struggles were many but today we have reached a point of clear vision thanks to all our supporters and well-wishers who contributed greatly by continuously motivating us and also providing monetory support," she says after more than three decades. "Each project at SFT has been like a child to be nurtured, each being a very special and joyous experience. Through the SFT team, my hands have multiplied manifold."

Along the way, Shruti has been mentored by-and worked closely with - leading nationalist K C Shroff, her father-in-law Govindjee Shroff and renowned socialist activists Nanaji Deshmukh, in various aspects of Rural Development. She also learnt Management, tutoring under renowned Gurus G. Narayana, Dr Shrikanthaiya, Dr M H Atreya and Dr Nanudiah. She was also mentored by Rolex Award winner Chanda Shroff in the revitalisation of indigenous crafts. She has trained in hospital management and the management of dialysis units under the experienced guidance of Dr Nandini Gandhi at C.C. Shroff Memorial Hospital in Hyderabad; in the management and implementation of rural development projects at the Administrative Staff College of India. The tutelage of Swami Jitatmanand and Swami Atmasthananda in the 'service before self' work ethic of the Ramkrishna Mission also led her to work as a voluntary teacher with the leading Baroda educationist Savitaben Amin.

Over the years, she has actively dedicated herself to the total development of vulnerable, impoverished and marginalised tribal and rural communities living in Gujarat, through natural resource management and revitalisation of indigenous resources-human, natural and cultural. SFT has grown from a small NGO providing health and medical services in the vicinity of the family industry to a multi-sectored organisation catalysing holistic and sustainable local development through, interventions that focus on empowering communities through capacity building and the development of regional institutions.

And it all began with her opposition to the multi-speciality hospital and advocacy of a small one. "The next thing I knew, I was invited to a meeting of the Trust Board, at which my father-in-law told me to go ahead with my idea!" she recalls. "He told me the Trust would put Rs.two lakhsat my disposal to do it." So she did. And that was the beginning of the story of Shruti 'bhabhi', who went on to become the Managing Trustee of SFT, subsequently expanding not only her brainchild Ramkrishna Paramhans Hospital - which gives free consultancy and diagnostic services as well as heavily subsidised surgery, dialysis and other in-patient facilities-but the scope and geography of the Trust itself.

