Issue No.21 / January 1-15,2015

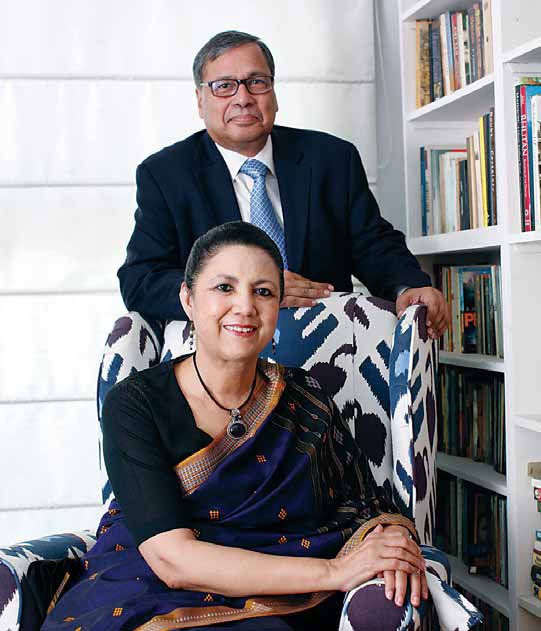

Many a romance has bloomed in Mussoorie and so did ours. We decided to get married in 1975

What does it take to be a successful diplomat or bureaucrat? What heady challenge does one find in these roles? What goes into the making of a successful marriage despite chasing parallel professional paths even across the seven seas? What higher calling motivates and propels one to serve in the civil services? This time’s dynamic duo, diplomat Meera and senior civil servant Ajay Shankar have the answers

Meera Shankar joined the Indian Foreign Service in July 1973 and had an illustrious career spanning 38 years. She has extensive experience on South Asia, USA, Europe, security and economic issues. She served as Director in the Prime Minister’s Office from 1985 to 1991, working on foreign policy and security matters. She was then posted to Washington DC and served as Minister (Commerce) from 1991 to 1995. Thereafter,she headed the Indian Council for Cultural Relations overseeing India’s cultural diplomacy. Subsequently, in the Ministry of External Affairs, she headed two important divisions dealing with the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and relations with Nepal and Bhutan. As Additional Secretary, she held the responsibility for the United Nations and International Security. She served as Ambassador to Germany from 2005 to 2009 and her last assignment was as Ambassador of India to the US from 2009 to 2011. She is presently appointed as Non-Executive Independent Director on the Board of ITC Ltd and is also on the Board of Pidilite Industries Ltd. She also serves on the Board of Trustees of the Alfred Herrhausen Society, the not-for-profit international think tank of the Deutsche Bank and the Governing Body of IRADE, a Delhi-based think tank focusing on energy, environment and gender issues.

Corporate Citizen spoke to both of them to get an insight into their respective dynamic assignments and how they held each other’s hands to facilitate each other’s success

Ajay Shankar joined the Indian Administrative Service in 1973. He has a Master’s in Political Science from Allahabad University and a Master’s in Economics from Georgetown University, Washington DC. He taught Political Science at Allahabad University. He has rich experience in industrial policy and promotion, the energy sector and urban management and development. As Secretary, Department of Industrial Policy & Promotion in the Commerce and Industry Ministry, he played a critical role in putting together various stimulus packages and policy decisions to improve the competitiveness of the Indian industrial sector. As Principal Adviser in the Planning Commission, he looked after the water, sanitation and environment and forest sectors. As Joint Secretary/Additional/Special Secretary in the Ministry of Power, he played a key role in the preparation and enactment of the Electricity Act, 2003, the rules and policies under the Act and conceived the national programme, the Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vidyutikaran Yojana, for completing rural electrification. He also served as CEO, Greater NOIDA Industrial Development Authority, as Secretary to the Lt. Governor of Delhi for over five years, and Chairman, Kanpur Development Authority. After retirement he was a Distinguished Fellow with TERI and a public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington. He has served on the Board of IDBI, EXIM Bank, NTPC, NHPC, PFC, REC and Tata Global Beverages Ltd.,and as Chairman of the Damodar Valley Corporation. He has been a member of Committees on reform of public sector undertakings, electricity distribution and resources for the power sector for the 10th Plan, besides being associated with the design of the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission. He is currently chairing the Expert Committee on pre-investment approvals set up by Government and is also advising the Railways on their PPP set-up.

