From being a Gentleman Cadet at IMA Dehradun to a tank man who volunteered for special forces to fight cross-border terrorists during the peak years of anti-insurgency operations in Kashmir to a personality assessor at Bhopal SSB centre to becoming a pioneering HR figure in India’s banking industry, destiny has led Anshul Bhargava down many unexpected paths. While serving the Indian Army, he was exposed to some amazing leadership lessons. After leaving the Army, he found these lessons just as applicable in the corporate sector. Today, as Chief People Officer at Punjab National Bank Housing Finance Limited (PNBHFL), Anshul has shown how a 26-year-old, loss-making PSU can be totally transformed into a profitable and fast-growing housing finance company. He shared some of these lessons with Corporate Citizen while narrating his eventful career-journey which began from Lord Krishna’s birthplace Mathura

The art of influencing people to willingly do what is required to achieve a goal is the essence of leadership. Very few know how to apply it in a complex business situation. Anshul Bhargava is one such. As Chief People Officer of PNBHFL, he exemplifies the ability to change things when change is hard. Using battlefield lessons he learnt during his 21-year stint in the Army, Anshul’s corporate journey of eight years reveals how team spirit, loyalty, enthusiasm and determination can help overcome obstacles and bring transformative changes. Having joined the Army at a very young age in 1987, he left it as a Lieutenant Colonel in 2008, and went for an MBA degree in HR from the Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta.

He began in the corporate world as GM (Head-HR & Administration) with a start-up, Asset Reconstruction Company of India Ltd (ARCIL), in 2008, in Mumbai. In his very first corporate encounter, he faced a big HR challenge because the business of ARCIL (a consortium of major public sector banks like SBI, PNB, ICICI and IDBI) was that of recovery, and required a team of very skilful financial negotiators who could recover loans from hostile retail borrowers and SMEs, but without being harsh and tough with the clients. They were also required to turnaround stressed loans and non-performing assets (NPAs) of these banks, running into thousands of crores. And he was the first HR guy of the company with absolutely no experience of corporate HR practices. Banks had already tried and burnt their hands in this exercise and, as HR boss, it was his job to build a team who could smilingly resolve and restructure NPAs from banks. How he did it is an exciting story.

Three years down the line, he moved to New Delhi to work as Chief People Officer for a 26-year old public sector housing finance subsidiary of Punjab National Bank, called PNBHFL, which provided housing loans and loans against property to its clients. Here the challenge was of a different kind: turning a typical, loss-making government PSU with lots of demotivated employees, to a fast-paced, profit-earning, corporate entity, without letting the business stop even for a day.

Earlier, in his over two-decade long innings in the Army, besides facing hostile armed infiltrators in the difficult J&K terrain, he also played a big role as a group testing officer of the Service Selection Board (SSB), measuring the officer-like qualities of aspirants, and thus building the cadre of the Indian Army.

Anshul Bhargava shares important landmarks of this exciting journey with Corporate Citizen, asserting that whatever success he achieved was due to the vital leadership lessons he learnt in the Army.

‘The art of influencing people to willingly do what is required to achieve a goal is the essence of leadership. Very few know how to apply it in a complex business situation.’

I belong to a small town, Mathura in Uttar Pradesh, where I did my early schooling. Mathura has a very big cantonment area. Initially it was more of a fascination but then I fell in love with the olive greens after a particular incident. In those days, the Army used to organise army melas annually in small towns like Mathura where they would not only display their equipment, tank models, trenches, underground hospitals and such other things but also simulate a war-kind of a situation for visitors. I used to go there with my elder brother who is now based in Allahabad and works as a senior designated lawyer at Allahabad High Court. I must have been studying in class second or third, but I still remember how thrilled I was watching those smartly dressed young officers explaining warfare techniques in simple terms to people visiting the mela. Memories of those army melas left me with the feeling that one day I too would don these olive greens.

When I was in class six, my parents sent me to India’s leading, all boys and fully residential, The Scindia School (TSS) in Gwalior (Madhya Pradesh), where this thought of getting into the Army got further cemented. At TSS, learning extended beyond the classrooms. The focus was not on just academics but also on discovering special talents in other areas.