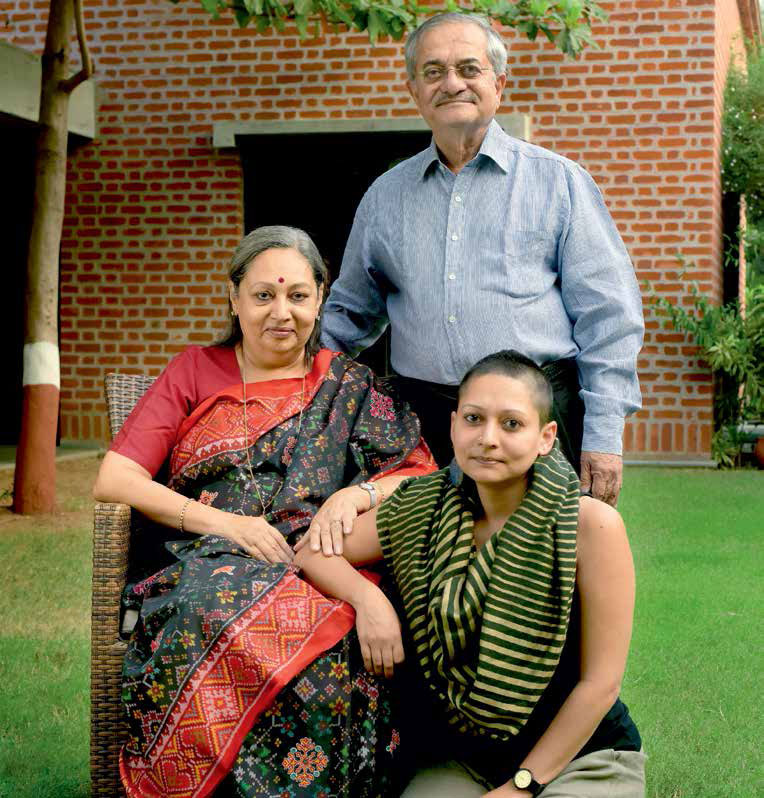

How did she decide that a scaled-down version of what was proposed would be good enough? "I am a mother!" she explains simply. "I know that if a woman wants nine children, she will find her own way to bring them up." She and Atul have only one child, a daughter. But Vishwas Shroff had her own set of difficulties, with an eye problem and dyslexia when she was in school - which she and her mother worked together to overcome. Vishwa Shroff, who is now a fine artist and a Cordon Bleu chef, married a Japanese architect, Katsushi Goto, whom she met and fell in love with when he was with her family for eight years, working as the assistant to the main architect who designed and built their new bungalow, 10 km from the city.

Shruti, who terms beadwork and cross-stitch embroidery as 'meditation' and lists them as her special skills and hobbies, was a Bombay girl who regularly did well in her studies, winning a gold medal in her B A Philosophy at Bombay University. Her marriage into the Shroff family, which runs the Excel Group of industries, was an arranged one. "That was the first time I went into a temple," she grins. After that, she could have been a socialite. Once she went to Vadodara and saw how the people outside the city lived, however, she chose to become a social worker. Her first visit to the forests of Chhota Udepur, and her close-up observation and experience of the tribal forest-dwellers' lives only strengthened her resolve to make a difference.

She still remembers that first visit. "Everybody advised me against going, because the tribals were reputed to be violent people who resented any outsider. Even government officials never ventured into the forests without an armed escort," she says

She still remembers that first visit. "Everybody advised me against going, because the tribals were reputed to be violent people who resented any outsider. Even government officials never ventured into the forests without an armed escort," she says. "But I had my mind made up, and went. We came to a shallow stream, and I had to pull up my sari to wade across. When I reached the other shore, there were some men standing there. I held out my hand, and one of them willingly extended his hand to help me climb out of the water."

That bridged not only the two shores separated by the stream, but the people on both sides. One of the women invited her into her hut to eat with them. Shruti tried to put her off. "How can I deprive her family of food they obviously couldn't spare?" she thought. But the woman insisted, so she had to go in and share their 'lunch'-which, she found, was jaggery mixed in water. "That's all they had," she shivers.

It also struck her that there were none of the usual sounds one hears in the forest: the silence was total. She remembers thinking, "Where were the chattering monkeys and chirping birds in the trees? The barking, growling dogs running around on the ground? Then it hit me: the poor tribals had eaten all the wildlife. But their spirit was strong; so was their sense of what was the right thing to do when they had a visitor-they must share what they had." This act of selfless hospitality prompted Shruti to take on a task a Gujarat government official had suggested: work to uplift the people of the area. She saw her efforts succeeding when, a year later, the same woman gave her a proper meal of 'bhakri' (a coarse roti) and vegetables.

The role of SFT is that of a catalyst, a facilitator providing the community opportunities for development, a mentor that guides them through the development process

The other half of the Shroff couple, Atul, became Managing Director of Transpek not by virtue of his birth in the family, but has grown through the ranks of the company to occupy the corner cabin only in 1981. "The Excel Group began as a kitchen laboratory, which my father and uncle set up in 1941 at Jogeshwari in Bombay to create pesticides that could help improve farm crops and solve the then prevailing food crisis. They eventually set up six different companies, which my father decided would be distributed among me and my five brothers and cousins, with all of us having joint investments and directorships across them," he says. The Shroffs being philanthropic people, they also set up half a dozen non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to help solve the problems of the people around each plant. Thus was born SFT, for Atul's company.

Known widely as a people's man, he is usually not in his cabin, but moving on the shop floor, strengthening his direct rapport with most of the workforce. With his deep understanding of chemical processes and his vision of developing Transpek into a world-class company with a global network, he has spearheaded the development of several innovative and appropriate improvements in Transpek's plants. "We have seven plants across Excel, employing 3,500 people, but we all produce different chemicals-so we don't compete with one another," he says. "On the other hand, we complement one another by exchanging knowledge and doing marketing for one another."

