Issue No.12 / August 16,2015

‘‘For the past 42 years that I have been associated with Pramod as his wife, there is not a single day he has not woken up at the crack of the dawn’’ -Parimal Chaudhari

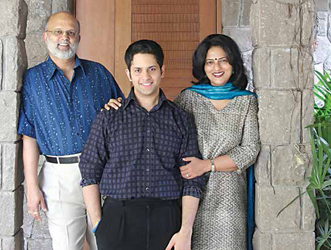

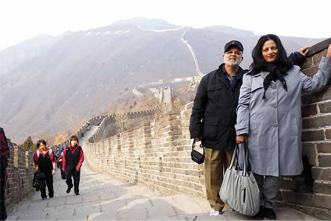

Pramod M Chaudhari, Executive Chairman, Praj India Ltd, and his wife Parimal, who is also a Director on the board of the Rs.1,012 crore biotechnology engineering company in Pune and looks after its CSR initiatives, don’t do anything else together. They take vacations abroad as a couple, but otherwise agree to disagree and go their own separate ways. He continues in hard-core engineering, while she is into journalism, academics, aesthetics and design. And that’s what keeps them together, they tell Corporate Citizen.

Doing everything separately, Parimal Chaudhari laughs, is what has kept their marriage going for more than four decades. “We don’t agree on anything,” she says. “Except to disagree!” adds Pramod. Their disagreements are usually about the act of visiting museums and taking walks around new towns and cities. She loves it, he doesn’t. Yes, they go on holidays together: she is ‘the boss’, deciding where to go; but “he looks out from his window, I look out of mine.” She knows things like art, history and culture better, while he relies on his heart for what he likes. So he accompanies her on tours of art galleries and museums. “But my feet ache!” he complains.

He had every reason to ‘whine’, as Parimal describes it, on their first trip to Rome. During the pre-Google days, doing research on European art before being able to see it was truly a labour of love. A die-hard Bernini fan, she wanted to see most of his work. And Borghese Palace in Rome was something she just had to see. “It was close to the hotel where we stayed. So I dragged Pramod along. The palace has a huge campus and the central building is a long walk. Added to that, it started raining. More frustration! Pramod whined, but I pretended I did not hear him, and kept walking towards the palace building.”

But when they finally reached the magnificent building, it was only to discover that the palace was shut down for restoration work and art cleaning! “I was in tears. I pleaded with the Security Staff in English, but he did not understand a word of what I was saying. Then I spoke in Marathi. I am not sure what it was about the sound of the language or the exasperation on my face, or both, but that did the magic. The security let us in.” Pramod sat on a regal chair in a corner while Parimal went about feasting her eyes on anything and everything she could lay them upon - Bernini’s majestic sculptures of Apollo and Daphne, David, Pauline Bonaparte; paintings of Caravaggio and Correggio – and she had it all to herself, with no other visitors in the palace! “To this day, Pramod remembers the day as one of supreme penance. I have it recorded in my mental diary as a special blessing,” she adds.

Back in 1970, when Pramod popped the question, Parimal replied that she wanted to study; so he waited for three years till she went to the tenth standard. Her second condition was that she didn’t want a baby very soon. He agreed; and even agreed to pay for her education. “I don’t know how he had the gall to say that, even though he had the responsibility of looking after his young sister,” she says. She married him when she was just 17, and went for her PUC examinations wearing a mangalsutra. And though she had studied science till then, because she had aspirations of becoming a doctor, she switched to arts - because she realised that a career in medicine would clash too violently with her husband’s engineering job and dreams.

“Like democracy, marriage is one of the most exploitative and sloppy governing institutions there can be.Expecting it to be blissfully happy is an anomaly’’

Although technically they were three people living in - Pramod, Parimal and Pramod’s sister Usha - the transit guests, both friends and relatives, were so many and so frequent at almost any hour of the day, that they were hardly ever just three at the table. There was no running water in the kitchen. The only municipal tap, which gave water at a low pressure at the best of times, opened n the storage tank. Drinking and cooking water had to be fetched from downstairs. Summers were even more demanding when the water pressure dropped to all-time low and all the water had to be sometimes fetched from downstairs. “I imagine our arms got stretched by a few inches carrying the buckets,” she laughs.

The wada was so close to the centre of Laxmi Road - the main thoroughfare of the old city - that when distant acquaintances came shopping, they pretended to look up Pramod and Parimal; but really they would just come upstairs, complain about the hard climb, use the loo, get treated to a cup of tea or coffee and then vanish, to reappear during their next shopping excursion.