I got exposed to a lot of co-curricular activities like debating, elocutions, athletics and so on. Being a keen sportsman, I also got a chance to represent TSS at various competitions and took part in a wide range of intellectual activities which helped me imbibe some leadership qualities. Besides taking part in NCC, I did a lot of horse riding there. TSS taught me how to think and become independent and helped me experience India’s diversity at a very early age because it attracted boys from all parts of the country.

I passed out from IMA in December 1987 and then I got into the Armoured Corps at Ahmednagar in Maharashtra. It’s one of the combat arms of the Indian Army and considered a dream for anyone to get commissioned into. They are popularly known as ‘Black Berets’. I was indeed fortunate to be commissioned in ‘Sattar’ Armoured Regiment, a very elite one as it had fought in all the wars. It has an ethos and culture of ‘Easy Efficiency’ and the motto and war cry of the unit is ‘Karke Rahenge’, which is self-explanatory. These values laid the foundation of my personality as it was my grooming stage where being the junior-most guy, initially, I was not permitted to get into even the officer’s mess and had to stay with my jawans. But that’s the way Army teaches you the basics of leadership because as a commanding officer, you have to know your men first.

When you join an army unit, you get into what in the corporate world is known as the buddy system. In the Army, it is known as the ‘senior subaltern’ who, in the good old British tradition, becomes your mentor, guide and philosopher. He is there, as they say, to ‘smoothen the rough edges of the diamond’ in his charge. He tells you to an extent, how to behave and conduct your-self, also guides you in your career path for about seven to eight months and then, of course, you’re left on your own.

In a typical fighting army unit -- tanks in my particular case -- you have support elements like the logistics, supply-chain, communications, transportation and the guy who co-ordinates it all, the adjutant of the unit. When the order comes, he is the one who steers the unit for the completion of the task by coordinating down below and the top. You’re also called the chief execution officer of the unit who gets all the orders executed effectively. That’s a prestigious appointment. The army trains you for one additional position too.

If you want to graduate to an instructor’s job, you’ll be sent for a specialisation course in that particular field. I specialised in tank gunnery warfare and then became an Armament Instructor at the Armoured Corps Centre and School (ACCS) at Ahmednagar where I had to train young and senior officers. There after, they sent me on different assignments including that of a brigade, as a Staff Officer.

Yes, after a while, I volunteered for the Special Action Group (SAG), a crack unit of the Indian Army involved with counter-insurgency operations in Jammu & Kashmir. I’d done well in the Armoured Corps, now I wanted to go and see other parts of the combat side of the forces. So, I underwent this gruelling, 40-days’ probationary commando training where I had to take off my ranks and do it just as a jawan does. There is no guarantee that you’ll succeed because the selection rate is just about two percent to become a Special Action Group Officer! I did well and so I got a chance to take part in the core insurgency operations in J&K for three and a half years on mission specific tasks.

I came back to my unit as the second in command, organising training and taking care of everything else. It was around this time that I was selected for the SSB. It’s interesting to know how the army does it. It keeps a record of your selection days, when you got selected for the army, how you performed during your own SSB. If you did extremely well then, you are called for a course to be trained as a personality assessor or a Group Testing Officer. Then you’re taken through a theoretical phase at the Defence Institute of Psychological Research (DIPR), an off-shoot of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), based out of Timarpur in Delhi, where you are taught psychology about human personality and behaviour and the various techniques to gauge them.

That’s right. But it’s also true that you’re successful in the Army if you understand people and their personalities. You need to understand the junior-most jawan, his background, his education, his family, his mental state on a particular day. When you’re going on a tough operation and if he is distressed on that day, then you’re asking for trouble -- you can’t take him for that operation. You need to first motivate him.

‘You’re successful in the Army if you understand people and their personalities. You need to understand the junior-most jawan, his background, his education, his family, his mental state on a particular day.’

While the army sees a person’s potential to become an officer, in corporate selections, we see where this guy is coming from. We ask him what he has done. If he says, ‘I’ve done this or that’, then we think he’ll perform with our product and within our cultural environment. Many a times we fail. We presume he’ll be a long-distance runner, but if his heart is somewhere else, he’ll not perform to our expectations.