Transpek, which has grown to a turnover of Rs.260 crore over the past 35 years with Atul at the helm, has harnessed the most innovative and appropriate technologies for manufacturing chemicals with complex chemistry that also ensures due concern to the environment and safety of all employees and the neighbourhoods. "Like most businesses, we too went through difficult times before I hived off the sulphoxylates business to a joint-venture company, Transpek-Silox Industry Ltd, and built it up into a self-sustaining organisation of international standard," he explains. "But I continue to provide entrepreneurial inputs, adding products that have new applications and arranging synergies through both backward and forward integration to improve in-house generation of important raw materials and increasing in-house consumption of existing products. Today, our products are all world-class: for example, our thyonil chloride capacity of 80 tonnes per day makes Transpek the biggest Indian producer of this raw material for chemical weapons."

On the home front, Transpek has come up with a soil testing kit that Atul says "even Shruti's tribal people can use themselves", to analyse nine parameters within 24 hours and say how good the soil is.

This costs Rs.50 per sample, as opposed to the government's system for which they need to pay Rs.150, and get the results only after two months. After the Vadodara floods of 2014, Transpek also came up with a kit to test water potability.

"You pour the water into a small bottle, and it turns black if it is not fit to drink," he explains. "This is actually something Shruti wanted 10 years ago! It took a lot of time, trouble and money to perfect, but my scientists and I worked on it without giving up.

We manufactured four million bottles at Rs. eight each. The aim is to make the villages self-sufficient, as they used to be 200 years ago."

Today, with 60 cows on an attached farm, the cow dung is used to culture worms that are 'happy' feeding on the E. coli bacteria in it and power Transpek's organic ETP. The two plants set up with the unique worm-based process can treat 120 tpd of effluent

Beyond business, Atul has overseen the planting of 35,000 trees on 40 acres the company owns, and the setting up of a 7,000 litres-per-day water recharging facility for the two wells, two lakes and six borewells on the property. "We have not bought any water for eight years now," he says. "My uncle wanted to establish an effluent treatment plant (ETP) right since 1973, but the chemical engineers he hired used to run away because they were taunted as 'gutter mukaddam'-till he tripled their salary!" Atul says. Today, with 60 cows on an attached farm, the cow dung is used to culture worms that are 'happy' feeding on the E.coli bacteria in it and power Transpek's organic ETP. "The two plants we have set up with our unique worm-based process can treat 120 tpd of effluent," he adds.

Transpek continues its own corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, including vocational workshops for village children, scholarships for employees' children and awards for meritorious students in the villages in and around its plant at Ekalbara. It also manages the Industrial Training Institute (ITI) at Padra under the Union government's public-private partnership scheme, and is, according to its annual report, "actively engaged with science, engineering and management institutes of repute in Vadodara and Vallabh Vidyanagar to orient students to various industrial aspects". As Atul explains, "We are following my father's basic value system, which says that at least 10 percent of our income must go to society, preferably starting with needy neighbours."

Shruti herself recalls having been approached by the then rural development secretary Gopalaswami, who knew what she was doing in rural areas and asked her to work with the government. "But I didn't want to work in a corrupt system, so I turned him down. But he was very persistent: he eventually managed to rope me in, persuading me that only people like me could help the government's schemes to succeed."

As with most NGOs, her 'entry point', was watershed development, for which funds were available in Chhota Udepur. Gujlabhai in Ferkuwa village still remembers how Bhabhi did two projects for them, and taught them how to do it themselves. "We are no longer in lift irrigation, since the grants now go directly to the village panchayats instead of NGOs; but I still visit them," she adds.

She still remembers that first visit. "Everybody advised me against going, because the tribals were reputed to be violent people who resented any outsider. Even government officials never ventured into the forests without an armed escort," she says

Shruti and her team also taught the villagers how to select the right crops that would grow well on their land. Says another farmer, Ganjibhai: "Earlier, we used to bring assorted seeds in a bowl and sow them all; some grew, some didn't. They showed us how to plant only two or three that would grow, and to intercrop. We get a much better yield now." The trust's initiatives in agriculture, for which Transpek and its sister companies contributed supplements, pesticides and inputs, yielded tangible benefits, including the reduction of migration of villagers. As many as eight or nine out of every ten used to go away to work in other areas as farm labour. Today, most of them stay at home, and have multiplied their farm income thanks to SFT's intervention. Along the way, Shruti helped set up milk collection centres and established the Baroda Dairy the viability of establishing a 10,000-litre bulk chilling plant at Chhota Udepur.