Cooking was a slow, long-drawn process. Burshane gas was a dear commodity, and it ran out without warning - it specially had a tendency to do this precisely when guests were expected. So every once in a while, she had to resort to the slow flame Umrao stove that worked on cotton wicks dipped in kerosene. “My fingers got black, the food smelt of kerosene and chapatis turned out rubbery!” she says.

While Pramod went to work at Bajaj Tempo and then tool manufacturing company Widia India, Parimal managed the home and studied for her B.A in English, Philosophy and Psychology, then went on to earn a post-graduate degree in Communications and Journalism. She excelled in academics, standing first in both.

When Parimal was studying for her B.A at SP College, Usha was working at improving her score to obtain entrance into medical college. “We would get so tired of such guests whose visits interfered with studies, that we often locked our own house from the outside and moved to the room opposite, courtesy our landlord, so that we could study. Of course at the end of the academic year I got a good score at the exams and Usha made it to medical college,” she says.

“We had so little of everything then. Our expectations from life were minimal. For all the ‘less’ in life, what I recall most of that time filled with many guests, was that it was happy times and overall a satisfying period of my life.”

Pramod, however, felt the brunt of married life in more ‘real’ ways. Money kept finding several ways to vanish. His pay was just not enough. Just about three months after marriage, he took up an additional three-hour job to do after his regular job, to augment the income. He never complained, but he was never around the house either. He left home at 7 in the morning and came home at 9 pm. That was the beginning of his workaholic life.

“For the past 42 years that I have been associated with him as his wife, there is not a single day he has not woken up at the crack of the dawn,” Parimal says. “He takes a piece of paper and draws up a ‘to do’ list which can be categorised under four heads:

Meet/visit/Visitors;

Respond/ Follow-up/ Connect;

Plan/ Review /Decide;

Miscellaneous.

Pramod loves packing each moment with activity that leads him to accomplish all this. So there is never a moment free. His idea of a good Sunday is to micro-plan the rest of the week after the proverbial siesta!

Whenever he goes on work with a driving distance of three hours or so with a band of his associates distributed in other cars, he has a few of these people join him in his car for the first 30 minutes and then the other batch of people after that for the next 30/40 minutes, depending upon the work concluded and so on. All through his travelling time, he uses his car as a mobile office. Not even a moment is lost over the travel. Even the time at international airports, before and after long flights, is stuffed with appointments where he has to complete some or other kind of work-related discussion or an assignment.

More often than not, holidays are also interlaced with work. In the early years, this obsession with work irritated and even offended Parimal. But now, she uses these work breaks to walk around and see museums on her own.

But two distinct memories well up when Parimal remembers their holidays together. Both have to do with mesmeric experiences with Nature.

Travelling in and around Coorg, they were at a friend’s place - the quintessential sprawling Coorgi coffee estate, with a plush home and meandering gardens. It was dusk and the friend ushered them, along with the other guests, to sit around an old well there. “We were intrigued by such a strange request. Soon, there were small birds that began hovering in a spiral over the well like several aircraft wanting to land in the same place and at the same time and not wanting to crash. As if waiting for the right cue, one of them dived into the well, then the next, then the next and soon there were over a couple of thousand birds that had dived into the well; never at the same time, but one after the other, in a single sharp drop. The way they swept in was like in answer to a calling coming from the cavernous well,” she says. “According to our host, the same birds came each evening at the same time and used the shelter. At day break they all rose and took flight into the sky; again one after the other and never crashing.”

But nothing can compete with the mesmeric moment they had with the Moon bang on the Equator amidst the grasslands of Kenya, devoid of any electrical lights for miles and miles.... as it rose up like a large luminescent ball from the earth over the horizon. “Words can never describe it to see the moon rise from the earth rather than mountain or building. The sight would beat any Spielberg movie set!” she adds.

As Parimal continued to progress on her career path – learning Marathi and getting articles in that language published in a range of newspapers and magazines like Sakal, Maher, Kirloskar and Stree – Pramod was busy building the new company he had started in 1983-84 after telling his erstwhile boss, “Sir, I want to be in your chair. And since only one of us can be in that chair, it is better that I go.” Says Parimal: “He was a workaholic of the first order!” It was her standing as a journalist that helped him get a telephone connection for the budding Praj.