I think so. As a selector, you predict his level. These records are maintained throughout the life-cycle of the officer. Whatever you write in your report; stays in the officer’s dossier throughout his life and for posterity in the Army archives, especially for generals. In the Army, we do a lot of analysis of your personality, irrespective of your branch, whether you’re an engineer, doctor, lawyer--everyone has to go through the SSB process and even after you get selected and go to your respective academy (NDA or IMA, OTS or whatever), we go back and validate our findings. How are you performing there is checked, and thus further calibration is done.

It was great because it gave me a lot of insight into human behaviour and how to leverage the core competency of an individual. It also gave me a lot of quality time to myself. That’s when I thought, let me put some hours to study, because by then I had already completed 18 years of service and wanted to move out of the Army. I had to complete the mandatory 20 years’ service so as to not to lose out on my pension. I was posted here in Delhi at the Army headquarters, managing the service records of the officer cadre of the Indian Army. That was a very fulfilling tenure where I got exposed to the dossiers of all the officers.

First I cleared GMAT and joined IIM Calcutta in 2008 to do its one year MBA program, PGPex or Post Graduate Program for Executives. I then got a campus placement at Mumbai-based ARCIL. So, this was my journey from the Army to the corporate world. I realised that the techniques I had mastered in the army would hold me good on civic street.

The Army is not a 10 to 5 kind of a job. If someone joins in today, you can’t fire him the next day. He stays with you for the next 20 years. So, you have to be extremely careful because the damage an individual can do to the organisation is immense. Hence as an assessor you need to do the job with great responsibility to build its officer cadre. Incidentally, since I had mastered the Army’s group testing technique which emanated back from the UK -I was made part of a study team of officers from the Army and DIPR that visited England when the Indian Army wanted to make some changes in this technique.

I was already 40. I had got commissioned when I was 20, so I knew that it was either then or never. Moreover, from 2006 onwards, corporates were looking for army guys, though in 2008, our economy suffered on account of the global recession.

I appeared for GMAT and my score took me there. The courses you just mentioned were small Management Development Programs (MDPs) of about a week’s duration and I was sent by the Army to attend them. There is an Army Training Command at Shimla which nominates officers to attend these courses. I was fortunate that I was selected to attend this MDP at IIM Ahmedabad in 2003-04 when I was an assessor, for a course on “leadership and change management”. Then I was sent to attend another MDP, on “effective communication by senior leaders and managers” at MDI Gurgaon. But PGPex at IIM Calcutta was a year-long program.

I attended these in-campus courses with other participants from the corporate world. In fact, that was my first exposure to corporate leaders. Since it was a seven-day leadership course conducted by IIM A’s senior-most faculty Dr Niharika Vohra, I rubbed shoulders with top CxO level officers from MNCs like Coke, PepsiCo, Cannon and others. It changed my perspective as to how the corporate world actually functions.

While I was trying to understand the corporate culture, they wanted to know how leadership works in Army. That was a great exposure for me. I made good friends there, did a lot of networking and kept interacting with them to learn on how I should move out of the Army and what should I do next. Thereafter, just before leaving the Army in 2007, another MDP opportunity on communication skills at MDI Gurgaon came my way and I grabbed it with full vigour. These MDPs were fully paid and sponsored by the Army which really helped me when I joined the corporate world. My family also backed me in full measure because they knew what it would mean to all of us and that helped me in leaving the uniform. These courses helped me in my smooth transition from the Army to the corporate world.

This I did while I was here at PNB Housing Finance. I wanted to become a certified assessment centre expert, so I did this week-long assessment certification course at XLRI, covering both theory and practice of the assessment centre approach to competency mapping.

‘While the army sees a person’s potential to become an officer, in corporate selections, we see where this guy is coming from. We ask him what he has done. If he says, ‘I’ve done this or that’, then we think he’ll perform with our product and within our cultural environment. Many a times we fail’

HR happens to be my core competency area as I’ve done personality assessment and officer cadre management of so many army officers. Moreover, thanks to the Army, I was able to attend very useful leadership courses at India’s top management institutes.

Since the Army groomed me to be a team member, I learnt the importance of being a contributing team player who can compete with the big guys while working in small teams with trust-worthy people in place.

They came to IIM Calcutta campus for inter-views and selected me. I joined it because I was the first one to be hired as HR head and I saw great HR opportunities in it. Being the first asset reconstruction company in the country, they were starting their retail operations by commencing the business of resolution of non-performing loans (NPLs) acquired from banks and financial institutions. It helped me play a pioneering role in setting standards for the industry in India.

