Issue No. 8 / April 16,2015

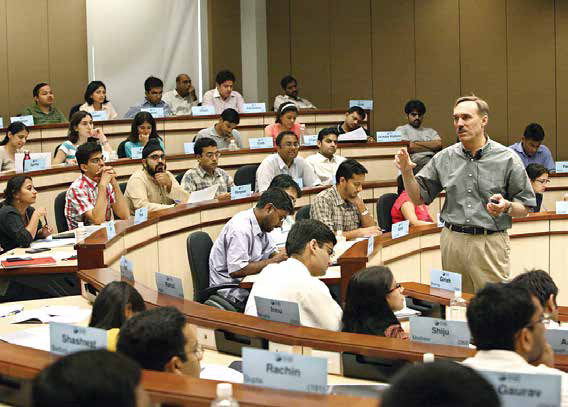

Indian School of Business (ISB) is one of the premier private business schools in India, with campuses at Hyderabad and Mohali. ISB has taken shape with the support of leading corporates of India and abroad along with top global business schools. Its two state-of-the-art campuses are built over a sprawling 260 acre campus in Hyderabad and a 70 acre campus at Mohali. The then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee had stated during his inaugural speech on its opening day, that it is the corporates’ gift to India

Corporate Citizen spoke to the dynamic Dean of ISB, Ajit Rangnekar, an accomplished corporate professional and now a passionate academician. He joined ISB in 2003 as Deputy Dean and has admirably steered the institute, bringing it international recognition and accreditation.

Rangnekar’s career spans over 30 years in the industry, in consulting positions pan-Asia. Before joining the ISB, he was the Country Head, first for Price Waterhouse Consulting and then for PwC Consulting, in Hong Kong and the Philippines. He was head of the Telecom and Entertainment Industry Consulting practice for PwC in East Asia (China to Indonesia). His maiden job was with Associated Cement Companies, India, where he rose to be a General Manager at the age of 30. Rangnekar did his graduation from the Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai, and completed his post-graduation in Management from the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. Read on for his take and vision for ISB.

Corporate Citizen: Your association with ISB began from 2003 when you joined as its Deputy Dean. Now you are its Dean. Tell us about your experience during this 12 year tenure with this prestigious and one of its kind management institute.Ajit Rangnekar: In those days we were a start-up. We had no reputation. Nobody knew us. Hence the first five years went in really establishing ourselves. The next five years were of growth. We have had different experiences. As a start-up it is not the same as an established company. Now of course, as an established institution, ISB does not have to worry about a lot of things, especially with regard to the quality of its students or reputation in the marketplace. However, in the beginning it was a tough job – we had to convince everyone that this institution deserved serious recognition. We hardly had 180 students and we were losing money. With no reputation in Indian School of Business18 / Corporate Citizen / April 16-30, 2015 Cradle of Leadership-7 the marketplace, people had a lot of questions about us. We had to overcome all that – it meant relentlessly meeting and convincing people; talking to corporates, media and to potential students to explain what ISB really stood for. You can talk whatever you want – ultimately it is because your students perform in the industry that your reputation is made. We were lucky to have students of really high quality.

Despite ISB being a unique experiment, which was strongly backed by leading corporate leaders, it is surprising that you faced challenges initially?We always got students, but the industry was not used to looking at students who had working experience in the industry and then pursued their MBA. Traditionally, it was the other way round where you finished your engineering, let’s say, did your MBA, and got placed. We took students from different backgrounds and experiences -- like those who were journalists. In fact, we even had an air hostess in one of the earlier batches. On top of that, we had a one year MBA program instead of the conventional two year program. So there were big questions in the industry about its validity. We had to put in immense efforts to demonstrate that our school was different, and in many cases, better. We soon overcame the hurdles – now the industry respects us. Ultimately when the school performs, you build up a track record.

Before joining the ISB, you were a successful corporate leader, working in multinational companies. Tell us about your very impressive corporate tenure.

The important thing is that even with PwC, my work was essentially with start-ups. ISB was a great opportunity for me to work with a different kind of start-up. An academic world is very different, as building an academic institution is not easy, especially because of the regulatory challenges we have to face in India. Despite the challenges involved, it has been a terrific experience for me and I have a deep sense of fulfilment.

India might have lost ‘In the beginning it was a tough job – we had to convince everyone that this institution deserved serious recognition. We hardly had 180 students and we were losing money. With no reputation in the marketplace, people had a lot of questions about us

Could you tell us about how ISB came into being?Rajat Gupta and John Jacobs of Kellogg School were the two people who thought of building a world class management institution in India. That’s because they believed that after the opening up of India in the early 1990s they felt that India was going to be on par with the world economy. Before that India was a protected and isolated economy. So the1990s defined that India would become a part of the global economy and if it did so, it would need global quality talent that also understands the reality of India. Till then you had global schools like Kellogg and Harvard which understood global standards and then you had indigenous institutions which understood the reality of India, but we did not have any which could bridge both. That is why they decided to set up an institution in India. The original idea was to set it up as part of IIT Delhi, as Rajat was its alumnus, but they realised that you have to build a different kind of institution which may not be possible within the constraints of government policies. That is why it was decided to set up a completely independent institute.