Motherhood gives focus to whatever else you are doing... Fatherhood, obviously, didn’t – one day, Pramod forgot to pick up the baby from the crèche -Parimal

Then, in December 1986, their son was born. And now they both had babies to look after – she had Parth, he had Praj. “Even 12 years after marriage, it was a foolhardy decision,” she says. “But you do wild things when you are young.” She continued studying, attending evening college at Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth. Here, too, she stood first in the deemed university with an aggregate of 72 per cent in her ‘integrated course’, keeping her top-scoring record unbroken. “Motherhood gives focus to whatever else you are doing,” she says. Fatherhood, obviously, didn’t – one day, Pramod forgot to pick up the baby from the crèche: “I could have killed him!” Parimal says.

She however continued in journalism while Pramod was working to build Praj - taking it to a position where it has a solid reputation of having set up ethanol plants for customers in India and around the globe, and morphing it into a global process engineering and biotechnology company with major interests and achievements in research and development. While 95 per cent of the company’s business was ethanol and breweries till just five years ago, emerging businesses have now grown to almost of a third of its total portfolio.

Parimal went to the University of Pune’s Department of Communications & Journalism, where she had studied, to start work on a Ph.D but was roped in to conduct the examinations. So she joined as a teacher, for a six-month tenure in a reserved-category post – but it became ‘open’ and she continued for six years. In 1991, she went off for six weeks on a Rotary Club exchange programme for media studies, visiting Austria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary; then a television workshop in Delhi, followed by a Fulbright Scholarship in the USA in 1993. Keeping to her reputation for academic excellence, she finished the required 35 credits in just nine months – while back home, Praj went public and its Initial Public Offering was subscribed a whopping seven times.

At Syracuse in the US, Parimal met another Indian, also a Maharashtrian: Sanjay Dabke, and they became friends. Back in India, they teamed up to start their own company, Turtle Communications, where they made educational and corporate CD-ROMs. They also made short films on social issues, and two series of 12 each on finance and traffic issues. Today, Turtle continues to create video films for non-governmental organisations to make fund-raising presentations to foreign agencies, corporate bodies launching initial public offerings and other clients. Why 'Turtle'? "In 1997, when I made my first film for the US FDA on ayurveda, for a company that wanted to launch herbal medicines in the US and the UK, I wanted a catchy name, one that would make people ask just that question!" she laughs. "Also, it's a cross-cultural name; and I think an amphibian connotes creativity and benignity.

In 1999, she went to Cambridge – and loved the place. She applied for, and got admission to a one-year course on script-writing and creative writing. “I was bicycling all over the place, like any other student,” she recalls. Parth, whom her parents and in-laws looked after when he was younger – so that he was never without supervision – was now old enough to go to hostel. One of her most cherished memories of her Cambridge stint is of having met Edward de Bono; she studied lateral thinking, and is now a certified trainer in the subject.

Around the same time, when the global economic upheaval affected business fortunes around the world, Praj began using a sociometric tool to measure people’s abilities and match them to their work in the organisation. The company was big enough to try out this new system of innovation and thinking skills; and this generated a lot of interest in it at the turn of the century. Four years into the new millennium, Praj effected a turnaround and crossed its long-awaited milestone of a Rs.1,000-crore turnover.

In 2009, I initiated a drive to encourage intrapreneurship, which is entrepreneurship by employees within an organisation; each treats their area of responsibility as their own business-Pramod.

Then, in 1995, Pramod decided to go to Harvard. “My wife was studying and studying, and I was stuck with only an IIT degree!” he jokes. He also invited Parimal to join the company’s Board of Directors: “She had a variety of skills, which helped increase the family approach.” Adds his wife herself: “I helped in feminising the engineering space, bringing in gender parity.” Today, she is also on the Managing Committee of the Praj Foundation, which they set up seven years before the government made CSR mandatory, and is Chairman of the company’s CSR Committee.

We were quite ahead long before compliance was needed,” adds Pramod. “For us, giving started very, very early: Infosys got into it after it became a Rs.3,000-crore company, we were just ₹ 600 crores.” Parimal also initiated an Art Foundation for Marathi language, drama and cinema.

How do their philosophies about work and marriage differ? “For Pramod work is everything. For me I work so that I can do everything else,” Parimal answers. She has, however, never worked for money except when she was a journalist. Her views on marriage are probably the most interesting: “Like democracy, it is one of the most exploitative and sloppy governing institutions there can be. But the other institutions are far worse. Expecting it to be blissfully happy is an anomaly. It can be treated like a good negotiation: one plods, navigates, wins some rounds, loses some rounds and eventually, one hopes, one cumulatively wins!” she adds.