It was a Mumbai-based financial institution made by a consortium of banks like SBI, ICICI Bank, PNB and such others who had sold their bad assets and NPLs to ARCIL which believed in handling issues rather differently. Unlike others who speak loud with their tough guys coming in to take over your assets, they work with a soft, resolution-approach. My role as HR manager was to build such a team by picking up people with the right temperament and attitude, grooming them not to have that hard approach, but to have a cultured one with customers. Also, I had to make sure they had very sound financial knowledge to restructure the bad assets, engage courteously with customers with flawless negotiating skills. They also had to be presentable, with good closure and relationship building skills. I had to groom these people into the required mould, knowing well that it was the first time that any company in India was doing this.

The task was to resolve issues related to Non-Performing Assets (NPAS) and get their money back. Banks had already tried and failed. I thought about it deeply and realised that customers of such an asset recovery company would interact with people with high credibility. I suggested to my management that we engage short-service army officers as branch heads. That was a major initiative. We hired a few short-service commissioned officers who had spent five years in the army. We got those young captains in independent geographies. When these guys told the customer that they were from the Army, the issue of credibility got resolved instantly. A rapport would be built with the customer in no time, helping them resolve his case amicably. This was also the first time that people from the Army got into this kind of job where they were doing core operations requiring enhanced soft skills. It was a win-win situation for both. In my three years tenure I was able to build a team of highly credible negotiators who turned the fortunes of ARCIL in a remarkably short time.

Oh yes. Before ARCIL, I had worked 21 years in the Army where even if you want to write a letter to someone, you just have to call a clerk and dictate. But the moment I stepped into the corporate world, even for a small memo, I had to do it myself. I was not used to it. Another problem was Microsoft Excel. I really struggled with it initially because I had never worked on stuff like that. One day I literally called back my wife who was in Delhi, and said, my biggest stumbling block there was not HR but Microsoft Excel. I gave myself one week and enrolled into NIIT’s evening program where I could learn Excel. I had to download the programs on Excel tutorials and for the next 72 hours, I slept for perhaps two to three hours at night. By the eighth day, I again called my wife and said, now I’m OK with it and this monster is over my head. So, that’s the kind of killing instinct which the Army gives you to cross over any hurdle that comes your way. I had to do it because these days, all data is Excel based in the corporate world.

See, in the corporate world, good work doesn’t go unnoticed. It gets spread by word of mouth. I got promoted from DGM to GM within a year because ARCIL started showing positive results within a short time. People started talking about an HR person who was instrumental in its turn-around. One day, I got a call directly from the MD of PNB HFL for a job opportunity in Delhi. Now, I always wanted to come back to Delhi because it was close to my hometown Mathura where my parents live, and my children were studying here in Gurgaon, so that was another attraction. I was also fed up with Mumbai’s traffic which involved travelling almost two hours daily just to reach my office. For someone who had spent his life in cantonments where you travel just one or two kms in a day, it was obviously a big pain every day. Yet when he made this offer, I said no, I’m not interested.

I refused because I thought it would be a typical 9 to 5-type, PSU job which I didn’t want to get into. I didn’t want a very secure, government job. I told him I needed a challenging assignment. But then he started explaining how this organisation was going through a business transformation process. He said it was a 26-year-old, fully-owned subsidiary of PNB Bank where people came on deputation from the bank to run it. They had a very short-term perspective, hence the company was not doing well. The NPAs were about 15 per cent and growth was hardly visible. At that stage one option being considered was to roll back the subsidiary into the bank, but that would have rendered many employees jobless. So the authorities at the bank and in the Ministry of Finance decided you couldn’t roll back a subsidiary, hence they went for a public-private partnership where 51 per cent stake went with the PNB Bank and 49 per cent was sold off to a private equity player. With private equity guys coming in, they obviously wanted the organisational culture to be changed—they demanded a complete business transformation from a PSU to a corporate entity.

When all this was explained to me, I could clearly see the opportunity that any HR in his lifetime would love to grab, because converting a typical PSU to a corporate was like changing the soul of an entity. You are changing, not just the work culture, but also looking at people’s transformation by bringing the existing lot on par with performance-driven employees of corporate entities. You had to get fresh talent from the industry and merge them with the existing cadre in such a way that they turn it into a performing organisation. So it was a complete change-management task in the true sense, where I was getting the opportunity to change people’s thought processes, technology, culture, ethos and value systems. When I saw this opportunity, I just grabbed it, even though it was a risky proposition, as one did not know how it would unfold.

