From Fighter Jets to Civilian Clouds

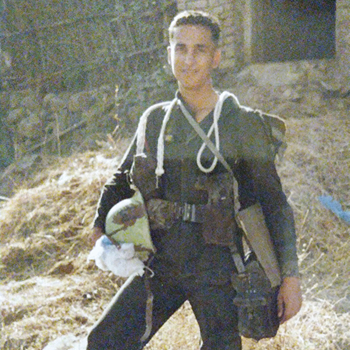

From watching Republic Day parades with his father in Delhi to soaring the skies as a fighter pilot, Wing Commander Amit Sathe (Retd) has carved an extraordinary path as a first-generation Armed Forces officer. He has had the rare distinction of shifting from the Helicopter to Fighter stream in the Indian Air Force—one of the very few to achieve this feat. Over a 20-year career, he flew 12 different aircraft types, served as an Advanced Jet Trainer for rookie fighter pilots, was part of the elite Surya Kiran aerobatic display team, and has earned a Master’s degree in Defence and Strategic Studies from the prestigious Defence Services Staff College, Wellington, Tamil Nadu. After voluntary retirement, he now flies Boeing 737s for Air India Express

Corporate Citizen: You’re a first-generation Armed Forces' officer in your family. Was it always a childhood dream?

Wing Commander Amit Sathe (Retd): There was no one in the government service in my family, let alone in the Armed Forces. My father had a strong desire to join services, but he did not clear at the first attempt, and was dissuaded by his parents to give another attempt. However, his interest never faded.

Growing up in Delhi, we never missed the Republic Day Parade, where my father would explain every regiment to me, especially highlighting paratroopers and fighter pilots as the elite, the best of the best. That left a lasting impression. I began to see the Armed Forces as a ladder—first, become a fauji and then, if you're truly exceptional, you make it to one of these elite units. What sealed the deal for me, though, was a visit to the Air Force Museum at Palam in Delhi. That’s when I knew I wanted to be a fighter pilot.

CC: Dreaming is one thing, but how was your experience at the National Defence Academy (NDA), where you joined as a cadet?

Qualifying for the NDA itself was a big milestone for me and my family. It begins with the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) examination, followed by a rigorous five-day Services Selection Board (SSB) interview. Most people aren’t aware that it’s the only interview in the country that lasts for five continuous days. You stay at the centre and your personality is evaluated using three different psychological techniques. They look for specific officer-like qualities that the Armed Forces believe are essential for leadership and military service.

Clearing the SSB is followed by an intense medical examination, even more stringent for the Air Force than for the Army or Navy. Once you’ve cleared all this, a final merit list is drawn up. But, in my case there was still one more hurdle—the Pilot Aptitude Battery Test (PABT), which is a one-time test. You only get one chance in your life to clear it. If you fail, you're permanently ineligible for flying in any wing — Army Aviation, Naval Aviation or the Air Force. Fortunately, I cleared it.

All the stages from the written exam, SSB, medicals and the PABT, built my confidence immensely. It was a proud moment when I received the call letter to join NDA as an Air Force cadet. The initial roll numbers ran into lakhs, but finally, only about 60 cadets were selected for the Air Force in my batch. It’s so competitive that even some who make it to the overall merit list don’t get into the Air Force due to limited seats; they’re then allotted their second or third preference.

So yes, receiving that letter felt like a dream come true. Once I entered the Academy though, I quickly realised that the entrance exams and selection process were just the beginning. The real challenge began at the NDA, where mental, physical and emotional transformation truly started.

"What truly drew me in, though, was the sheer independence and responsibility that comes with being a fighter pilot"

-Wg Cdr Amit Sathe (Retd)

CC: What’s the academic curriculum like at NDA?

The curriculum at NDA is extremely rigorous and unique. In fact, NDA is the only academy in the world where cadets of all three services — the Army, Navy and Air Force, train together before graduating. NDA also awards a graduate degree upon completion. During my time, I earned a Bachelor of Science (B.Sc) degree from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

Today, the academic programme has been significantly upgraded. Cadets now receive a B.Tech degree, especially those in the Air Force and Navy. For the Army, there’s still a choice between pursuing a BA, B.Sc or B.Tech, but for the Air Force and Navy, engineering is now compulsory.

