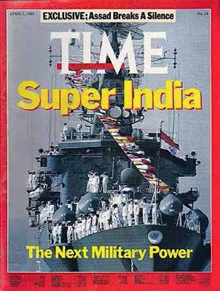

From designing the INS Godavari, India’s first indigenously built war-frigate to patrol vessels and tugs and then on to design the ubiquitous TVS Scooty, Capt N S Mohan Ram (retd) has been responsible for the ‘birth’ of many an engineering ‘vessel’ throughout his illustrious career, naval and beyond. In an equally eventful corporate career he turned around sick companies and steered many a corporate boat out of the storm. No wonder, he’s known as the Captain with the Midas touch who ‘sculpted’ vessels and companies alike

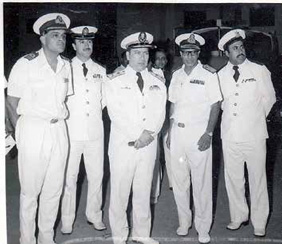

The warm and affable exterior belies the strategist at heart. For someone with a career span of nearly six decades, Capt N.S. Mohan Ram (retd) has juggled many a hat in his career in the naval cadre and beyond it. Lauded for his design distinction of INS Godavari (F20), he led the team of naval designers to construct India’s first indigenously built warship that stood in a class of its own amongst guided-missile frigates. He was awarded the ‘Vishisht Seva’ medal by the President of India for this feat. Capt. Mohan Ram’s versatility has had a ‘rub on effect’ on almost all sectors that he traversed, post his retirement from the Indian Navy. The ‘Captain’ with the ‘Midas’ touch has also been dubbed as a corporate ‘turnaround strategist’ as he set sail on his corporate sojourn in 1984 with a small loss making division of Mukand Ltd, with turnover of just Rs.1.5 crore. He managed to turnaround this sick unit. Following on this success, he was made to shoulder the responsibility of running the Rs.20 crore Mukand Foundry Ltd. This became the start for many new forays within the company and the wider corporate world. Capt. Mohan Ram designed the ubiquitous ‘TVS Scooty’, a winner of many design awards. His journey with Venu Srinivasan and TVS Motors Ltd since 1989 has been much lauded in the automobile sector. Currently, in an advisory role with the company, he pioneered and continues to extend his expertise on recycling end-of-life vehicles in India. His pioneering design of Offshore Patrol Vessels formed the backbone of the Indian Coast Guard, with nine of the class entering service. He also designed India’s first cycloidal propelled tug for Cochin Port Trust and India’s first diving support vessel for underwater exploration and repair. He led the team that installed the double walled reactor piping for primary Sodium Coolant in the fast breeder test reactor at Kalpakkam.

A recipient of many honours and awards that includes the ‘FIE Foundation’ medal for excellence in engineering and management from Chief Minister of Maharashtra, he was inducted as a fellow of the exclusive Indian National Academy of Engineering (INAE) in the year 2001. He is active in the academy’s affairs and is a member of its Governing Council. In August 2011, he received the distinguished alumnus award at IIT (Kharagpur) diamond jubilee convocation. He was also awarded the prestigious ‘Vasvik’ award for services to “Structural Engineering and Technology” from PM Narendra Modi (then CM of Gujarat).

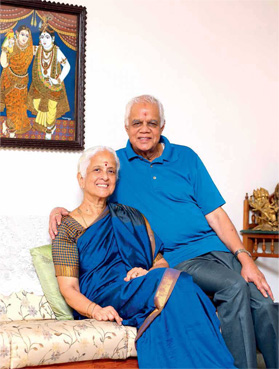

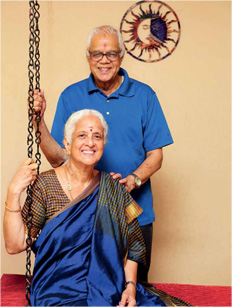

With interests in almost all domains of the ‘good life’, Capt. Mohan Ram is going strong at 80. For him, age is just a number and the glint in his eyes echoes a ‘contented’ disposition to life. He cherishes his family and holds a special camaraderie for his better-half, the much accomplished Vijaya Mohan Ram (former Chief Commissioner of Income Tax, Bangalore). Capt. Mohan Ram shared a slice of their simple yet fulfilled lives with Corporate Citizen.