Pramod, an ardent promoter of renewable energy, is on various committees including the Committee on Development of BioFuels, Planning Commission, and the Committee on Project Exports constituted by the Government of India and Confederation of Indian Industry/Exim Bank. Pramod is Chairman of CII’s National Biofuels Committee. As part of the global bio-energy movement, he says he is “getting out of the confines of Pune and India”. And sustainability is part of Parimal’s CSR, strengthened by his own efforts. Praj has ridden its technology into areas like zero liquid discharge (ZLD) systems to help clients clean up their act and fight their pollution problems. After the Madras High Court ordered the closure of 720 dyeing units in the textile hub of Tirupur in Tamil Nadu to protect the Noyyal river, the company commissioned a 700-kilolitre-per-day (klpd) ZLD unit for Veerapandi Common Effluent Treatment Plant Pvt. Ltd (CETP). It began by setting up a pilot plant, which experts from the Tamil Nadu Pollution Board, Anna University and IIT Madras okayed; then a full- fledged plant. The technology comprises innovative multi-effect evaporation and crystallisation to solve the problem of groundwater pollution due to discharge of colorants. The Praj process also enables the recovery of process condensate and salts, which are reusable in the textile dyeing units. The company has since got repeat orders for larger projects.

The company’s work in other bio-based products and processes besides bio-fuels has been recognised by the Association of Biotechnology Led Enterprises (ABLE), which gave Pramod its tenth anniversary award in the 'BioIndustrial' category last year. The company’s R&D centre Praj Matrix, set up to accelerate the development of bio-based technologies, is the first of its kind in the tropics conducting research on various bio-based processes right from laboratory to pilot scale under one roof.

Praj also offers home-grown turnkey solutions to cater to the biodiesel market, through a separate division set up to promote this business line.

The Chaudharis have taken Praj beyond CSR into what they call PSR, personal social responsibility - under which employees, their wives and children get engaged in community action. “For example, we took a batch of them to a forest to work with, and help, the local people,” Pramod explains. “We also went to clean the backwaters of Pune’s Khadakwasla dam.” Every year, an employee gives eight hours of his or her time to the PSR project, which adds up to a staggering 10,000 person hours.

Pramod has done a lot for his alma mater, donating two biotechnology laboratories for cell culture and bio-processing. “He surely cares about IIT-B in a big way,” Parimal says. “He has given substantial financial contributions for setting up the Pramod Chaudhari Chair for Green Chemistry and Industrial Biotechnology there. Together, we have also financed and set up the Parimal and Pramod Chaudhari Laboratory for Cell Culture.

He is also associated with many incubation activities through the Society of Innovators and Entrepreneurs, SInE, which is a business incubator unit at IIT-B. “A balance of innovation and entrepreneurship is the way forward,” he asserts. Adds Parimal: “He is expressing his penchant for innovation and entrepreneurship through SInE by being its Pune chapter, making space and giving time to this activity.”

Credited with the introduction of the continuous fermentation process in the Indian distillery industry, Pramod has made his company a world leader in molasses-based ethanol plant and technology, with clients in India, South East Asia, Africa and South America. As Parimal says in the book: “He is a man who knew what he wanted and worked to get it.”

Doing everything separately, Parimal Chaudhari laughs, is what has kept their marriage going for more than four decades. “We don’t agree on anything,” she says. “except to disagree!” adds Pramod.

Proof: he has created a successful company despite a 19-month disaster when he launched his entrepreneurial career as co-promoter of Rapicut Carbides. “That was a different learning experience,” he says. Back in 1983, Chaudhari “got into the trenches” in what was the 'war' of his life. He suggested to Alfa Laval management that they join hands, but was rebuffed. So he decided to take on the multinational in direct competition: with just a small rented table space and repeated trips to the Mahratta Chamber of Commerce and Industry for fax and teleprinter services. Talking of his 'strong inner belief ' that alcohol had a big future, he says in what is apparently an unintended pun, “This spirit sustained me.”

Pramod needed that spirit, through the 'heartbreak' of a terrible seven-year patch that Praj went through from 1995 to 2002. But he went on to build his company into an inspiration for millions of young technopreneurs. And Parimal, whatever the two say, is marching with him on every step of his way.

By Sekhar Seshan