Issue No.13 / September 16,2015

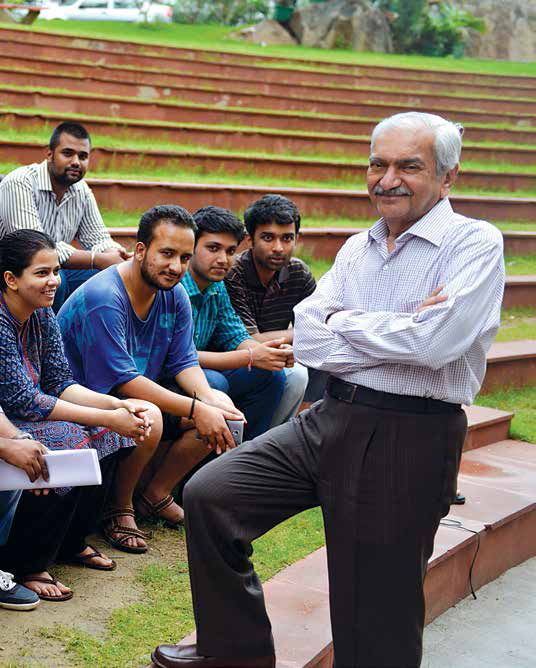

Having spent 33 out of his 45 years of teaching econometrics at the premier Indian Institute of Management-Ahmedabad (IIM-A), Dr. Bakul Dholakia is best known as its most courageous, energetic and visionary director (2002-2007). He is also known for his legendary battles with the then political establishment at the Centre to vigorously espouse the cause of IIM’s financial autonomy. Recipient of the Padma Shri in 2007, he is acknowledged as a colossus among management gurus under whose leadership IIM-A emerged the top ranked B-school in India and Asia-Pacific by every consecutive survey, conducted by respected business publications like Business Today, Outlook and The Week. An institution builder who is known for his penchant for calling a spade a spade, he subsequently joined India’s fastest growing corporate group, the Adanis (2007-14), to establish their world-class Adani Institute of Infrastructure Management, Adani Knowledge Centre and Adani Institute of Medical Sciences in Bhuj (Gujarat). A gold medallist and Doctorate in Economics from Baroda University, the irrepressible professor worked in every committee of the IIM-A and even now gives the impression of being a man with no full stops in life. Having guided 20 PhD students at IIM-A and served as a board member of the Reserve Bank of India (1993-2001), Dr. Dholakia is currently working as the Director-General of the New Delhi-based, high-profile International Management Institute (IMI). For the past nine months, he has been making every possible effort to take IMI to new heights of excellence, giving dynamic thrust through his strategic thinking. In a candid conversation with Corporate Citizen, he shared his thoughts on a wide range of subjects while giving glimpses into his exceptionally stimulating journey. Excerpts:

Here was a civil hospital run by the Government of Gujarat. It was not running well. When the earthquake hit Bhuj in 2001, the civil hospital got destroyed. Atal Bihari Vajpayee was the PM and he went to Kutch and promised that not only would this be rebuilt from the PM’s relief fund but a medical college would also be created in the same campus. Nine years passed, nothing happened, so the Adani group took up the responsibility. The idea was to take over the civil hospital and run it. There are many examples of corporate hospitals in this country.

The profile of IMI is similar to that of IIMAhmedabad. It also runs an MBA program, a one year executive program, PhD programs, does consulting – so it has a classic business school profile

but not a single one where a civil hospital is run like a corporate hospital! My motto was: quality healthcare to the poor at civil hospital prices. Serving vulnerable sections of society was the objective. If a poor guy gets a heart attack, why should he not get a bypass surgery done by the best doctors who only corporate hospitals can afford? So, this was a Corporate Social Activity and that was what excited me. I wanted the focus of its medical education on research. I wanted to create a post-graduate centre of excellence at this medical college because Gujarat medical colleges were not doing much research. That was what I was able to create there. It’s comparable to AIIMS in Delhi. That is the reason I took up that project.

Late RP Goenka, founder of the RPG Group, created this institute in 1981 with a vision of shaping global leaders of tomorrow. Now his son, Sanjeev Goenka is managing it. He wanted me to turn the IMI around. Upgrading it to a global brand was the challenge at IIM-A. Here the challenge was to turn it around, both financially and operationally.

