Issue No.16 / October 16-31,2015

wenty-eight years of very tough army life... how does one describe it? The Initial years were spent on the borders where firing of small arms was a routine matter. In these remote areas, small skirmishes, a few deaths here and there on both sides of the border were also common. Moreover, it was extreme cold; no electricity; no water bottles; no newspapers; no television and no entertainment. Varied people from diff erent states lived in harmony together; differences hardly cropped up. Luxury for us meant mutton and rum for three days in a week with four packets of Charminar cigarettes. Entertainment for us meant playing volleyball and basketball on the hills. Above all, our offi cers were magnanimous – they would play along with us, train shoulder to shoulder, joke around and were very caring towards everyone.

Each one of us was leading a tough life. But, we were extremely happy and were always in an exciting mood. Th is is because the leadership in the army is such. Maybe, it is so, in other armies all over the world.

Army is not a service sector, nor is it a place for a normal career. Here, martyrdom is the goal. The country comes first. The safety and security of the people of the country is foremost, but not the family. That always takes a back seat. The uniform converts a person into a soldier and he metamorphoses into an altogether different character, attitude, knowledge and skills. Lakhs of such soldiers are deployed at all places deemed as problematic. Which means, anything can happen anytime. And the soldier is ready to face the consequences, not bothering about his own safety or life. In fact, he is always looking forward to it. ‘How does this transformation of a civilian with so many desires and ambitions get into the world of voluntary mode of ‘my country’ rather than ‘my family’?’ Th e army culture is responsible for that.

It is the offi cers who design and regulate the mind-set and the disciplined behaviour of the soldiers. They are tough like a father. They stand with you when you are in trouble like a good friend. They guide you like a responsible teacher. They fight for you like your own brother. Army officers are an epitome of Genuineness

Let me highlight one experience to illustrate the kind of concern an officer has for his soldiers

It was in the late 1960s. I was posted at Leh in Ladakh. Th ose posted there are allowed to combine their leave for two years. Th is means, one can take four months of leave at a time. Normally, a posting to this place is meant for only two years because of insuffi ciency of oxygen in the High Altitude area which is highly hazardous, medically. Anyone posted there gets High Altitude allowance of Rs. 70 per month. Th at’s Rs. 70 over and above your normal salary of Rs. 240 per month. Therefore, I wrote an application with a request to continue to serve there for another two years which is not normally accepted, but it was, in my case. So, I collected and saved all the money for the marriage and took a four-month leave.

Typically, the army personnel carry a black box, made of metal. I put all my money in it and a lot of items which I had bought from the CSD canteen and went to the military airport at Leh. Roads there are closed for four months due to winter season. And when I talk of aircraft , one should not imagine any of the aircraft of these days. That used to be a big aircraft which brought supplies. After supplies were offloaded, the space which was available would be occupied by some men taken on board. It had no seating arrangement and even getting to fly in it was very difficult as there used to be a very long waiting list.

So, I reached the airport and was waiting as there was no fixed time for the supplies aircraft to come. To fight the extreme cold (it was snowing too), I decided to have a cup of tea in the adjacent military hut which had a small tea-stall. I had my tea and when I returned I was shocked to see that my strong, big box was missing. Mind you, it was an exclusive airport only for military people and yet it was stolen. I didn’t know what to do. All the money was lost. My marriage plans were shattered. How do I go to my home now? I walked back to my unit (37 Coorg Medium Regiment). I went to the hut, cried, and had three pegs of rum.

At around 9 p.m., Capt. K J S Dhanjal came to my hut. He saw me, hugged me and told me that these things do happen; and not to worry too much. He asked me not to cancel my leave and handed over a blank cheque to me. Th en he said, “Go to Delhi and you can draw as much money you want from the bank.’’ That is a sterling example of military leadership. Next day, he took me to the airport and ensured that I was on that supplies plane. On reaching Delhi, I did go to the Karol Bagh branch of his bank and withdrew Rs. 7000 from his account (that was the total amount he had in his account). That much was the amount of an Army officer’s salary in those days. In order to repay, I started borrowing money at an interest of 10%. It took me 10 years to clear my debt

Time changed. I was now a triple post- graduate and my professor M.S. Pillai (later the founder director of SCMHRD and later on Sadhana Learning Centre) wanted me to join SIBM. By that time, I had completed 27 years and 6 months in the Army and a promotion was on the cards which would have led me to serve for another fi ve years. I was serving in the Artillery Centre, Nashik Road Camp. I applied for an early retirement but it was not granted because of the shortage in my cadre at that time and also because my wife and children had submitted a petition to the Commandant not to grant me the pension as they felt that my decision to join education was not a worthy one compared to the promotion in the Army! I was not aware of this petition. Ordinarily, whenever such a petition is received from the family members by the higher authorities, it is very carefully considered by them as Army gives importance to the family system. But I was keen to take up this off er. I had therefore no choice but to approach Maj Gen Y K Yadav who was then Assistant Adjutant General in the Army Headquarters. On reading my inland letter, he called me up and told me “You will prove to be a best professor. Don’t worry, I am coming there for an inspection and I will take up your matter personally.’’ He did visit the Artillery Centre, took up my case and got my retirement order, by hand.