“After passing out from IIT at the top of the class, I joined the faculty for a year and got a scholarship and teaching admission for doing a PhD. at Cambridge, Massachusetts. But I was much inspired by PM Jawaharlal Nehru at the convocation ceremony at IIT Kharagpur where he exhorted IIT graduates to serve India”

Though I secured admission for engineering courses in Coimbatore, my home town, I opted to go to IIT in distant Kharagpur as I thought Naval Architecture was a new field with a bright future. I did an undergraduate degree in Naval Architecture at IIT Kharagpur (1953-1958). I belonged to the 3rd batch of all IITians. The course dealt with design and construction of merchant ships and not warships. Naval Architecture, by name sounded mellifluous. Other than that, I knew nothing about the discipline! I have always had a penchant for trying new things and venturing into the unknown.

After passing out from IIT at the top of the class, I joined the faculty for a year and got a scholarship and teaching admission for doing a PhD. at Cambridge, Massachusetts. But I was much inspired by PM Jawaharlal Nehru at the convocation ceremony at IIT Kharagpur where he exhorted IIT graduates to serve India. He urged us to build the temples of tomorrow, dams and factories which will ensure India’s future. His words inspired many young IIT graduates to join the forces. Around the same time, the Navy advertised for recruitment to the naval constructor’s corps. I applied and was selected. Against my family’s wishes, I opted to join the Navy, spurning a scholarship at a fine university in the U.S. I majored in design of warships in the U.K. at the Royal Naval College in Greenwich.

After a year at the Royal Naval Engineering College, Plymouth, the next three years were spent at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich. The course was designed primarily for training designers for the Royal Navy. They also admitted students from the Commonwealth and friendly ‘navies’. My classmates comprised Englishmen, a Greek, a Norwegian, a Canadian and another Indian. I topped the international class with a high first class. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy offered to take me in their cadre and promised to defray all expenses to the Indian Navy. The offer was refused by our Navy. In addition to academics, I represented Greenwich College in squash, tennis and hockey. I developed a lifelong interest in western classical music and attended a number of plays at the West End. My stay in the U.K. broadened my outlook and equipped me for my future interactions with people from all over the world. I also became physically very fit, which I maintain till today.

My IIT degree had given me solid grounding in merchant ship design. The U.K. course equipped me with specialised knowledge on warship design and construction. We visited shipyards, industries and research establishments in the U.K. during the course. It was a very high- standard course with Maths that was equivalent to M.A. Tripos in Cambridge. Four years later, I had the unique opportunity of working in the Royal Navy design offices at Bath, U.K., as part of the Indian Leander frigate program. I was the only naval architect to get the opportunity and that totally equipped me for future warship design activity.

Our Navy had no experience of design of ships. I was a member of the group of pioneers who had to struggle against odds. There was no database to work on. India also had no warship construction experience. We were like ‘Sherpas’ climbing the Himalayas without equipment or oxygen. My year at Bath really laid the foundation of ship design in India. I trained a number of youngsters and learnt the knack of getting data on equipment from competing suppliers.

I completed a part-time three year MBA from the Faculty of Management Studies (FMS), Delhi University (1970-73) which is now rated as one of the top non-IIM schools. I belonged to the first batch and topped the course receiving two medals, the Dasgupta Medal (for standing first in the course) and VKRV Rao medal (for topping combined full-time MBA and part-time MBA stream) from G.S Pathak, the then Vice President of India in 1974. There were no electives as such. I took keen interest in accounting, finance and operations management. The MBA did not help me in my naval career at all. In fact, the director in charge of Naval training dismissed my request for tuition assistance, saying that another officer might do a course in wine tasting and ask for assistance! At that time, the top brass in the Navy had no concept of what an MBA was about! The course however came in handy in Mazagon Docks where I got deeply involved in commercial negotiations and quoting for exports due to the expertise I had picked up in Accounting and Finance during my MBA. It was of course, very relevant to my subsequent life in the corporate world.