When I joined here in August 2011, I knew I had to have winning teams. I needed the right set of people with the right cut of skill-sets to join the team to achieve high quality work. I needed people who were ready to stretch themselves beyond expectations and who were not bound by timings. But since I also believe in holding myself accountable to the highest standards, I led by example and got involved in its transformational journey.

In a typical PSU like this, resistance to change was obviously there because many felt that being an outsider I was trying to bring about a change in their lives. They used to come at 10 am and leave by 5 pm but now I had thrust a corporate culture upon them where performance was measured and they were accountable for everything. Even their government salary had been taken off and a cost-to-company with performance-driven pay culture brought in, and goals specified for everyone. There was a lot of resistance in the beginning. Gradually things changed, but primarily because of my Army background. Now I have been able to establish the much-needed trust and credibility which has helped me in building rapport and communicating with them in the language they understand.

‘The Army is not a 10 to 5 kind of a job. If someone joins in today, you can’t fire him the next day. He stays with you for the next 20 years. So, you have to be extremely careful because the damage an individual can do to the organisation is immense. Hence as an assessor you need to do the job with great responsibility to build its officer cadre’

Thanks to the exercise we undertook five years ago, PNBHFL has now become the fifth largest housing finance company and won a number of accolades. What we did was an open heart surgery with heart transplant. We transplanted the heart while the patient was alive and ticking. We continued to do business in the organisation and achieve the numbers while transforming it completely. The compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2011 to 2015, was 49 per cent, with a 30% profit after tax. The company had one of the lowest NPAs in this duration and customer service standards on par with any other retail lender. The total net worth of the organisation also grew by 48 per cent. The total net worth of the organisation also grew by 48 per cent. The loan outstanding – that is the total asset side of the organisation -- has grown at a CAGR of 52 per cent. So it has been a phenomenal growth journey in just four years. Today it’s rated as the fastest growing housing finance company where its transformation hinged on the HR taking the lead and leading it from the front.

I look for contributing team members who are open to learning, have the right attitude, clear vision and are culturally fit to become a performing employee.

They must have a detailed plan with timelines and key milestones identified as part of their business transformation agenda. Also, they must ensure buy-in of key stakeholders to drive adoption and long-term sustenance of change efforts. Assigning a key stakeholder as the sponsor of the intervention is particularly useful to facilitate this. They must remember that robust communication mechanisms are the key to negate the adverse impacts arising due to uncertainties and apprehensions associated with change intervention. Also, from the outset, all important “whats in for ME” needs to be communicated to all process stakeholders and both success and failures must be acknowledged collectively, ensuring accountability at all levels.