How was the city of Hyderabad chosen for ISB’s location?The original idea was to set it up in Mumbai but the then government wanted reservation for Marathi people. You cannot make a world class institution with reservation – be it students, faculty or even staff. Chandrababu Naidu, the then chief minister of Andhra Pradesh was very keen to bring it to Hyderabad so he worked very hard to convince the Board that Hyderabad was the right location. By that time a large number of Indian industrialists had also agreed to support the ISB. So they were the people who were looking at the location. So Naidu convinced them it should be in Hyderabad rather than Bangalore or Chennai. I think it has been a very correct decision, as Hyderabad has been a wonderful support to ISB. Successive governments have also realised the value of ISB.

How are you different from IITs and IIMs in the sense that you may be in some way obliged to the state government for having given you the land?

So far, it has been a notable contribution of around Rs 600 crore from the corporate world.

What does ISB stand for and what are the courses you offer?Firstly, it is about high quality education; secondly, it has world class research facilities and thirdly, we work with the society to help solve the society’s big problems. We have done extensive research for the finance ministry, the Reserve Bank of India, food security planning, research on improving deliverable services for the Andhra Pradesh government, how to rope in the industry for the Punjab government, for the SME sector and so on. Hence, the government as well as the corporate world has benefited from ISB.

With a strong emphasis on entrepreneurship, the impact of technology on commerce and emerging markets, programmes at the ISB focus on managing business in fast-evolving environments. The ISB works closely with its associate schools and academic area leaders to create contemporary programmes that apply Western concepts into the Asian context. We also have established strong corporate and industry links which ensure that the program curriculum reflects global best practices, is international in perspective, and delivers according to world-class standards. Primarily, we have a one year Post Graduate Program in Management and several short term Executive Programmes.

It is said that ISB was created by the industry to reduce the heavy cost of sending senior executives abroad (such as Harvard, Wharton, Boston and so on ) which in effect means that instead of sending people abroad the industry created a replica in the form of ISB. Please comment.I have never heard this one before. I think the people who created observed that the top 20 business schools in the world had fewer than 400 students from all over Asia – 396 to be precise. That is roughly for half the world’s population. So companies and corporate leaders like Rahul Bajaj said we must create enough capacity in our country so that we can provide world class education to our students. Hence unlike the IITs and IIMs, the ISB has grown very rapidly. In just 12 years, we have 800 students, whereas in 30 years IIMs have just 200 odd per batch. Now of course with the OBC and other quota the number has slightly increased but our philosophy always was that we will create more capacity so that there is enough talent available and enough opportunities available for bright students in India.

I must also add that very, very few of my students joined my Board companies. Most of them joined international companies and the Board is perfectly okay with it. It is perfectly alright. Even for my Executive Education program, fewer than 5 per cent of my participants are from my Board companies. Most of the companies are from outside, and the interesting part is that we do a lot of short term Executive Education programmes for the public sector and for government. It is truly a benefit to the nation; not just to these corporates who have supported. That’s why I say I have never heard that comment before.

‘Schools are not willing to invest in faculty education, because many of them feel that if they invest, that faculty may end up joining somewhere else at a higher salary. Faculty is the single biggest problem – there is no shortage of good quality students

Please tell us about ISB’s international rankings?We were the first Indian school to be internationally ranked in the FT (Financial Times) top 100 schools across the world. ISB is also the first business school in South Asia to be recognised by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB).

Achieving AACSB accreditation involves a process of rigorous internal review, evalu tion, and adjustment. It necessitates meeting AACSB’s exacting standards for a high quality teaching environment, a commitment to continuous improvement, and curricula responsive to the needs of businesses. The AACSB accreditation has been earned by less than 5 per cent of the world’s business schools. The accreditation reflects ISB’s position as a pivotal player which will shape tomorrow’s global management education landscape.

Though you have such an impressive legacy and have also been quoted in international rankings once, you don’t have any recognition by any regulator in this country?We are keen to be regulated, but we are not keen to be regulated such that it hurts my students, and at a cost which completely compromises the quality of education. For example, the AICTE has a regulation that you cannot have more than 280 students and today we have 800 students, which is a matter of pride. Then this regulatory authority tells you how much fees you can charge, what kind of faculty you can take and how much you should pay them. How can I get world class faculty if I cannot pay them? That is not AICTE’s problem. As for the UGC, it refused to recognize a one year Master’s Program. Now, the world over, there are one year Master’s programs. So, can we build a world class institute with such archaic regulations? So we have had to voluntarily decide not to comply by them. It is sad for the country. We are stuck with regulations that don’t get us anywhere.