1959 (August) – S/Lt ; 1961 (February) – Lieutenant; 1963 - topped the course at Greenwich and was commended by the CNS; 1963 - Naval Dockyard, Mumbai into ship repair; 1964-67 in the staff office at the Naval Construction Directorate; 1967-68 – An one year attachment with the Royal Navy design offices in the UK; 1968 - Promoted to Lt. Cdr; 1968-67 - Design of small craft at NHQ and became Commander; in 1970-72 - Directorate of Leander Project on modifications to U.K. design of Indian Giri class frigate; 1974- Attended inter-service course on EDP at Mhow and topped the Course(only first class); 1972-77 - Directorate of Naval Design- Designed small fast patrol craft, landing ship and led the design of INS Godavari; 1977 – was awarded ‘Vishist Seva’ medal by ‘Rashtrapati’ for design of INS Godavari; 1977-79 at Naval Dockyard Bombay, Head of Construction Department in charge of 2500 workmen in ship repair; 1979- Deputed to Mazagon Docks Limited and promoted to Captain and in 1980 - premature retirement on absorption to MDL (Mazagon Dock Limited) service.

Because of my record at Greenwich, I was handpicked for warship design. My year at Bath gave me deep knowledge of all aspects of ship design from sophisticated weapons to humble laundries and galleys (kitchen). I created most of the protocols myself though we had some RN documents which came as a part of the Leander project.

A warship is complex as it floats, moves and fights. It is home to hundreds of sailors and officers and has to provide reasonable comfort to them in a limited space. It moves and therefore has to be maneuverable and survive rough seas. It has to fire weapons and sustain damages and still survive. It has sophisticated wireless communication, cyber warfare and fire control devices. The naval architect therefore has to coordinate and implement all these activities and processes on a single platform. That was my job while planning and constructing the INS Godavari. We discovered that we could use the same power plants as in the earlier ships in the larger ship too. I saved the country thousands of crores of rupees and construction time by implementing this. INS Godavari came about from a realisation among Navy’s planners that shipbuilding was essential to build a strong navy. During 1960 to 1970s, the ‘Leander Frigate Project’ resulted in the construction of six ‘Giri Class’ frigates at the Mazagon Dock and boosted indigenous naval design and shipbuilding capability. The ship’s design was planned during the Cold War.

Design is not just technology. It is a human process of getting groups of specialists to work towards a common objective. It is a commercial process of developing a product to strict cost constraints. The underlying process of design is common to software, hardware and across disciplines. I leveraged my naval experience in Mukand Ltd to design steel plant equipment and in TVS to reorganise design processes in a cross-functional set up. My flair for engineering helped me master varying disciplines. That said, the design of a consumer durable like the ‘Scooty’ posed the additional challenge of understanding customer requirement, market research and market intuition. It was a gradual evolution for me and was immensely enjoyable.

Design is not just technology. It is a human process of getting groups of specialists to work towards a common objective. It is a commercial process of developing a product to strict cost constraints. The underlying process of design is common to software, hardware and across disciplines

No. I first joined the construction industry, then foundry and then steel sectors from 1984 to 1989. My corporate journey began in 1984, when I joined Mukand Limited. In May 1989, Mr. Venu Srinivasan, CMD, TVS Motors Ltd, requested me to join TVS, having heard about my performance in handling labour at Mukand India Ltd. From the Navy to the defence shipyard in MDL, then on to Mukand’s Construction Division, Mukand Foundry and then Mukand Kalwe Steel Plant, my transitions have always been as profit centre head in each of these enterprises. As regards the TVS offer, the job was based in Hosur near Bangalore. My wife who was Commissioner Income Tax, had to move out of Mumbai, and the move suited us. She was posted to Bangalore a few months later and we could be together. That was one major factor in choosing TVS and I joined them in October 1989.

My transition into the corporate world was not easy at all, as I joined in senior positions right away. One issue was that my bosses who were CEOs or Managing Directors were years younger than me. However, I was respectful towards them but made sure they also respected my age and stature

The move to MDL was in an allied job in 1980. At MDL, I expanded my range to cover merchant ships and offshore platforms. I also got terrific commercial exposure which honed my commercial and financial acumen. My first job in Mukand Ltd. in early 1984 as head of the erection division was similar to shipbuilding, in that it involved structural erection, piping and so on. I initially joined the small loss making division of Mukand with a turnover of just Rs.1.5 crore but managed to turn it around and made it profitable. The late Mr Viren Shah, the then CMD of Mukand Ltd. then offered me another sick unit – the Rs.20 crore foundry — to run. Again, I turned it around and made record profits. In 1986, within a span of two years, Mr. Viren Shah and his son Rajesh Shah appointed me as the profit centre head of their Rs.200 crore flagship, Mukand steel plant division. I de-bottlenecked and expanded the plant and doubled its turnover and profits by 1989. I also revamped and expanded the scope of the steel plant.

