In Bhutan, the concept of Gross National Happiness (GNP) has greatly enabled the pursuit of development, while at the same time promoting the attainment of happiness as the core philosophy of life. For the government, it has facilitated the drive towards self-sufficiency and self-reliance, the ultimate reduction in the gap between the rich and the poor and ensuring good governance and empowerment of her people as one of its key directives

With his famous declaration in the 1970s, the former King of Bhutan challenged conventional, narrow and materialistic notions of human progress. He realised and declared that the existing development paradigm— Gross Net Product (GNP) or Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—did not consider the ultimate goal of every human being: happiness.

Perhaps inspired by age-old wisdom in the ancient Kingdom of Bhutan, the fourth King concluded that GDP was neither an equitable nor a meaningful measurement for human happiness, nor should it be the primary focus for governance; and thus the philosophy of Gross National Happiness: GNH is born.

Since that time this pioneering vision of GNH has guided Bhutan’s development and policy formation. Unique among the community of nations, it is a balanced ‘middle path’ in which equitable socio-economic development is integrated with environmental conservation, cultural promotion and good governance.

For over two decades as Bhutan remained largely isolated from the world, GNH remained largely an intuitive insight and guiding light. It reminded the government and people alike that material progress was not the only, and not even, the most important contributor to well-being. As Bhutan increasingly engaged with the global community, joining international organisations, substantial efforts were made to define, explain and even measure GNH. Indices were created, measurements were recorded and screening tools for government policy were created, and the second phase in the development of GNH saw its practical implementation in government become a living reality.

The folly of an obsession with GDP, as a measure of economic activity which does not distinguish between those activities that increase a nation’s wealth and those that deplete its natural resources or result in poor health or widening social inequalities is so clearly evident. If the forests of Bhutan were logged for profit, GDP would increase; if Bhutanese citizens picked up modern living habits adversely affecting their health, investments in health care systems would be made and GDP would increase; and if environmental considerations were not taken into account during growth and development, investments to deal with landslides, road damages and flooding would be needed, and GDP would increase. All of these actions could negatively affect the lives of the Bhutanese people yet paradoxically would contribute to an increase in GDP.

“How are you?” We ask that question of one another often. But how are you doing - as a country, a society? To answer that question, Bhutan uses its Gross National Happiness (GNH) Index. The GNH Index this year is 0.756, improving on the 2010 value of 0.743.

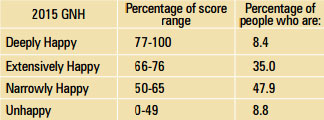

In 2015, a total of 91.2% of Bhutanese were narrowly, extensively, or deeply happy. 43.4% were extensively or deeply happy. The aim is for all Bhutanese to be extensively or deeply happy. Bhutan is closer to achieving that aim in 2015 than it was in 2010.

GNH is a much richer objective than GDP or economic growth. In GNH, material well-being is important but it is also important to enjoy sufficient well-being in things like community, culture, governance, knowledge and wisdom, health, spirituality and psychological welfare, a balanced use of time, and harmony with the environment.

The 2015 GNH Index on a purpose-built survey of 7153 Bhutanese in every Dzongkhag of Bhutan. From that, analysts create a GNH profile for each person, showing their well being across in the nine domains mentioned above. The national GNH Index draws on every person’s portrait to give the national measure. 91.2 percent of Bhutanese are narrowly, extensively, or deeply happy.

The 43.4 percent of Bhutanese are extensively or deeply happy, up from 40.9 percent in 2010. Across groups:

Across districts, GNH was highest in Gasa, Bumthang, Thimphu, and Paro, and lowest in Dagana, Mongar, Tashi Yangtse, and Trongsa.

GNH increased significantly from 2010-2015 by 1.8 percent.

The GNH index findings paint an intricate and textured picture of the lives of Bhutanese, tracing them with much greater care and curiosity than GDP or any other existing index. Dasho Karma Ura, Director of the Centre for Bhutan Studies and GNH Research, said: “The 2015 GNH Index provides a self-portrait of a society in flux, and offers Bhutanese the opportunity to reflect on the directions society is moving, and make wise and determined adjustments.”

The four main pillars of GNH are:

These pillars embody national and local values, aesthetics, and spiritual traditions. The concept of GNH is now being taken up the United Nations and by various other countries.

Crucial to a better understanding of GNH, is its wider reach and awareness amongst other countries, and the various indices that have now been formulated to include material gains in their assessment of the country and lastly, the growing need to synthesise the moral with the cultural values as the core of economic policy.

GNH as a development paradigm has now made it possible for Bhutan to take its developmental policies into the remote corners of the kingdom and to meet the development needs of even its most isolated villagers, while still accentuating the need to protect and preserve our rich environment and forest cover. The policy of high value, low impact tourism has facilitated the promotion and preservation of our cultural values.

Furthermore, the concept of Gross National Happiness has greatly enabled the pursuit of development, while at the same time promoting the attainment of happiness as the core philosophy of life.

For the government, it has facilitated the drive towards self-sufficiency and self-reliance, the ultimate reduction in the gap between the rich and the poor and ensuring good governance and empowerment of her people as one of its key directives.

By Vinita Deshmukh