Did you receive any notices by the All India Council of Technical Education asking you to change your ‘one year’ to a ‘two year’ program, or have you sought any kind of regularization to ensure that your courses are recognized by competent authorities?

It is 100 per cent from the industry, as we treat everyone as industry, be it NGOs or the government. To be specific, it is 90 per cent from industry and 10 per cent from others. What is the age group of your students? The age group is roughly between 23 and 50 years; the average being 27 years. We have about 30 per cent women students and would like to increase it to 50 per cent, but families unfortunately in this country are more willing to encourage sons to do postgraduation than their daughters.

Especially if the fees are as high, as it costs some Rs. 24 lakhs for your one year course…

In fact, we are the most competitive MBA program in this country. Any other program is two years, right? So take some reasonable priced program – it would be about 4-5 lakhs over a period of two years. Ours costs Rs.20 lakhs in the first year and the next year the students earn, on an average, Rs.20 lakh per year. In addition, some people receive scholarships. So, let’s look at it in a different way. If you are doing your MBA here after some work experience, you are earning, let’s say 5 or 6 lakh rupees per year already. In the year that you are admitted to ISB, you do not incur any cost as you get a loan. Next year onwards you start earning about Rs.20 lakhs per annum. On an average you repay your loan to the tune of about 3 – 3.5 lakh per year; still you would have Rs.17 lakhs with you. So where is the cost? You actually incur a zero cost doing an MBA in ISB. That is why we get a large number of students who come from business backgrounds like business and financial communities. I think they understand the matter in the proper perspective. A large number of our students who come from the industry fund their education through loans that are student friendly and collateral free.

‘The biggest difference between IITs, IIMs and us, is that we are not constrained by unnecessary regulations... any constraint in the regulations would have made it difficult to create a world class institute

Do you think that prior work experience should be made compulsory for anyone to pursue an MBA degree program? Many American universities insist on ‘prior work experience’before they join the MBA program. Do you think such a condition should be applied in India? If so what will happen to the masses aspiring to join the industry?

In business education you have a three-way learning – first, the concepts, from the best faculty; second, from applying those concepts to your own experience; and third, even if you have some experience and if a faculty teaches you, you may not have worked in that kind of an environment, or your experience is only one kind of experience in one environment. If you have exposure to another experience, then you learn from that also. That is why you need to have experience and you need to also have diversity of experience.

What do you think about the focus of MBA institutes in the country?I actually think there are fewer than maybe, at the most, 100 institutes which are really teaching well with good faculty; who are trying to understand the issues facing the industry and making effort to equip their students with the right skills. Most others are probably low quality shops. Some may be well intentioned; some may be money making machines – we don’t know.

Undoubtedly, out of the 3000 odd institutes approved by AICTE at one time, a very, very large percentage are not adding enough value to justify the fees. That is why new regulations and approach is necessary. I am not saying the country does not need 3000 institutions; it needs more; but where is the quality? How is ISB different in terms of faculty and curriculum?The sad part in this country is that an MBA is considered lower quality than PGDM. Curricula are not changed regularly. We have been trying for the last few years and not succeeded as much as we would like to and that is to train teachers from other colleges to improve their capability. Schools are not willing to invest in faculty education, because many of them feel that if they invest, that faculty may end up joining somewhere else at a higher salary. Faculty is the single biggest problem – there is no shortage of good quality students. There is more than enough talent in India; if only they had good curriculum, faculty and industry-connect….

‘The AACSB accreditation has been earned by less than 5 per cent of the world’s business schools. The accreditation reflects ISB’s position as a pivotal player which will shape tomorrow’s global management education landscape’

As for ISB, our faculty do a lot of research themselves, so what they teach in the class is not somebody else’s thinking but their own experience and analysis. Secondly, all our faculty are PhDs, and come from the absolutely top 25 PhD programs in the world. We expect our faculty to do world class research throughout their tenure here so that they continue to stay up-to-date. Lastly, we regularly update our curriculum

What is your advice to MBA students? Do you think they are on a wild goose chase to earn money?All I would say is that doing your MBA is not the only way in which you can find fulfilment. Right now we have a young professor who is actually developing a course on happiness. Why do you earn money? In order to be happy. So, first figure out what is important to you in life. Don’t go like a herd of sheep. Now, with the internet, you can get information on what you want to do, and besides this external information, you need to introspect as to what you really want to do in life. What do I really enjoy doing? If you don’t know that, then what problem are you trying to solve? Also, what we strongly need is high ethical standards – you cannot and must not compromise. This I feel is the single most important thing.

Tell us about your family.This is one thing I don’t like to talk about for two reasons – one, I like to keep my family out of public view, and the second part is that I feel extremely guilty. I’ve really not been fair to my family and my friends as I’ve not been able to spend enough time with them. If there is one source of regret for me, then it is that I’ve sacrificed a lot of my time for work.

By Vinita Deshmukh