I then joined TVS Suzuki Limited (now TVS Motor Company Limited) in 1989 which was under the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR). Venu Srinivasan, CMD, TVS Group, invited me to join the company in early 1989 offering the position of President of the then ailing company. I asked for six months to finish my pending commitments with Mukand Ltd., before joining TVS in October.

In 1989, as President of the then ailing TVS Suzuki Limited, I handled labour unrest and violence, declared a 100 day lockout and turned the division to profit in three years. By the time I handed it over in 1996 to my successor, the turnover had more than quintupled, a loss of Rs.five crore became Rs.65 crore PBT(profit before tax). TVS won awards such as the NPC award for productivity, NIQR Quality award and Economic Times/HBSAI award for best shareholder return in corporate India. At a time when the company was struggling to survive, Mr Venu Srinivasan adopted TQC (total quality control) as the mantra for improvement. I protested, “How can you talk of starting an arduous quality journey, when we find it difficult to pay the vendors on time and are making losses?” His reply was, “Mohan, you are wrong; this is the only time when people will listen to the message. They get complacent when things are going well!” With his encouragement and support, I helped to turn around TVS Suzuki Limited within seven years. From 1996 to 2001, I was Director Projects and set up a greenfield plant at Mysore in 15 months at an investment of Rs.170 crore, on time and on budget. Today, after some expansion, the plant produces over a million vehicles a year. From 2001, I have been associated with the company as an advisor, with no operational responsibility. I am a goodwill ambassador for the company! In all the jobs, I had to learn from juniors and face uncertainties. However, hard work, a hope for success, a happy attitude and people-skills helped me. My basic strength as a product designer of national repute also helped me.

Not easy at all, as I joined in senior positions right away. One issue was that my bosses CEO/MD were years younger than me. However, I was respectful towards them but made sure they also respected my age and stature.

I was the pioneer in India in foreseeing the problem of recycling end-of life vehicles. I have been working on it from 2003 and have attended many conferences all over the world and made presentations.

On my urging, the group was formed and I headed it from inception. We formulate the auto industry policy on recycling and interact with government, regulatory authorities and the public. I am also the spokesperson for the industry in this area. I have been invited by the Japanese government METI to join a specialist group and am internationally known in the field.

Make the move as early as possible. I probably left it too late, at age 48 when I transitioned to corporate life. Cdr. Narayanan, who is a senior officer at Infosys left after 15 years’ service foregoing pension. Try to get some management qualification. It will not get you the job but will serve as an added qualification. Target the industry and try to build relevant skill-sets in that particular sector. Get as much detail as you can on the target industry and company and make yourself attractive to your potential employer.

Don’t overemphasised your service experience in your resume. It may be irrelevant to the potential employer. Defence people lack knowledge of finance, costing and accounting. They also have to do a lot more themselves in unstructured situations. Learn from juniors and learn to work under people younger than you. Most importantly, do not overdo talk on defence. It upsets people.

Constantly reinventing one self and looking for challenges. Never accept defeat, as setbacks are steps for progress. Be a winner and enjoy yourself in the job. Quit, if you do not like the job.

Wife of Capt N S Mohan Ram, Vijaya Mohan Ram can lay claim to eminence in her own right – with a distinguished career that culminated in her retiring as the Chief Commissioner of Income Tax, Bangalore. As a working woman, she had her share of dilemmas, juggling and adjustment. But above all what surfaces in their relationship is their mutual admiration and camaraderie

The warm smile that curves into calmness speaks volumes of the journey of a 19-year old young bride who retired as Chief Commissioner of Income Tax, Bangalore. Vijaya is currently on the Board of Directors at GMR Varalakshmi Foundation, the CSR arm of the GMR corporate group. The fruits of her efforts find a quiet reverence in her better half, Capt N.S. Mohan Ram, an accomplished and versatile naval architect and corporate consultant. With equally talented and accomplished children, the charming couple in a tete-a-tete with Corporate Citizen, revealed the ‘unsaid’ mutual camaraderie between the Captain and his soul mate.