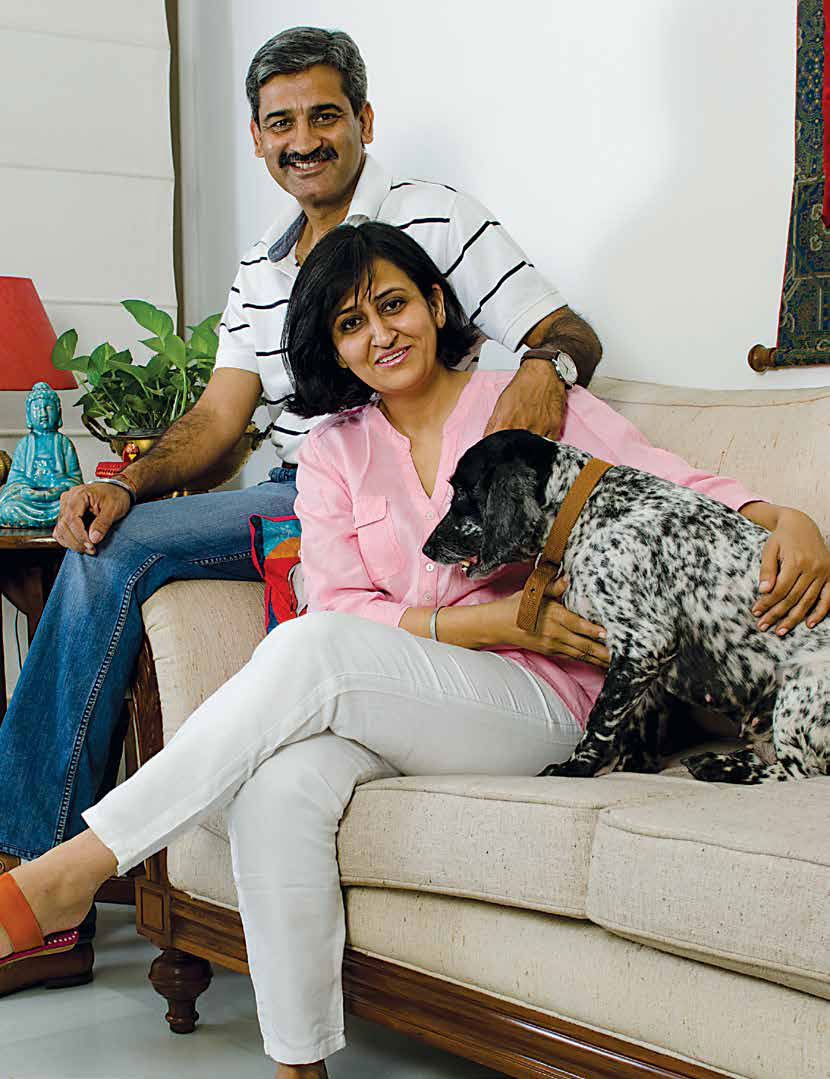

It wasn’t love at first sight, but 20 years after marriage and through the eventful journey of Anshul Bhargava’s military innings, their romance is still alive and kicking. While Anshul, now the Chief People Officer of PNB Housing Finance in Delhi, has a hectic life in the corporate sector, Radhika is busy with bird photography and teaching toddlers

With positive thinking, commitment to values and a vision, you can achieve anything and reach great heights.

People say, behind every successful man, there is a woman. But who’s behind a successful fauji? We can say for sure: Behind every successful soldier, there’s an even stronger braveheart—his wife. Nobody exemplifies this better than Radhika Bhargava. A freelance bird photographer, Radhika loves being in the company of toddlers: she teaches at an academy in Gurgaon (now Gurugram) and helps kids in the neighbourhood who need ‘a little guidance’. Marrying a fauji was not what she wanted initially. It involved ‘too much travelling’, the husband missed out ‘all the special stuff ’ like birthdays, anniversaries, even the birth of your child...So she wanted to marry a civilian. More so, being the daughter of a serving army officer, she had seen military life from ‘very close quarters’ and knew how it affected all your ‘big life decisions.’

“Anshul’s profile appeared in the matrimonial columns of the Times of India. When my parents pointed it out, I reluctantly said, okay, I’ll post my biodata but for this guy only.” The rest is history. “Everything went off very smoothly”. They met in February and married in August. Her parents were comfortable since in the Army, ‘it’s like a family’ and they could easily enquire about Anshul from his seniors. “Yet they were initially not aware that Anshul was a UP brahmin while they were Punjabi Khatris. They thought Anshul was also Punjabi because there are ‘Bhargavas among Punjabis’. But she was okay with it because she wanted an inter-caste marriage, and so did Anshul.

Radhika was studying at Lady Irwin College of Delhi University, completing her master’s in Community Resource Management so as to take up a career in India’s emerging development sector. But she didn’t complete it because Anshul, a major and senior squadron commander posted in Roorkee at that time, said ‘it wasn’t going to help her out’.

Post-marriage, they first landed up at Suratgarh in Rajasthan which was ‘very difficult to find even on the map of India.’ Was it a shock? “Not really. It’s a desert, a very beautiful place. I have very pleasant memories of Suratgarh, its sand dunes and our bonfire parties. From Suratgarh we moved to Pathankot in Punjab and in a year plus, we had a daughter and in another year, the initial operations under the Kargil conflict begun. Heavy tank movement was taking place between Rajasthan and Punjab.”

Did Anshul take part in the Kargil operations? “Yes, but towards the fag end. He had special training in mountain warfare. Anshul was moved to Chakrata, but by then Kargil was tapering off. But soon thereafter, he was part of Operation Vijay and Operation Parakram, the 11-month-long border stand-off that took place after the Decem- ber 13, 2001 terror attack on the Parliament.”

