Media on the Firing Line !

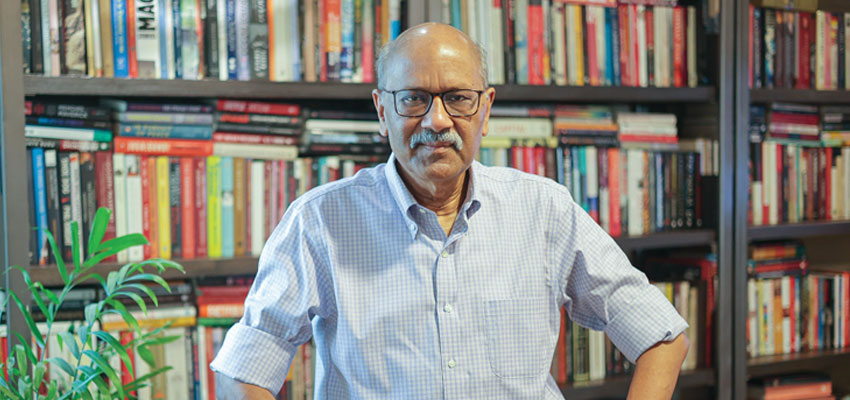

Shekhar Gupta is an award-winning journalist, columnist, author and talk show host. In 2017, he became the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of ThePrint, India’s fastest growing new media platform known for its non-hyphenated journalism.

His highly influential weekly column National Interest is translated into five languages. A selection of these columns was collected in the bestselling book Anticipating India.

In his nearly five-decade career, Shekhar has reported on key events, including trouble in India’s Northeast, Operation Blue Star, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the first Gulf War from Baghdad, Sri Lanka's troubled decade of 1983-1993, and has done more than a dozen tours of duty in Pakistan.

Here, he speaks exclusively to Corporate Citizen on the radically changed face of the print, online and television media, over the last 10 years. Read on for an insightful analysis

Corporate Citizen: What was the turning point for the media, leading it to focus more on news features and opinion-driven content?

I think the major turning point we’ve seen was15 years back, when the Anna movement coincided with the UPAII government, party becoming weak. It was damaged from inside by the Congress party itself. Because many suddenly took a dislike to Manmohan Singh and they thought policies were too pro market.

As the UPA lost ground, the Anna movement gained momentum, reflecting a growing public perception of government corruption. At the same time, social media was emerging as a powerful influence, particularly with the arrival of Twitter in India around 2007-2008. People quickly adopted it. So the Anna movement was a blend of social media influence, and a media environment where TV channels saw TRPs rise by supporting this cause. This marked the point where news media began transforming into "views media".

CC: So, the era of 'Views Media’ began?

With this shift, media outlets felt compelled to take a position, often aligning with the prevailing narrative. Ultimately, the BJP capitalised on this shift, and we saw Anna Hazare's role dwindle, while the media continued down this opinion-driven path. When the BJP came to power with a strong majority and Mr. Modi’s popularity surged, the social media environment polarised further. To go viral, one had to be either strongly pro-Modi or anti-Modi, with little regard for factual accuracy.

Similarly, the TV media became overtly pro-Modi, leading to a rise in anti-Muslim sentiment and hyper-nationalism. Following events like the Uri attacks in 2016 and 2019, we saw the media embrace a militaristic, hyper-nationalistic stance, with retired veterans on TV channels expressing their strong opinions.

Now, in response, we see a new wave of YouTubers taking strong stances to build audiences, often disregarding facts. This creates challenges for the traditional media, which aims to listen to both sides and draw balanced conclusions. It is now increasingly outpaced by opinion-driven content.

"Public-interest journalism has taken a backseat. Previously, citizen voices—including retired armed forces personnel—were proactive in fighting for city issues"

CC: Besides the BJP cashing on the opportunity, do you think the Anna movement spurred TV channels or newsprint to continue to genuinely taking up citizens' issues?

I don’t think any TV channel has undertaken a truly substantive investigation—like an in-depth, multi-part series exploring, for instance, why Bengaluru gets flooded every year. The answer is clear - lakes and watercourses are covered over with buildings, and without thoughtful planning, water has nowhere to go on the plateau, leading to recurrent flooding

Yet, no channel has delved deeply into this. And it’s not necessarily a matter of motive; I just believe TV channels no longer employ journalists with the skills or resources for that level of investigative work. Even if they cover a flood story, it's typically brief, lacking depth. Besides, such stories aren’t likely to attract sponsorship, and if they aren’t sponsored, they won’t make it to air.

In today’s environment, if a channel did have journalists with that expertise, they’d be left underutilised much of the time. Increasingly, TV journalism is about events and summits, where the objective is to secure big names, like the Prime Minister or Finance Minister. This shift has severely distorted the media landscape.

CC: Do you think this shift has harmed genuine public-interest journalism, and that citizen voices, such as retired armed forces members once active in city issues, are now less engaged?

Absolutely. Public-interest journalism has taken a backseat. Previously, citizen voices—including retired armed forces personnel—were proactive in fighting for city issues. But today, with media prioritising sponsorship and high-profile events over genuine issues, that commitment to public causes has waned significantly. People are no longer rallying behind city or civic issues the way they once did.