“My wife’s career has been more remarkable than mine,” says Capt. N.S Mohan Ram. Their 52 years of marital bliss is much admirable as each traversed their individual professional journeys to come full circle into their common interest in music. “She was just 24 years old with a son and a daughter when she joined the central government service (under UPSC). She has also gone to Princeton for a PG course and to the UK for a course. She has been Comptroller of Capital Issue, a Deputy Director in the Company Law Board, and Director in the Department of Atomic Energy. She finally retired as Chief Commissioner Income Tax in Karnataka. Vijaya has no airs. Nothing. We had parallel careers running, but it did not affect the children’s education,” says Capt. Mohan Ram with much pride in his wife’s achievements.

Capt. Mohan Ram appreciates the sense of detachment and spirituality in Vijaya’s demeanour despite her career stature. “The day she retired, there was a farewell function and people were all in tears but she was not. She was laughing and said enough is enough. People were all singing at the gathering. She is a very good classical singer and when they asked her to sing, she rendered a composition by celebrated singer M.S. Subbulakshmi and a ‘Mira’ bhajan. I saw the tears in people’s eye as she sang and someone said they had felt divinity that day. I was never more proud of my wife than on that day. She was so happy to get out of all that work-life that she has had no regrets. She never even set sight on her department after she retired and just walked away from it; a kind of freedom from the 37 years that she worked. That is something that I cannot do, and admire this in her.”

Vijaya Mohan Ram got married immediately after her graduation in 1964, all at 19 years, a coy bride. “We went through the arranged marriage system. It so happened that my mother’s cousin is the daughter of my father-inlaw’s cousin. This lady suggested my alliance to Mohan’s father as they were looking t for a suitable bride for him. I was 19 years old and Mohan was already 28.” There was an initial reluctance from him as he felt that I was such a young girl and there was a lot of gap in our age. But their horoscopes matched and Capt. Mohan Ram was already serving the Indian Navy in those days.

Vijaya Mohan Ram comes from a very orthodox family. “My father had two criteria for selecting his son-in-law. He always valued a good personality and Mohan was very handsome. The second dictum was on intellectual attainment. Mohan was always a topper at college and I too was good in studies. So my father’s thinking was that he should get someone with intellectual compatibility for a perfect alliance. In our community, people do not normally marry off their daughters to somebody in the armed services. But my father said that the boy is very handsome and accomplished, and so I did not bother about other things. Today we are into our 52nd year of matrimony.”

One thing that Vijaya cherishes in Capt. Mohan Ram is his intellectual curiosity. “He is so much interested in learning and knowing so many things. I admire his intelligence, his versatility and his intellectual curiosity. He is versatile in every aspect – in classical music it is any genre -- Hindustani, Western or even Carnatic classical music. Though I sing, he is more knowledgeable than me on that subject. Similarly, on any topic – say, when our son who has a PhD in business economics was preparing a paper with his colleague, Mohan Ram was able to contribute to that too. Even our grandchildren communicate with him as he is very good in everything– a multifaceted personality!”

Vijaya did not have a career immediately after her marriage to Capt. Mohan Ram. “Because Mohan is a naval constructor, he never went to sea and was not the typical sort of naval officer. We never had a typical naval life because he was always on shore. Post-marriage he was posted to the naval headquarters and it was as good as any person working in an office. Even when we went to Delhi we never stayed in the services enclave and lived in flats outside. I have never been to a naval party. My husband and I are very much interested in music and he did not want me to work precisely for this reason in the early days.” He admired her vocal capabilities and had commented, “you have such a lovely voice, music will be your causality if you work.’’ “It was indeed difficult to pursue music. I though try to sing for half an hour every day,” she said.

Vijaya and Capt. Mohan relocated to Delhi in 1964 and then she went to Chennai for the birth of their daughter in 1965. She was a housewife until then. In March 1966, when Capt. Mohan Ram set sail for his training at the Royal Navy College in Bath U.K., she mulled over the idea of pursuing a career. Since the family was not allowed to join Capt. Mohan Ram in the U.K., she had no option but to go back to Chennai, from where she appeared for the competitive exam.

“However, I was reluctant to appear for the Civil Services as I had not prepared for the exams at all. But my father reasoned that I was left with only three chances then, having relinquished the previous year. He said, “Although you have not prepared, do write the exam, as in these exams there is no absolute pass and fail. They select the top 100 or 150 meritorious students and even if you don’t get it, you will get a feel of the exam.”