“At that time again we were in Pathankot, he was away for that operation. Then his squadron moved to Kashmir to check roads for landmines and improvised explosive devices before they were opened for the public. He was sent away to Kashmir and I had to be alone,” Radhika recalled.

What did she do then? “Since taking up a job was not possible in those areas, I worked with the wives and kids of jawans. These women came from small villages, they didn’t understand the language. I used to teach them, and help their children study,” she said, adding, “generally, these ladies were very good at knitting, so we gave them designs and helped sell them through exhibitions in Army areas. I had also taught them how to make candles,” she recalled. She also taught at school, up to class VII, and had begun bird watching and nature photography.

But she must have experienced all such tension earlier as an army officer’s daughter? “Yes, but from daughter to wife, it’s very different. Your emotional involvement is of a different level altogether,” she points out.

“Packing and unpacking household stuff during each of his postings—almost every two years—was quite frustrating. We used to live ‘out of the box’.

“My kids, especially Shagun, my daughter, could only associate him with his Maruti car. Any white Maruti would be papa because he would come in the evening and the next morning he would be gone. Out of the 10 years of my life with him in Army, he must have been out of the house for at least six to seven years,” she recalled.

Was there no peace-station posting? “It was only when he changed his subject of study and got into the SSB recruitment process at Bhopal that we got some relief. He spent a good four years doing and enjoying that.”

After Bhopal, they came to Delhi on compassionate posting because Anshul’s mother was unwell. “He was posted here at the Army Headquarters. When he was about to finish this posting, he was to be sent on a field assignment for three years. At that point, I put my foot down. We had stayed separately for very long. Shagun had gone into V class and three more years would be too much for me to handle. So, I said, it was time he put in his papers.”

It so happened he was completing 20 years in the Army. “We waited for a year and then he left.”

Soon after, Anshul left to do his year-long, fully residential MBA course from IIM Calcutta, and then joined ARCIL in Mumbai in August 2008, beginning his journey in the corporate world. “After the kids’ academic session here at DPS Gurgaon we too moved to Mumbai.”

In Mumbai the kids moved to a new school, Anshul was getting used to a new work environment, and Radhika resumed her bird photography.

Shagun, my daughter, could only associate him with his Maruti car. Any white Maruti would be papa because he would come in the evening and the next morning he would be gone —Radhika

“No. I did no course. I learnt it over the Net. Everybody used to discourage me because the lenses used in bird photography are pretty heavy, each weighing 2 to 3 kg. They said I wouldn’t be able to carry such heavy stuff. But I stuck with my hobby.”

Why did they choose to go back to Delhi? “The schools in Navi Mumbai, where we lived, weren’t very good so I wanted to go back to Delhi to a decent school before Shagun went to the IX class,” she explained, adding, “Fortunately, at that very time, the PNB HFL story happened.” Mean-while, Shagun completed her XII and Shubhankar, their son, will be appearing for his XII CBSE board exams this year.

Pips in Shagun, “I want to become a criminal lawyer, but they are discouraging me because we don’t have lady criminal lawyers in India. So, may be a corporate lawyer. I want to do my law from National Law School Delhi or Bengaluru. The seats are few, the entrance exam pretty tough, but I’m determined.”

Shubhankar, wants to become “a chef and later pursue a course in Culinary Arts from the US.” He is incidentally an avid watcher of the TV serial MasterChef Australia.

Besides photography, Radhika collects antiques and old brass kitchen utensils. “I’ve a fairly good collection. Wherever I go, I look for kabadi ki dukaan and ask them if they have any old items.”

What about Anshul? “Though he loves reading, he’s really a workaholic. He is still in love with his regiment, tanks, jawans. At PNBHFL today, he can die for his organisation,” says Radhika.

Does Anshul help her in pursuing her hobby?

“Oh yes, bird photography is very challenging. When you’re in a bird sanctuary such as Bharatpur or Asola or Okhla or Sultanpur, you have to go to areas where I can’t go because of the khaddas. I tell him what to do, he goes and clicks the pictures I can’t manage to. Anshul loves walking long distances and sharing his experiences with me, so he makes such jungle experiences very enjoyable,” Radhika signs off enthusiastically.

By PradeeP Mathur