I can’t say that I was so focused when I was young. In school, I wanted to be an athlete as I used to run the 100/200-metre races, do high jumps and play basketball. Later I wanted to be a writer, so I can’t say I was that focused. By the time I finished college and was pursuing my Master’s from St John’s College in Agra, I thought, maybe I could pursue the civil services. Subsequently, that became my career choice.

My father was in business, but was always very supportive of his daughters working. He used to say, “It is my job to give you a good education. Then you have to stand on your own feet.”

I joined the IFS because I was interested in international relations and world affairs. I felt this would be an interesting career, because you get to see different places and different cultures and also have the ability to contribute to your country’s national goals through your work as a diplomat.

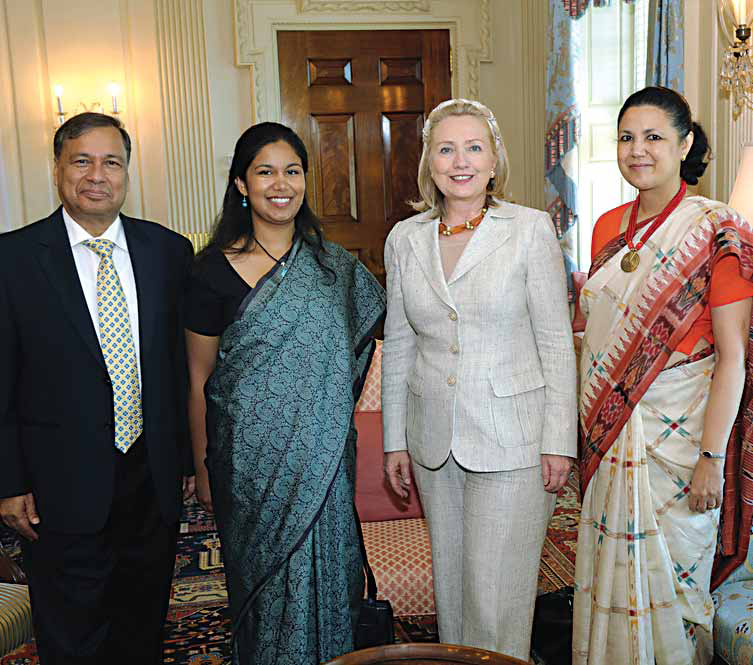

I was the first professional woman diplomat to be posted as Ambassador to the USA and the second after Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, who was a political appointee. I was the Ambassador to Germany, when I got the posting to the US. I was both excited and a little nervous because it’s a huge responsibility.

We met in the academy in Mussoorie when we were under training, after we passed our civil services exam. That’s a great place for young couples. Many a romance has bloomed in Mussoorie and so did ours. We decided to get married in 1975, despite the difficulty of him being in the Administrative Service and me in the Foreign Service. There was quite a bit of advice to me in particular, that now that I was married, I should think of settling down, which meant give up my career. I thought, let’s see, I am sure we can make it work. Thankfully, we have been able to make it work.

We have many common interests—literature, reading, music, theatre, walking, interest in development issues and in the world around us. I think I was attracted by his intellect. He is deeply intellectual and a very kind person.

In those days, the Foreign Service used to be very competitive and very difficult to get into. Only the top twenty or so got into it because the number of vacancies were so few. Even though Ajay could have chosen the Foreign Service on the basis of his performance, he had opted for the Administrative Service.

We adjusted in the sense that Ajay took leave,sometimes without pay, and I also opted to be in Delhi for long periods. It was a great experience and a very hard slog. The Government too was very facilitative. They did allow Ajay to take leave and come with me. Once he took study leave and did his Master’s in Economics, from Georgetown University. When I was Ambassador to the USA, he had retired, so he joined me. While I was in Germany, he was Secretary here in Delhi. We met whenever he had to go to Geneva or Vienna on work, then he would always spend the weekend in Germany.

I was a junior officer, a Director, but still there was an enormous amount of work, and long hours. The great thing was I got to work with Rajiv Gandhi, VP Singh, Chandrashekar and Narasimha Rao, and each had their strong points, their own way of looking at things and working. It meant that you had to prepare the information and briefings in a way that that particular prime minister preferred. The unique aspect was that you got a 360-degree view of policy and an opportunity to contribute across the spectrum. Otherwise, at that level you dealt with a limited area, like South Asia or East Europe. That was quite exciting for somebody that young. About my tenure with these four prime ministers, each one was fulfilling in a different way. These were tenures when I worked the hardest. On one occasion I worked 36 hours without a break.