After the farmers, their womenfolk: Atul's aunt Chandaben Shroff, who runs an organisation named Shrujan that promotes traditional embroidery in Gujarat's Kutch region, helped train them in Kutchi embroidery. Beginning with 40 of her village women, she got them trained to work on small job orders for products like cushion covers, bags, borders, purses and patches. This initiative has grown into the Shardadevi Co-operative Society, which has outlets to sell its 'Viveka' brand of handicraft products in major cities including Mumbai, and conducts exhibitions all over India.

"There are some 16 kinds of embroidery that the women in Kutch do," Shruti says. "The one Kaki chose to teach our women was that of the Mutwa tribe, which is a very difficult one. So I suggested that we start with Ahir, which is an easier type-but Kaki said, what difference does it make, when the women here don't know which is more difficult!" Today, the experiment has been so successful that not only are the products sold at the Shardadevi outlets, but Atul says: "I make sure that I carry a number of the items, like cloth visiting-card holders, whenever I travel abroad to give away to my business contacts there."

SFT also started a school support programme and a business process outsourcing (BPO) training centre at Chhota Udepur in 2008-which began a commercial operation with a lot of data processing work for the state government. Vikas Vaze, who was then the site head for Aditya Birla Minacs Worldwide, a major initial customer, is now the chief executive officer of SFT. "We have come a long way," he says as he shows a vegetable cold storage the Trust got going at Chhota Udepur, to which it has added a ripening centre for bananas. "We started with potatoes, which we got farmers to grow in this declared 'non-potato' area-now the cold store is full of potatoes, and the government has changed its category to that of a 'potato growing' area!" The facility is also rented out to traders for grapes and other produce when there is space available, helping to earn some more money.

There were none of the usual sounds one hears in the forest: the silence was total. She remembers thinking, 'Where were the chattering monkeys and chirping birds in the trees? The barking, growling dogs running around on the ground?' Then it hit her: the poor tribals had eaten all the wildlife

Under her, SFT has grown from a small NGO providing health and medical services in the vicinity of the family industry to a multi-sectored organisation catalysing holistic and sustainable local development through interventions that focus on empowering communities through capacity building and the development of regional institutions. "Today, the Trust attracts a number of national, international and government collaborations for development initiatives in the region," she says. "Our annual budget had multiplied from the original Rs.two lakh to over Rs.18 crore for 2014-15, with a committed team of almost 150 professionals and a network of 100 grassroots volunteers groomed for the task of local coordination and servicing. Our major achievements in the development sector include an integrated development process, which has brought about measurable and visible improvements in the region. We have been able to significantly improve the quality of life of 3,00,000 persons in 412 villages: agricultural incomes have increased by 80 per cent, small and marginal farmers have more than doubled their income in successful programmes like, Project Sunshine and the Wadi, programme, and incomes from sectors such as dairy have grown substantially. And Chhota Udepur, which did not traditionally have a dairy industry, is on Gujarat's dairy map now."

Shruti has always taken an active interest in her husband's business, too. "We both go and meet the workers regularly," she says. About a decade ago, when the company was performing particularly well, she addressed them and requested them to give a day's pay or Rs.500 each every year, to help society. "They all agreed, and they stand by us through good and bad times," she adds proudly. "Even when the company went into a loss, they continued to support us - even the junior most worker has the feeling that he is supporting someone who is worse off than he is. They all feel joy in this."

Adds Atul, "The economy of this country is not in the cities - those are only consumers. The villagers are the real producers. So if I can help them, I am happy to support their basic needs and give inputs. That creates a win-win situation." He also bought a farm to understand his target group's problems better. "I did farming myself, and hired a B.Sc Agriculture graduate to run it with me," he says.