CC: Do you think that public journalism is dead?

No, it’s not dead—nothing truly dies. But public journalism has declined because mainstream media no longer sees value in it. Take Pune, for instance, THe Indian Express pioneered civic journalism with its Resident Editor Prakash Kardaley, leading it. Pune was an ideal place for this type of journalism because people here feel a strong loyalty to their city. Unlike other cities with many "parachute" residents who come and go, Pune has a core of long-term residents, including retirees, who see the city as their permanent home.

In contrast, mainstream media finds it commercially challenging to sustain civic journalism. Sponsors are rare, and the content typically doesn’t attract the massive viewership needed for substantial advertising revenue. That’s why The Indian Express pursued it in Pune, while other major newspapers like THe Times of India, didn’t.

CC: Do NGOs fill the gap left by mainstream media in public journalism?

Some NGOs have tried, but many lose focus, shifting from one cause to another—anti-corruption one day, then religious issues or civic quality the next. There’s an overall lack of a sustained civic movement in India. For example, recently we reported that the government allocated Rs. 3,900 crore to Bihar for sewage treatment plants to clean the Ganga, but only seven plants have been completed. Yet this will probably not cause a public outcry in Bihar about why the Ganga remains polluted.

CC: What inspired you to leave established editorial roles at major national dailies and magazines and take on something new?

I wanted to shake things up a bit. Life had become too comfortable, and I felt it was time for something more adventurous. In my parting message to The Indian Express, I mentioned wanting to step out of my comfort zone—I was 57 then and realised I could keep going as I was, for a few more years, but would essentially be doing the same thing. So, I thought, why not try something different?

CC: What areas do you focus on in your current role?

The main focus is on politics, governance, society, and culture. I wish we could cover more sports, but we can only handle so much at once. It’s a bit of a regret since sports coverage could be valuable. Maybe then we’d understand why India was 44 for nine on a particular day. But overall, civic issues, governance, and the societal pulse are our mainstays.

CC: Do you think young people today show apathy toward civic issues or even sports?

Yes, apathy is evident, not just toward civic issues but in areas like sports as well. For example, when India was playing with Germany in an Olympic hockey semi-final, no screen in the office was showing it. This reflects a broader disinterest in things beyond the immediate, which is part of the challenge with civic engagement today.

CC: How would you describe the temperament of young journalists today compared to your early years?

Young journalists are largely the same—they’re ambitious, impatient, and impetuous. They often dislike their editors because editors teach patience, realism, and the importance of grounding their work rather than chasing immediate fame. This dynamic hasn’t changed much over time.

CC: Has there been a shift in how editors approach their roles?

Absolutely. Many editors are now treated more like managers, a shift that Times of India introduced about 30-35 years ago, merging editorial roles with managerial titles. For example, an editor might also be labelled as a senior vice president, blurring the lines between editorial and management. In my days, there was a strict separation between editorial and managerial functions—a "Chinese wall", as we called it. I experienced this first-hand, even when serving as both editorial chief and CEO, at The Indian Express, ensuring that editorial integrity remained intact.

CC: What challenges do today’s editors face, particularly from corporates, celebrities and politicians?

One significant challenge is managing access. Politicians, celebrities, and corporate figures have all learned to wield access as a form of control. If they dislike how they’re portrayed, they cut off access, making it tough for reporters to gather information or secure interviews. Editors face this challenge when trying to secure high-profile guests for events, which have become important revenue sources for media organisations. This reliance on VIP access complicates editorial independence and adds a new layer of complexity to the editor’s role.

And definitely not any journalist today who's reporting or who's writing has any experience before this, of working under a majority government. Because the last majority government fizzled out in 1989 and that too in its last two years it was a lame duck government. After Bofors happened, 1987 onwards, it was a weak government.

CC: What are your thoughts on the Right to Information (RTI) as an investigative tool in journalism? Has it strengthened journalism?

RTI has definitely strengthened journalism, but not as much as it could. There are a few reasons for this. Firstly, while the government initially granted RTI, they were never fully supportive of it. Even previous governments would often block information where they could. The current government has taken this further, and RTI now functions as a shadow of what it was meant to be.

CC: Are there challenges journalists face when using RTI effectively?

Yes, one of the biggest challenges is developing the skills to effectively use RTI. There are only a few journalists, like Shyamlal Yadav from The Indian Express and of course you (Vinita Deshmukh), who really know how to use RTI well. Utilising RTI requires patience and perseverance because once you file a request, you may have to wait for a response, potentially file an appeal if denied, and sometimes go through multiple rounds. To do this, news organisations need the resources to assign someone full-time to RTI requests, without the pressure of producing a story every day.

CC: How do corporate interests use RTI, compared to journalists?

Interestingly, corporate lobbyists and other interest groups often use RTI more skillfully than journalists. They may employ RTI to obtain information to undercut a rival’s project or agenda, whereas journalists don’t always have the same strategic approach. It’s a mixed outcome—RTI has great potential, but more journalists need to develop the patience and skills to make full use of it.