Army is not a service sector, nor is it a place for normal career. Here, Martyrdom is the goal. The country comes first. The safety and security of the people of the country is foremost, but not the family. The uniform converts a person into a soldier and he metamorphoses into an altogether different character, attitude, knowledge and skills.

Why did he say that I will prove to be a good professor? In order to drive home the point, I need to shed off my modesty a bit: I was known to be a very hardworking and result-bound performer. I was always multi-skilling and time was never an issue. I believed in relaxing only aft er completing my tasks, no matter how long it took to complete them. Thus, Army officers always liked to have me on their staff , as their personal assistant, or in any other such capacity. That gave me a lot of insight into the work and life of the officers, their families and their leadership styles—how do they motivate lakhs of troops, to the extent that a soldier is inspired to fi ght for the cause of the country, goes beyond all motivational theories taught at renowned management institutes. This space would not be sufficient for me to narrate the many such exercises of motivational leadership.

It is pertinent though to mention here that the Army is the most democratic organisation where everyone across ranks can have their say freely, frankly, bluntly and yet decently within the framework of custom and tradition—which is of supreme value in the Armed Forces.

I would like to narrate another incident which portrays the high-quality and magnanimous military leadership we have.

When I was posted at the Artillery Centre, Hyderabad, as per the military procedure, the educational qualification needs to be notified and put in the dossier. For that purpose, I had to attest my post-degree certificate, for which I had to approach my superior officer in the training branch of Artillery Centre. R. S. Alwar was the Training Major (an officer in-charge of training) of the entire centre where 5000 recruits were being trained at that point of time. Colonel R. K. Nanda was the Commandant

Perhaps Major Alwar had informed the Commandant that one of the Junior Commissioned Officers (JCO) had become a post graduate. So I was called by him.

Entering the Commandant’s office meant a lot to me as it was very difficult to get an audience with him, and I was trembling from within. He, however, made me feel very comfortable and shared his thoughts. He said he wanted to write a novel and I should take dictation and submit the draft to him. I politely declined. I explained that I did not know shorthand and therefore I wouldn’t be efficient in this assignment. He said, “It’s okay,” and then added, “Did you give a similar reason to General P.P Kumaramangalam, DSO (Distinguished Service Order) when you were in Artillery Centre, Hyderabad?” I nodded. He then prodded, “What was it about? Tell me.”

The story went thus: Since the Personal Assistant (PA) of Col Tapan Kumar Bose, the then Commandant of Artillery Centre Hyderabad, was on leave, I was made to man his office for a few days (this being a ‘selection’ post, only the best are sent there). General P P Kumaramangalam (retd) who was then Chairman of the All India Sports Council had come to the Artillery Centre and was staying in the Officers’ Mess. The General wanted someone to take dictation. He was the former Chief of Army Staff, who had led the 1965 Indo-Pak Operations. His brother, Mohan Kumaramangalam was a Union Minister; his father, Subba Rao, was a noted economist and Governor and his sister, Parvathi Krishnan was a Communist Party leader and an MP. Theirs was a highly acclaimed family from Tamil Nadu

It is pertinent though to mention here that the Army is the most democratic organisation where everyone across ranks can have their say freely, frankly, bluntly and yet decently within the framework of custom and tradition—which is of supreme value in the Armed Forces.

General P. P. Kumaramangalam went on dictating very slowly. I completed the dictation. Then I politely asked, “Can I say something to you, Sir?

He said “Yes.

I said, “Sir, your proposal about Swimming is difficult to implement. There are better ways of promoting swimming.

What I admired about him is that he did not snub me but instead asked me with a smile, “Why do you say so? “This is the kind of leadership which is prevalent in the Army. It is not dictatorial, as generally presumed by the public

I replied, “I feel there are other ways to improve state of swimming as a sport in the country. Every village has a pond (talab). The competition should start at the school level in such talabs. Sir, your suggestion that every district should have a swimming pool and training made available to promising swimmers there, won’t work. Why don’t we train them in these natural waters in the villages, select a team and hold a district-level competition. This should be followed by a state-level competition. You can also suggest that swimming should be made a compulsory part of education. The district officer should be made in charge of this talent hunt. Also, every state has a sports association which is funded by the government, so additional funds would not be required.”

He listened to me intently and I can say with pride that he was impressed with my suggestions, as he incorporated them in his recommendations. Not only that, he mentioned in his forwarding letter that such unconventional methods should be experimented with.

Since General Kumaramangalam was also the Colonel Commandant (a position after he retired as the Chief of Army Staff), he must have discussed it with others and it became a bit of gossip; so obviously the Commandant, Colonel Nanda knew about it and hence asked me to narrate what had transpired in Kumaramangalam’s office. The very fact that the Commandant called me and had a 15-minute chat with me, made me a hero amongst the staff there.