The first one was as Minister heading the commercial and trade wing in the Indian Embassy from 1991 to 1995, I was given a year’s extension. That was a good time because the economic reforms had just happened in India in July 1991 and I went in September 1991 to Washington. I had a story to tell and because of the changes that were taking place in India there were new possibilities for trade and business. We were able to generate quite a lot of attention and interest in India. For instance, the US named India one of the ten big emerging markets worldwide and for the first time, all the key economic secretaries—which is the equivalent of their ministers—visited India. Commerce Secretary, Ron Brown; Energy Secretary, Hazel O’Leary; Treasury Secretary, Robert Rubin who was also National Economic advisor to President Bill Clinton, visited India during that time. We also set up the India-US Commercial Alliance, which had ten CEOs from either side and they would meet with the commerce ministers every year, to brief them on their issues and get Government attention to put in place policies which would facilitate trade and business. Later on this was upgraded to the summit level, so the CEO forum now reports to the Prime Minister and the President. I think it was the first time our trade expanded, investment from the US began to increase and many of the key companies began looking at India with renewed interest. It was a good time to be heading the Commerce wing, in the Embassy. The Embassy had different wings like political, defence, commercial and economic. When you are Ambassador you oversee all of it. As Ambassador I had the satisfaction of seeing the India-US strategic dialogue take off, completing the agreement on reprocessing of nuclear material, expanding defence cooperation and achieving liberalisation of US Export Controls on High Technology for India. For the first time the US declared support for India’s Permanent Membership of the UN Security Council in President Obama’s address to Parliament in November, 2010.

As a diplomat you are constantly engaged in building up the relationship, resolving isues and creating opportunities, particularly while dealing with business and economic cooperation between India and the US. That is a huge challenge. You have to be very outgoing. You have to reach out to different constituencies, connect with Business and try to interest them and find ways to address their issues, connect with the U.S. Congress, connect with the media and think tanks, and connect with the Government to get problems resolved. Also, when you are living in the US you are trying to understand and adjust to that society.

When I first went to the US as Minister (Commerce), there weren’t that many women visible in the US administration or even in business. The second time when I went as Ambassador, things had changed. Hillary Clinton was Secretary of State and she had been preceded by many women in the field of foreign policy, including Madeleine Albright, Condoleezza Rice and now, Susan Rice. In 1991, you would only see men in grey suits by and large, but by this time there were many women visible in the boardrooms, in business and in the administration. The US as a society appreciates merit and if they think you have something to say or contribute, they pay attention, irrespective of whether you are a woman or man. But still it’s a challenge, for instance a woman has still to find acceptance as President of the US.

When I first went to the US as Minister of Commerce, there weren’t that many women visible in the US administration. The second time, Hillary Clinton was Secretary of State and she had been preceded by many women

I had her when I was a little older, which was nine years after we got married, because initially we were too busy with our careers. By then I was ready to have a child and that’s important. You must have the mental attitude that you want the child. We managed by supporting each other. I was fortunate also that my mother came to live with me in Delhi. I took maternity leave. During my pregnancy I was working with Indira Gandhi’s Special Envoy to Sri Lanka, G Parthasarathy. I had a very busy time and he was a hard taskmaster. I was working till the last minute. I took leave after the doctor said I could deliver at any time. However, I was called back the next morning as there was a debate in Parliament and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was going to respond to it. She had raised certain questions and wanted answers to the queries she had raised. So I was called to the Foreign Secretary’s office and told to prepare the answers to these questions. Then Mr Parthasarathy said I should go and sit through the debate too. He stated jocularly that, the Parliament was air-conditioned, and the baby born in Parliament would get some special privileges! So I went to Parliament and sat through the debate on Sri Lanka. Many of the MPs from Tamil Nadu were thundering away on the issue. The debate finished at about 7:30 pm and my labour pains started at about 9:30 pm and then I was rushed to the hospital. I never had any trouble during my pregnancy. I was too busy to know how it went by.

I resumed work three months after, but not full time, as I got a three-month overlap with somebody. In a sense I was working part-time at that stage. After my six months off work, Ajay took leave for a few months and my mother was also staying with us. That was a big help. I never had any worry. Even when I did some hectic assignments in the Prime Minister’s Office or elsewhere, I was always perfectly secure that my daughter, was in good hands.