CC: Looking at online readership, do you think there is a particular age demographic, like those over or under 40, that finds online journalism more credible?

Yes, online journalism is gaining credibility across age groups. However, a lot of online journalism still tends to be polarising, leaning heavily to one side or the other.

CC: How does this polarisation impact journalism that tries to remain factual and centred?

The challenge is that much of the online space is dominated by polarised perspectives, leaving less room for journalism that strives to be in the centre. By "centred," I don’t mean neutral, as no one is entirely neutral. Instead, it means forming positions based on facts and the specifics of each issue rather than a predetermined stance. Bias arises when one's position is decided in advance, regardless of the evidence.

"Journalists practicing this classic approach often find themselves criticised by both sides while supported by few. It’s an inevitable outcome of sticking to factual, objective journalism"

CC: What’s the impact of maintaining the classical, fact-based approach?

Journalists practicing this classic approach often find themselves criticised by both sides while supported by few. It’s an inevitable outcome of sticking to factual, objective journalism. We’ve started calling this "unhyphen ated journalism"—an approach focused solely on the issues rather than affiliating with one side or the other.

CC: Do you think the respect for journalists or the media has diminished in the eyes of readers?

Yes, I think it has declined. I even wrote a column on this topic a couple of years back.

CC: What led you to notice this decline?

During the pandemic, I watched several old movies from the 1950s, like ‘Mr. and Mrs.55’, ‘Kalapani’ and ‘Solva Saal’, where journalists were portrayed as heroes, fighting injustice and coming out victorious. They were respected and admired figures. But if you look at recent films like ‘Peepli Live’ or even ‘PK’, journalists are often trivialised or ridiculed.

CC: How has this shift impacted journalists, especially younger ones?

It has led to a trivialisation of their role. For example, Aamir Khan’s shows and movies sometimes mock reporters directly, and I’ve told him this myself. If you trivialise senior editors, that’s one thing, but if you’re ridiculing young journalists on the ground, that’s a different story. Even when he did ‘Satyamev Jayate’, he acted as a journalist but presented a lot of sensationalism and pseudo-science, charging millions per episode.

CC: Has television contributed to this perception shift?

Absolutely. TV journalism, in particular, has taken a toll on the public’s respect for journalism because the role of the editor has essentially disappeared from newsrooms. Star anchors often act as both editor and presenter, with no one to critique or guide them. When your chief anchor is also the chief editor, there’s no one to edit or provide oversight. This creates issues with accuracy and depth, as most don’t have expertise across fields or time to research adequately.

CC: Is ThePrint addressing these challenges?

Yes, at ThePrint, we’re actively working to counter these trends. It requires a lot of effort, but we’re focused on upholding the role of the editor and maintaining quality journalism, addressing the depth and rigour that seem to be missing elsewhere.

CC: In five to ten years, do you envision any significant changes in journalism? Right now, it feels like there’s a storm, with too much upheaval.

Yes, I believe we’ll see a correction and a shakeout. More viewers and readers are beginning to realise that truth isn’t always black or white, nor does it come solely from one side. This shift in perspective will take time, but it’s happening

"The most important qualities for a journalist are curiosity and humility. Curiosity drives the pursuit of knowledge and the ability to uncover stories"

CC: What do you think is fuelling this polarisation, especially when we look at places like the US and other Western democracies?

In many of these regions, there’s growing polarisation, with the right often gaining ground. This is partly because mainstream media is generally perceived as leaning left, so audiences who feel unrepresented seek out other perspectives, often leaning towards the right. I use "left" and "right" here in a broad sense, but this perception gap is impacting journalism’s role in society.

CC: What was the most fulfilling period in your five decades of journalism?

The most fulfilling period was undoubtedly the three years I spent covering the Northeast. It was a challenging experience, but it allowed me to pay my dues and gain invaluable insights into the region. This knowledge has been a valuable asset throughout my career, particularly when reporting on Northeast India.

CC: What was the most fulfilling period in your five decades of journalism?

The most fulfilling period was undoubtedly the three years I spent covering the Northeast. It was a challenging experience, but it allowed me to pay my dues and gain invaluable insights into the region. This knowledge has been a valuable asset throughout my career, particularly when reporting on Northeast India.

CC: As an editor, what was the most challenging and rewarding experience?

One of the most challenging yet rewarding experiences was simultaneously holding the roles of Editor-in-Chief and CEO at ss. It was a demanding task, and I initially had doubts about its feasibility. However, with hard work, dedication, and the support of Vivek Goenka, we were able to make it successful.

CC: What advice would you give to aspiring journalists?

The most important qualities for a journalist are curiosity and humility. Curiosity drives the pursuit of knowledge and the ability to uncover stories. Humility ensures an open mind and a willingness to learn from others. While technical skills like writing and reporting are essential, these two qualities are fundamental to a successful career in journalism.

CC: What is your philosophy of life?

While it's important to live in the present, it's equally important to have aspirations and goals for the future. Building strong teams and mentoring young talent is crucial. The legacy we leave behind is often measured by the people we've influenced and the positive impact we've made on their lives.