She did write the exam but was not at all confident of passing them. She reminisces, “I still remember the day of the result. I had come from my mother-in-law’s house to my father’s house. Appa was getting ready to go to office... At the time, my cousin too rang up and asked for my roll number and said that the results were out. We checked the results in the newspaper and I just could not believe my eyes that I had got through the written exam and now had to appear for the interview. By the time I had finished my interview, Mohan was back from the U.K. When we got my results, sometime towards the end of May-June 1968, I went back to Delhi with my daughter.”

Balancing home and work was uppermost in Vijaya’s mind and keeping this in sync, she did not opt for the IAS. She says, “My first choice was Audits and Accounts because my father was with the AGS (Accountant General) office; my second choice was Income Tax (IT). I did not get Audits and Accounts, but I got IT and that’s how I got into the services.”

As with any other working woman at the threshold of her career, but also wedded to the armed forces, Vijaya Mohan had to endure and take some bold steps.

Post induction into the services, for the first four months, Vijaya had to go to Mussoorie to undergo the Foundation Course at the Lal Bahadur Shastri Academy (erstwhile National Academy of Administrative Services), as do all IAS and other services officers. But she soon realised that she was expecting her second child and wondered what to do about this situation.

“The dilemma also came as to what to do with my daughter. I had brought her up personally and never had separated from her.” But, then she did go for the training in 1968, leaving her daughter with her mother in Chennai. “After the initial period at Mussoorie, I had to go to Nagpur. Although, my daughter was well settled with my mother, Capt. Mohan Ram believed that I should not be separated from our daughter.” Stoic Vijaya Mohan then decided to rent accommodation in Nagpur and started rebuilding herself in the second phase of her training regime by weaving her life single handedly at the Nagpur training institute with her daughter. “That was the toughest time, as transportation was via cycle rickshaws, no phone or landlines. There were no gas cylinders so I was cooking on a kerosene stove. Come to think of it, that period in 1968-69, was one of the toughest times of my life.”

Post-Nagpur, she once again joined her husband in Delhi and their son was born in March 1969, but she had to forgo her departmental exams as she was on maternity leave. This was when she once again called upon her mother, who stayed with her for eight months to take care of Vijaya and Mohan’s kids, as Vijaya gradually stepped up on her career path. “So, once again, I took a six-week old child and my two-year old daughter to Nagpur to complete the second part of the unfinished training from May to November 1969.”

“He is very interested in learning and knowing so many things. I admire his intelligence, his versatility and his intellectual curiosity. He is versatile in every aspect—in classical music it is any genre—Hindustani, Western or even Carnatic classical music. Though I sing, he is more knowledgeable than me on that subject”

After completing her training, she was posted in Delhi as per an informal rule “that husband and wives should be posted together.”

In December 1976, Capt. Mohan was transferred to Mumbai and she got hers in June 1977. From September 1977 to 1978, she went to Princeton University and Mohan looked after the kids. This was under the aegis of the prestigious Parvin Fellowship. “My career would not have been good if it was not for my husband’s cooperation. My son was eight years old and daughter 12. I studied at the Woodrow Wilson Public school for a year, which was more on public administration. I was then, undersecretary in the Economic Affairs department (Deputy Commission in IT)”.

After her Princeton programme, she was posted in Mumbai as Additional Commissioner of Income Tax. “In the department itself, I had various postings. Eventually, I was empanelled for the Director’s post from the central government and then went as Director, Dept. of Atomic Energy during 1986 to 1989 in Mumbai.”

Vijaya says her children studied by themselves. “However, my husband contributed a lot to their studies in grades 10th and 12th. He was in the Navy so would take leave during the kids’ exams. Before he joined the private sector in 1984, I remember my son was in grade 10th and Mohan took a month’s leave after he had left Mazagaon Docks Ltd. He sat at home and guided my son in his Xth grade. For his IIT and further studies, my son did it all on his own. My daughter also joined TISS and worked for HP.”

“In my opinion, working women, because they feel a lot more guilt, feel the need to compensate more for the lost hours that they are in office. I would say working women with kids should have their priorities very clear. You ought to take it a little easy on your ego. If you stand on your ego too much, you hurt yourself and your children. It is a question of adjustment..”

By Sangeeta ghoSh DaStiDar