When I went to the US as Minister, (Commerce), Ajay took leave and did a Master’s in Economics in Georgetown University, because my mother could not come with me for the first year. He would be at home with my daughter in the afternoon and evening.

She really was a very gentle child; also, some-body who was very conscious of not throwing her weight around. I don’t think we had to instil it in her, maybe she imbibed it unconsciously, but she has been a very gentle and polite child always.

When she was passing out of elementary school in Washington at the end of class five, the students have a fun vote on, the student most likely to become the President of the United States, the student most likely to join Hollywood, the student most likely to be in the national football team, and so on. They voted my daughter as the student most likely to win the Nobel Peace prize.

You have to be very observant, because you have to constantly take in what you are seeing and analyse it, assess and send your assessment back to the Government. You have to be objective, because your reports must always be honest. If, for some reason, you do not convey an accurate picture, your Government can get misleading assessments and therefore take wrong policies. You have to be very outgoing, because you have to make contact with a large number of new people and gain their trust each time you are posted to a new country. You have to be able to understand the perspective of the country you are posted in. You have to have the ability to communicate, because you have to persuade people and you have to convey your nation’s position in a persuasive manner. You must be patient and discreet. Premature disclosure can sometimes thwart agreement on sensitive issues. You must also have the ability to adjust, because you are constantly changing from one country to another. Public speaking is a big part of your work. But say you are dealing with a small South Asian neighbouring country where India looms very large in the public imagination. Then you have to temper your public role and be more discreet, because you don’t want to appear dominating. You have to adjust to different circumstances and sometimes, you even have to work in hostile environments. For instance, our diplomats who work in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal or Sri Lanka have faced a lot of difficulties on occasion and sometimes had to be provided special security when they had internal challenges in these countries.

You have to be very outgoing, because you have to make contact with a large number of new people each time you are posted to a new country. You have to have the ability to communicate, because you have to persuade people and you have to convey your nation’s position in a persuasive manner

If you look at the German and Indian approach to an issue, the German approach is to create systems. They spend a lot of time planning in great detail, anticipating different contingencies. They create excellent systems which function very smoothly. But if something goes wrong in that system, they have difficulty changing course suddenly and being flexible. Indians are atrocious at creating systems and that is a huge institutional weakness, and that’s why they have to rely on individual ingenuity. Which is why the quality of our administration tends to be uneven. If you have a good officer, then the administration functions well. When his/her replacement is not good, suddenly you see a big dip. That is because we have not been able to systematise to the extent we should.

The fact that he was there in Washington when I was posted there, was a huge help. He was very cool about it, because in those days it was not so common to have the wife working and the husband on leave. Now you do see it. When people asked Ajay about it, he answered that he had all the privileges of diplomatic life without any of the responsibility! However, we keep our work apart. Of course, we discuss general national issues and developments, but by and large we have kept our careers apart.

Firstly, both sides have to be willing to make it work. If only one side makes the adjustment, it becomes difficult. If the wife expects that only the husband will make the adjustment, that won’t work and if the husband expects that the wife should make all the adjustment, that also won’t work. It has to be mutually supportive and both must have the willingness to put the marriage above their careers at some stage, because if you want to pursue your career without seeing how it impinges on the marriage, then at some stage the marriage may become weak. We always felt that it is important for us to try to stay together and if it means that Ajay makes the adjustment or I make the adjustment, we will do it to stay together. As it happened, we were fortunate enough to have good and challenging assignments while also managing to stay together, most of the time. Friendship and respect, both are extremely important. Romance is very heady, but for a marriage to sustain beyond romance, you need to be friends.

My daughter and her British husband met while they were in Oxford and they were together for quite some time before they decided to get married. They took long to make up their minds, but once they made up their minds, they got married very thoroughly—once in India the Hindu way and once in the UK in a church wedding!

Firstly, don’t harm anyone and try to do good for the larger society. Commit to something beyond yourself and beyond your family, which is larger than yourself.

Because the kind of responsibility and the kind of opportunity that you have in Government is unmatched. At the end of the day, you have to feel that you have contributed something to society and the Government gives you unparalleled opportunity to do that. Don’t join the Government if you want to become wealthy. Don’t join if you want to use your position for personal gain. But do join the Government if you want a truly challenging assignment. If you are a district magistrate or a diplomat overseas or a police officer, the kind of responsibility you have at the age of 30 is unmatched. It is unfortunate that increasingly the quality of our administrative system is becoming fragile with many pulls and pressures. So as a Government servant you also have to have the ability to withstand pressure and be able to do what is right.