The position of the Commandant of the Artillery Centre got upgraded to that of a Brigadier and Brigadier Nirmal Sondhi took over as the next Commandant of the Centre. In his briefing, Colonel Nanda had told Brig Sondhi that there is an excellent post-graduate soldier serving in our centre

Brig Sondhi excitedly called me to his official bungalow which is called the Flag House. He treated me to a good lunch and told me he wanted to pursue MA and therefore had taken admission in Punjabi University, Patiala for a Distance Learning Programme. And, this being a distance learning one, he was required to submit a lot of assignments. So the responsibility of helping him in the assignments fell on my shoulders. Brig Sondhi inspired others and soon, his Deputy Commandant, Col G. S. Bajaj also joined the Distance Learning Programme. My responsibility was to assist both of them, which I had to do, over and above my routine responsibilities. Periodically, all three of us used to meet and discuss each topic in which I played the role of a tutor. This exercise gave me a great opportunity to go through the subjects thoroughly. Perhaps that is why I have a slogan for all my stu dents, “Problems are opportunities!”

In the meantime, I completed my tenure there and I was posted at the Headquarters, Southern Command for a four-year duration. I decided to pursue a Post-Graduate Diploma in Business Management (PDBM) at IMDR. It was out and out an officers’ batch, to be held during the evening hours. I met the Director, Dr. P. C. Shejwalkar. He told me that admissions were based on an entrance exam and if I scored good marks, he may make an exception to admit me. However, I topped the entrance exam.

Thus, a Subedar successfully taught not one, but many Generals. That, they did not mind learning from a very junior-level subordinate is the lesson that I would to convey to the readers. The Generals had so much respect for my knowledge that they asked me for my opinion about everything. Th us, it is not the position, but the knowledge that you have, that matters

As per the tradition of IMDR in those days, the one who tops the entrance exam becomes the class leader. Now look at my situation: To my bad luck or good luck, Major General M.S Chadha, who was the Major General Artillery and my boss at the Southern Command, had also applied for that entrance exam and got selected. In a batch of 60 students, I was the only one who was not an officer.

So I wanted to go to Dr. Shejwalkar and say, “Sir, thank you very much! I am not joining this course.” How can I?

Before that, I went to the office to ask for the refund of my fees. The admin-in-charge took me to Dr. Shejwalkar who would have none of it. He did not want to let go a bright student so he took me to the class, which was full of officers. Major General M.S Chadha was also seated there. It was very awkward for me.

Dr. Shejwalkar introduced me to the class as Subedar Balasubramanian, who has topped the class, and announced that I didn’t want to join the course as a mark of respect to all the Army officers who would be classmates, and therefore wanted a refund. Major General Chadha stood up and said, “We all are very happy, and we want to congratulate our class leader.” Later, he told me, “It’s a good thing you joined. I have to keep travelling, and now you can teach me on the days I miss the lectures. You can be my teacher.”

Thus began my new engagement of teaching the General. He rarely attended the lectures. I used to come to the institute pedalling my bicycle from home which was about 15 km and then after college, I would cycle straight to the General’s house to help him with the studies. I did not have time to spend with my family as this task would go on till late in the night. My only regret is that I wasn’t able to give my family sufficient time during that period. But I realized that challenges are opportunities.

General Chadha once thought of connecting with all the retired personnel. We both created the concept of ‘Gunner Friends’. We jointly authored an article on this subject which was published with his byline in the Artillery Journal. He received an honorarium of Rs.1,000 which he gave me as a gift. I particularly mention this as an example of the Army’s value for ‘recognition’.

After Gen. Chadha left , Major General, M.S Chhahal took his place and I became a tutor to him too. Subsequently, when he left, General Y K Yadav (who had relieved me from the Army) replaced him and I taught him too. In this process, I perfected my knowledge. I used to relate military principles while teaching management principles as the former is the mother of all management principles today.

Thus, a Subedar successfully taught not one, but many Generals. That, they did not mind learning from a very junior-level subordinate is the lesson that I would like to convey to the readers. Being a pukka fauji, I didn’t even tell my wife that I was tutoring them. The Generals had so much respect for my knowledge that they asked me for my opinion about everything. Thus, it is not the position, but the knowledge that you have, that matters

This entire tenure at the Southern Command demanded much of my time since I had to work overtime to help the Generals with their studies, but I did it happily because of my loyalty and integrity to the Army that I was serving. I enjoyed every bit of it, despite the over-stretched hours. However, it took a heavy toll on my family life and health. But, that is another story...

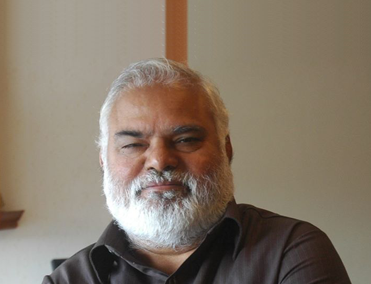

Dr (Col.) A. BAlASUBRANANIAN

editor-in-chief