The curriculum is multifaceted. Along with core academic subjects, cadets are also introduced to foreign languages, providing them exposure to global cultures and communication, which are important skills in international military cooperation. It’s a challenging environment, balancing academics with intense physical and military training, but it’s precisely this rigour that shapes cadets into well-rounded officers.

CC: Please elaborate on the comprehensive training at the NDA.

At the NDA, physical training is an integral and demanding part of cadet life. While certain activities have minimum mandatory requirements, cadets are encouraged to push themselves further and aim for higher levels, often voluntarily. For instance, in foreign languages, you receive basic exposure, but you also have the option to appear for certification- level examinations.

The physical training includes standard physical exercises, daily PT sessions and foundational gymnastics. Horse riding is part of the curriculum as well, a skill that builds balance, confidence and discipline. You also study cross-disciplinary subjects such as military history, geography and economics. These are non-credit courses, which you must pass, but they do contribute to your final grade. The credit courses on the other hand, are graded on a nine-point scale and contribute to your cumulative grade point average, which ultimately determines your degree classification upon graduation.

It’s a highly multifaceted and intense academic and training environment. A particularly memorable component of NDA life is the series of military camps—it’d be remiss not to mention them—which are in a sense, the highlight of our physical endurance training, like the cherry-on-the-cake. There are three main camps during the six-term (three-year) programme, in the 2nd, 4th and 6th terms.

The first camp, in the second term, is called Camp Greenhorn — a symbolic name drawn from the green horn of a young rhinoceros, indicating the cadets’ early stage in training. The fourth-term camp is Camp Rover, widely regarded as the toughest of the three. At around 19 years of age, cadets are tested to their physical and mental limits in this phase. The final camp, in the sixth term, is called Camp Torna or Trishul, reflecting the tri-services nature of NDA. It serves as a transition into service-specific training.

For the first four terms, all cadets undergo common military training — basic weapon handling, tactical exercises and general service protocols. In the final term, the training becomes specialised based on the cadet’s service — Air Force, Army or Navy. This term prepares cadets for their respective service academies post-NDA: the Indian Military Academy (IMA) for Army cadets, the Indian Naval Academy at Ezhimala for the Navy, and the Air Force Academy in Dundigal, Hyderabad, for the Air Force.

CC: So, why did you choose the Air Wing?

My decision to join the Air Wing traces back to childhood memories and influences. As a boy, I was captivated by stories of aerial battles, both from what my father shared and from reading Commando comics, which vividly portrayed air warfare. If I hadn’t become a fighter pilot, I’m certain I would have opted to be a paratrooper. So, it was really a close call between the two elite streams.

On a lighter note, I must admit the film Top Gun, which released in 1986, had its impact. It glorified and romanticised the life of a fighter pilot with fast jets, daring manoeuvres, and high-adrenaline drama. Of course, once I actually joined the Air Force, I realised real-life flying, bore little resemblance to the cinematic portrayal. There are no motorbikes racing down airstrips or dramatic slow-motion stunts, but the seed of fascination had already been planted.

What truly drew me in though, was the sheer independence and responsibility that comes with being a fighter pilot. In most military roles whether commanding a ship, a tank, or an engineering unit,you lead a team. You're the officer guiding a group. However, in a fighter aircraft you are alone in the cockpit. Yes, you operate as part of a networked air formation, but in that moment, inside that machine, you are the sole master.

I often used to draw comparisons for my naval counterparts—your ship has guns, we have guns. You have missiles, we have missiles. Navigation systems, electronic warfare, radar—everything that you have on a ship, we have in an aircraft. While a ship has separate officers managing each of these systems, in a fighter jet there is only one person doing it all. The pilot must understand every system, every response, every failure protocol, immediately and instinctively.

"When a fighter pilot goes down in a crash, especially a fatal one, we often say it wasn’t just the aircraft that was lost. That pilot used the sum total of his training, instincts and judgement, to make a final decision. When that decision fails, all of us who trained and flew with him lose a part of ourselves too"

CC: What does it mean to be a successful fighter pilot?