When I finished my education there were few opportunities in the private sector. Government was the main employer. Today there are so many opportunities. Still I would say that while we need bright people in the private sector, we also need bright people in Government. If all the bright people choose to stay away from the Government, you will get a third-rate Government. In every sector, especially in India, the Government still looms very large. In terms of infrastructure, in terms of services, we are still not at a stage where our social and economic development is mature. It is Government policy and investment that will drive or hold back the process.

By opportunities I mean, first of all there is huge responsibility. Secondly, the very diverse fields in which you can work. For instance, as a diplomat, I was involved with strategic issues when I was Additional Secretary, UN and International Security; the nuclear negotiations with Pakistan, the CBM agreement that we signed with them on Pre-Notification of Ballistic Missile Flight Tests. I have done cultural work as Director General of the ICCR (Indian Council for Cultural Relations). I have done economic work as Minister, (Commerce) in the Indian Embassy in the US. So, the variety of work that you get to do, plus the enormous challenge of development. If you are in a developed nation, the challenge in Government would perhaps be far less. But in a society where so much remains to be done, even if you succeed 30 percent of the time, you have done enormous good. The number of people you affect would be so huge. In a developing country in particular, you need good people in Government. Of course, young people should follow their talent and inclination, be it sports, sciences, arts, business or Government and employment will primarily have to be driven by the private sector.

Not really. There are different phases in life and as per Indian tradition it is said that in the first phase you are a Brahmachari or student, the next phase you are a Grahastha or householder, then you are in Vanaprastha or hermitage, and finally Sannyasa or renunciation. You have to accept that there are different phases of life and be alert and active in different ways.

Friendship and respect, both are extremely important. Romance is very heady, but for a marriage to sustain beyond romance, you need to be friends

Ajay:I grew up in Allahabad, which, when I was growing up, was a great place. I went to school and university there. Initially, I thought I would be a physicist as I was a National Science Talent scholar, but after I graduated in Science, I came to the conclusion that if I wanted to be a first-rate physicist, I needed to go to the USA. On second thoughts, I felt I should get into public service. This then made me do a Master’s in Political Science, after which I taught the subject in the Allahabad University for two years and then gave my civil service examination. I finally decided upon a civil service career, not so much for prestige and power, but genuine desire for public service. When I joined the Government, India was at the stage of its development and evolution where there were many opportunities to do things that made a real difference. It remains so even today.

I often had the good fortune of being in the right place at the right time. I was lucky to spend about seven years in the Power Ministry, from 1999 to 2007. I was associated with the Electricity Act of 2003 from the day it was thought of, to the day it was enacted and finally notified along with its Rules and policies. It was one of the major reform legislations of the NDA Government. It provided for the establishment of the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission and the State Electricity Regulatory Commissions, rationalisation of electricity tariffs, transparent policies regarding subsidies, promotion of renewable energy and competition. The law as it emerged was very progressive, and got a lot of appreciation across the world. It created the enabling regulatory framework for the emergence of a competitive industry structure with increasing private sector participation.

I was again fortunate that, while in the Power Ministry, I was able to work on the massive programme for completing rural electrification. When we began looking at the issue seriously around the year 2000, roughly 1,25,000 villages in the poorest parts of India— Eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Odisha and Assam—did not have access to electricity. We were able to launch a national programme under which over one lakh villages have been electrified and household access to electricity in India has moved up dramatically from about 56% in 2001 to about 78% now. The Government is now aiming to complete the work of electrification by providing full, uninterrupted access to electricity to all in the next few years.

The National Solar Mission was launched in January, 2010. The Mission set the ambitious target of 20,000 MW of solar power by 2022 and aimed at reducing the cost of solar power in the country through long-term policy with, large-scale deployment goals and increasing domestic production and value addition. The objective was to achieve grid tariff parity. I was again fortunate to be part of an expert group which worked out the details for Phase I of the National Solar Mission. The contribution I was able to make was to argue successfully that we needed a competitive industry structure and should go for tariff-based bidding for solar power plants. This would push prices down. Five years down the road, we have been more successful than I thought we would be. Tariffs have come down dramatically and are near grid parity. India is now scaling up its solar program manifold with confidence.