Besides Shruti's original Ramkrishna Paramhans Hospital at Kalali, SFT has also created several other medical and other institutions like the Shardadevi Medical Centres in the remote belts of Chhota Udepur and Banni, the Krushi Seva Kendra at Chhota Udepur to help farmers in the region adapt modern agricultural practices, and its latest, VIVEC, the Vivekanand Institute of Vocational and Entrepreneurial Competence, to groom tribal youth for the present-day job market. VIVEC, set up in 2014 to commemorate Atul's father C.C. Shroff's centenary on a two-hectare campus at Paldi about 25 km from Vadodara airport, offers 10 courses in subjects ranging from information technology to fashion technology to nursing. Shruti personally supervised the design, with the walls showcasing folk and tribal art from different parts of India. "We want to make it aesthetic but people-oriented," she explains.

A similar dual philosophy of combining training with industry guides the laboratories in the Centre: "The students will earn while they learn," she says. "For instance, the fashion students stitch uniforms for the next batch; those studying retail sales run the tuck shop on campus; those in the welding course make boards the electrician students need."

Shruti has prepared detailed training and implementation manuals drawn from SFT's experience in the field in the seven key areas of adult literacy, livelihood development, community organisation, pre-primary education, information education and communication (IEC), HIV/AIDS awareness and watershed management. She has also designed the Samaj shilpi grassroots activist programme to groom local youth to maximise the development of the region through extensive training, setting up some 50 Samaj-shilpis and training them. The Trust's emphasis, she points out, has been to identify, inspire, motivate and build capacities of local leaders through extensive training and exposure.

One crucial factor has been the process of change, preparing people for it and empowering them to play a leading role in directing the development initiatives in their own communities. "I believe the role of SFT is that of a catalyst, a facilitator providing the community opportunities for development, a mentor that guides them through the development process," Shruti says. "The results and targets achieved have been a by-product of this process."

SFT has successfully blended Gandhi, Ramakrishna Paramhans and Vivekananda's philosophy with modern science and effective corporate management and governance systems

In her firm belief that obstacles, difficulties and deterrents are to be taken as a challenge, she doesn't let these discourage her. One of her personal problems has been her health-a lung condition that necessitates regular use of an oxygen cylinder, which she keeps in her office and carries with her in the car when she goes on field trips. "That was why we built the new house, away from the city," Atul explains. "In Vadodara, Shruti had to use the oxygen cylinder almost 10 hours every day. Out here, amid the greenery and the unpolluted atmosphere, she is much better." Shruti, sitting next to him and looking at him as he speaks, nods in agreement.

Husband and wife work together to minimise mistakes in the field- which can be very costly in terms of retaining the community's credibility. "We ensure that all new ideas, particularly in agriculture, are tried at our own farm first," Atul says. "Any of our initiatives are introduced in the farmer's field only after ironing out any wrinkles that crop up in these trials. We actually bought a buffalo with a disease known as chakri ka rog, and kept it on our farm but didn't know what to do with it. God brings the right resources at the right time - a retired government veterinarian landed up at our house the next morning and treated it till it was cured."

The woman whose first entry into a temple was as a young bride now explains her belief in the synergy of a spiritual vision with professional, business and management practices. Shruti says seva, sadbhav and vikas-the spirit of selfless service, a firm belief in social justice, sustainable prosperity and progress, respectively, are what guide her. "I am deeply influenced by Swami Vivekananda's ennobling principles of practical Vedanta for the upliftment of the downtrodden and potential divinity of the soul. Gandhi's comprehensive idea of rural reconstruction that emphasised the economic, political, social, educational, ecological and spiritual dimensions has inspired me to develop a holistic approach to rural development. SFT has successfully blended Gandhi, Ramakrishna Paramhans and Vivekananda's philosophy with modern science and effective corporate management and governance systems," she explains, adding: "The operative strategy of the Trust is Sahaviryam karvah vahey-a Sanskrit phrase broadly translated as 'the joy of togetherness together we will achieve the best, together we will grow together we will prosper'."

Shruti's work has earned her a lot of recognition and a slew of awards, including The Times of India Social Impact Award 2011 in the NGO category for the livelihood sector. Atul, she says, has always played a stellar role in her achievements: "My husband has ably and enthusiastically aided me in my task. And the whole journey has been a lot of fun!" It obviously still is.

BY SEKHAR SESHAN