In a fighter jet you're not only the pilot, you’re the systems operator, engineer, weapons controller and navigator. You must even have a basic understanding of aviation medicine. There’s no on-board doctor, so you need to know how your body will respond to G-forces, what medication might impair judgement, how to recognise hypoxia or spatial disorientation and deal with it. In that sense, the closest civilian profession I can compare it to is not even a general physician, but a surgeon. Someone who must make precise, critical decisions under pressure, with no room for error.

That’s why, when a fighter pilot goes down in a crash, especially a fatal one, we often say it wasn’t just the aircraft that was lost. That pilot used the sum total of his training, instincts and judgement, to make a final decision. When that decision fails, all of us who trained and flew with him lose a part of ourselves too.

Fighter aircraft are at the pinnacle of human technological achievement. These aren’t just machines—they’re national assets. So, when you put a person inside such a platform, it requires rigorous checks, thorough preparation, and absolute confidence that only the best-trained individuals are entrusted with them. And that’s what it means to be a fighter pilot.

CC: You’ve flown a variety of aircraft in the Air Force. Tell us more about that.

Interestingly, I never chose my stream, it was more a matter of destiny. Like many young officers, I was passionate about becoming a fighter pilot. However, in the Air Force, the allocation to Fighters, Transport or Helicopter streams, is based on merit and institutional requirement. Despite securing a good merit, I was assigned to helicopters.

Naturally, I was disappointed. While one doesn’t question decisions in the Armed Forces, I did make a representation, expressing my strong desire to join Fighters. The response was clear: “We need the best pilots in helicopters too, and you've been trained at the nation’s expense. Now it’s your duty.”

So, I accepted it and began my career in helicopters. Just then, Operation Parakram was launched following the Parliament attack in December 2001. We were commissioned on 15th December 2001, and within five months, by mid-2002, the situation had escalated. Our training was cut short, and I was deployed to the frontlines. I had the honour of flying operational missions and was awarded the Operation Parakram medal.

Despite being deeply committed to the role, my heart still yearned for Fighters. I continued to represent my case while giving my best in helicopters. I flew the Chetak and Cheetah (light utility helicopters still used by the Army and Air Force), both originally French, but now built in India. I was then upgraded to the Russian-made Mi-8 which is the older cousin of Mi-17 and is still in use.

Recognising my persistence and professional performance, I was selected at a relatively young age for the attack helicopter stream. I trained on the formidable Mi-25/35, which was featured famously in the English movie, Rambo III. These are heavily armed assault helicopters, closer in operational spirit to fighter flying.

Eventually, after numerous representations, I got an opportunity to speak directly with the head of the Air Officer Personnel. I was finally referred to the Air Force chief himself—that conversation marked a turning point.

"If your government and fellow citizens place their trust in you, that is the highest privilege. This profession calls for rising above personal interests and greed, to serve something greater than yourself"

CC: Tell us more about your persistence.

As a Flying Officer, I had the rarest of opportunities to meet the Chief of Air Staff himself. It’s almost unheard of at that level, and I had worked tirelessly to make it happen. I conveyed my unwavering desire to fly Fighters, and he was gracious enough to consider my request.

There was understandable hesitation as there were no precedents for such a cross-stream transition. The concern was that allowing one case might open the floodgates. I respectfully argued that moving from Helicopters to Fighters wasn’t a shortcut, it was in fact, a leap into something more demanding. I had already mastered a different flying discipline and was now asking to start afresh in the toughest stream.

The Air Force Academy put me through a month-long evaluation to assess my potential, and I received an above average to exceptional grading. Based on this, the bold and momentous decision was taken—I was cleared to shift to Fighters.

In the long history of the Indian Air Force, only a handful have ever transitioned streams, and fewer still have succeeded. I was proud to be among them.

I rejoined a course with cadets who were three years junior to me, and I’d never trained with before. Any sense of seniority had to be set aside. I became a student again, working hard to catch up. For them it was their first aircraft, for me it was a second beginning.

CC: Tell us about your progression to fighter jets and which ones you flew.

In the armed forces, your career follows a structured progression—certain qualifications and courses must be completed within specific timeframes. Since I switched to Fighters midway, I was already behind schedule, which put me at a career disadvantage. I pressed on—trained on the MiG-21 and qualified, just about within the permitted number of attempts for my service year. My competition wasn’t the peers I was flying with, but those from my original course. Still, I pulled it off and was selected as a Fighter Instructor.