‘Make in India’ is neither a mission nor an aspiration—it is an urgent necessity for India. As we are set to be the world’s most populous country by 2028, our social stability will depend on its success — Ajay Shankar

Before the 1991 economic reforms, there was a huge gap. There were adversarial perceptions about corporate India in the Government. I recall a senior civil servant telling me with great pride that he would make industry leaders wait routinely before he met them in office. Since those days we have moved a long way. Now we are working together and it’s been a transformative journey. But working together in a very pragmatic way on details and on the fine print of policies and programmes is the next stage we have to evolve to. That partnership is beginning to happen, but we need a lot more of it if we have to succeed with Make in India. The role model I have for this is Germany. There all stakeholders—industry, finance and government leaders—are able to have pragmatic discussions without taking public adversarial positions and arrive at decisions that serve Germany well. We need to take India towards that direction.

People in Government and business can work well together. It is not a problem. In India, people from different backgrounds can come and work together. Indians can go anywhere in the world and work well. What we do need is a greater internalisation of the reality that India’s success has to be achieved through the private sector, which has to create jobs, which has to innovate and which, with the right set of policies would also give us inclusive growth and more equality.

Make in India is a necessity. We have to succeed, and the Government is committed politically for its success. Now it is for the different wings of the Government, industry leaders and civil society to work together pragmatically, to put together a finely-tuned granular policy and regulatory framework and programmes which will really allow us to achieve our potential, which is enormous.

Make in India (MII) is neither a mission nor an aspiration—it is an urgent necessity for India. As we are set to be the world’s most populous country before 2030, our social stability will depend on the success of Make in India, considering its potential to generate jobs, especially for those at the bottom of the pyramid. We are already the third or fourth largest market for various products, but we need to concentrate more on creating value in India for both the domestic as well as global markets. It is the only way to generate employment for the large pool of young people joining the labour force every year.

Labour laws need to change to incentivise investments in labour intensive manufacturing. The fact is that industry is reluctant to put up plants which employ 50,000 to 1,00,000 workers. With the easing of regulations and approval processes, setting up of four labour codes in place of 44 labour laws, support to start-ups, and other pro-industry policy measures, more investment should flow into labour intensive sectors where we have been lagging behind. I believe we could achieve our target of generating 100 million jobs in the coming decade if we could generate a national consensus and move quickly with the necessary changes. It is estimated that 100 million manufacturing jobs will move out of China due to higher wages in conventional sectors like garments. We need to build a strategy and create a friendly ecosystem for labour intensive large factories so as to capture at least 50% of these jobs.

The Chinese have achieved enormous success. Seen as the factory of the world, they have practically got rid of poverty, their per capita income is many times ahead of ours. We have to think how we can get rid of poverty, how we create a better life for our people, be good to the environment, have more inclusive growth and more social harmony. Instead of comparing ourselves with China, we need to look at where we are and where we need to go and how quickly we can get there. With 8-10% growth rate, successs in employment-intensive economic activity and creating thereby 100 million jobs, we would have a prosperous society with a good life for our people. At that point of time, where China is would not be very relevant.

Innovation will be the key to surviving and being successful in this century. Firms are beginning to see that. What we need is better public-private partnership to drive innovation and technology development. More than that, the most important thing is that we need to create the ecosystem for start-ups and incubation.

That’s not true. If you recall the old days, people would get imported products and when they went out of order, somebody with some jugaad would set it right. So it’s not that innovation was not there. We have had a stratified and hierarchical society, with a social divide between those who worked with their hands and those who worked with their minds. The two have to work together.

I was lucky to be the CEO of Greater Noida way back in 1995, when it was in its infancy. We were fortunate that we were able to get FDI of about 1-2 billion dollars in two years in those days in manufacturing. We got the first large Japanese investment with the Honda car plant. We got investment from LG and Daewoo Motors. During that period we got more FDI than most states in India, including the frontrunners. Greater Noida had the advantage of being close to Delhi, but what we provided was good infrastructure, private distribution of electricity and expressway connectivity with Delhi, which now has been extended to Agra.

My advice will be to respect one’s inclinations and have a realistic assessment of one’s capabilities and then choose what is best. One can be an entrepreneur, artist, writer, designer, join the Government or corporate sector or teach. The good thing about India today is that all these openings offer a fairly decent standard of living and enormous opportunities to do good things and derive satisfaction and a sense of fulfilment.

Work together to make India great. India has the potential of being a great nation. We have all the talent and ability and everything right. All that we need is to work together as a team. Youngsters have great confidence, energy and ambition. They could do with a lot more self-discipline and hard work.

BY VINITA DESHMUKH