I was then posted to fly the Hawk aircraft as Advanced Jet Trainer (AJT). Later, when I was given the option of returning to my old fleet MiG-21 or the Sukhoi Su-30MKI, I opted for the latter as it was the best platform available at that time. Although, most pilots joined the Sukhoi stream within two to three years of service, I entered it much later, as a Wing Commander with over 12 years in uniform.

Despite the delay, I earned all required operational qualifications in a record time of three to four years. Eventually, my career path led me to Staff College—a non-flying role where I completed my post-graduation in Defence and Strategic Studies.

After completing my M.Sc in Defence and Strategic Studies, I returned as an instructor on the Hawk aircraft for a second tenure.Within two years, I was appointed as a Flight Commander.

Following that, I had the privilege of joining the Indian Air Force’s aerobatic display team, Surya Kiran. Over the course of my career, I flew around 12 different types of aircraft—a significant number, considering most pilots typically fly between four to six. Anything beyond seven is considered exceptional.

I suppose, my professional journey has always leaned towards embracing challenges and calculated risk. With that mindset and believing that one only lives once, I chose to step out of service after completing over 20 years of commissioned service in the Indian Air Force.

CC: When did you take your voluntary retirement?

I took premature retirement in 2022. I was commissioned in December 2001, so I served for just over 20 years and four months. I left the Air Force on 30 April, 2022.

CC: What is your experience of working as a commercial pilot?

Becoming a commercial pilot was like starting from scratch. Each new aircraft you to completely reset your mindset commercial aviation, while safety top priority, commercial also the key, you have to think differently.

Now, you’re carrying passengers who place complete trust in you. When people board a flight, they don’t question the pilot’s competence; they assume the best. That trust places a huge responsibility on your shoulders.

As a pilot, you must make calm and balanced decisions, guided by common sense and an unwavering focus on safety, all the while meeting commercial objectives. My flying experience from the Air Force has been immensely valuable, as it continues to guide me every day in civil aviation.

If I have to say it, you're driving a Formula One. Now, I have come to driving a bus. Now I'm trying to stick to those same ethos over here, wherein whatever job has been assigned to me, I try to do it.

"As a commercial pilot, you are carrying passengers who place complete trust in you. When people board a flight, they don’t question the pilot’s competence; they assume the best. That trust places a huge responsibility on your shoulders"

CC: Let’s talk about the recent Operation Sindoor. From an Air Force perspective, especially as a fighter pilot, how do you view it?

Operation Sindoor was quite unique compared to previous conflicts. Traditionally, air power involved crossing borders and sustained attrition warfare, like in Kargil. Here, all action took place within our own territory with no crossing of the Line of Control. It was swift, precise, and contained within minutes rather than weeks.

In mountainous warfare, the attacker needs overwhelming numerical superiority—often 10 or 11 fighters to one, to succeed. In the plains, it’s about five or six fighters to one. Operation Sindoor was different; it was a rapid, high-precision strike with no prolonged ground engagement.

This was the first time since the Gulf War that we saw such air power demonstrated live on television. Precision strikes targeted terror camps exclusively, sparing civilian infrastructure. Intelligence was spot-on, enabling shock, speed and precision—classic air power textbook execution.

It was a turning point, showing that major strategic effects can be achieved without boots on the ground.

CC: What message would you give to youngsters aspiring to join the Indian Air Force?

The profession of Armed Forces is noble and timeless. If your government and fellow citizens place their trust in you, that is the highest privilege. When your military leads, you need to lead from the front, as we saw in the recent conflict. This profession calls for rising above personal interests and greed, to serve something greater than yourself.

Think of the respect doctors earned during the Covid pandemic when risking their lives; soldiers hold a similar exalted place because they protect us all. Joining the Air Force offers honesty, minimal interference, and a unique camaraderie that is truly extraordinary. It’s a path worth considering.

CC: What is the philosophy of life that you live by?

The NDA taught me this most importantly: "It is 'your' responsibility to be happy and content—no one else’s. Define your duty, purpose and goals clearly. Pursue them diligently without obsessing over results" .

For example, I dreamed of being a fighter pilot but started as a helicopter pilot—I gave my best regardless. Focus on doing your best and find contentment within yourself. Happiness is a personal responsibility, no external factor can grant it for you.