This is a different experience. IMI Bhubaneswar and Kolkata are new institutes, just coming up, but IMI Delhi has been in existence for 30 years. However, the financial position is not so good because my predecessor went for capacity expansion of executive education, and therefore created a lot of infrastructure. The Society did not have money, so he borrowed heavily from a bank. A huge loan then needed to be serviced but the markets went down, because there was recession. So, executive education also went down. Managing finances, repositioning this institute, and making its position felt globally are issues I have been brought in to deal with.

In many respects, the activity profile of IMI is similar to that of IIM-Ahmedabad. It also runs an MBA program, a one year executive program, PhD programs, does consulting – so it has a classic business school profile. But the question was about refocusing each of these. For instance, the executive education programs and MDPs were largely sponsored; the banking and finance program was not doing well; we didn’t have too many partnerships; existing partnerships were not active. So it was a turnaround case – introducing and managing change.

There are different aspects of leadership, they all require different ways of leading. Here, it was about changing the culture; introducing systems and processes; changing the vision; upgrading the profile of the institute and giving it financial stability. This was the first time I was managing an institution which had a huge debt.

The institute had no formal budgeting system.Most people running programs did so without preparing any sort of budget. It’s unbelievable, but that’s how it was. So, I introduced an approval process that required people to apply their mind to allocating resources to different activities. They had introduced a twoyear MBA in banking and insurance. But that decision was taken in a random manner – there was no project report, no feasibility study. No wonder, it was not doing well. Faculty was recruited without a formal recruitment process. There were a whole lot of systems and process related issues too.

‘There are different aspects of leadership, they all require different ways of leading. Here, (at IMI) it was about changing the culture; introducing systems and processes; changing the vision; upgrading the profile of the institute and giving it financial stability’

The problem with placements at IMI was that there was no connect between executive education and research the institute was doing, and placements. In a standard business school like the IIM-A, all of our PGPEX is done for the private sector. That enables us to showcase our abilities to senior executives of the private sector and it comes back to you in the form of recruitment. We do a lot of consultancy for the private sector, which helps with better case material in the class room, experiential learning for faculty, upgrades the quality of teaching and gives you better placements. So, between research, consultancy, executive training, and a two-year MBA program, there is a direct connect. But here at IMI, there is a total disconnect. All the activities are public sector oriented. Consulting is for the public sector, so is training. The public sector, however, does not come to private business schools for recruitment. They have their own systems and do not offer good packages. I’m trying to correct it.

I’ve been here for hardly nine months, and the green shoots are very positive. So, I’m hopeful.

I am trying to streamline the recruitment process. Staff members did not have KRAs (Key Responsibilty Areas), I have defined them. The fundamental problem in higher education institutes is that the administrative support staff does not have the required skills. So I started inhouse training programs for my administrative employees. It made a lot of difference in their skill set. I made it compulsory for my staff to attend ongoing executive programs as participants. Then I sent 20 officers on an overseas trip to show them how international institutions work. I plan to apply many of these experiences here. But managing change is a painful process.

B-school surveys were not very fashionable till 1994-95. There was no rat race for rankings. In fact, the country liberalised its economy in 1991 and it was only after that that placements came into fashion and aspiration levels started going up. The integration of the country with the global market place happened; international collaborations also started happening. Global branding was not something people would even think about in the ‘80s but by 2000, change was coming in. In 2000, Business Today conducted a perceptual survey of business schools and IIM-A was ranked number one. But in 2002, when they subjected to power control, our annual reports were placed in the parliament, our budgets were approved by the board and seen by the ministry, and our accounts audited by CAG, but once the budget was approved by the board, individual items of the budget should not be subject to further approval by the ministry, which was what was happening. If I have to send my faculty members abroad for conferences or if I have to open a new centre, I can’t keep waiting for ministry approvals. If I need to get approvals from the GOI for every strategic action or plan, then I was not interested in the job. That’s what I told the selection committee. My vision was of not just administrative autonomy but financial autonomy as well. The key element in this strategy was to not take money from the government, so that the moral authority for government control disappeared completely. What really happened when you rejected the government’s Rs.10-crore offer? Well, I was called for a discussion in Delhi. They asked, “How can you do this? We want to give you money. Take it.” I said, “No, you want to give me money but in turn, you want every item of my expenditure to be controlled and I’m not interested in that. I will not come to you, even for repeated the survey, IIM Bangalore was ranked number one and IIM-A number two. There was another survey which also ranked IIM-A at number two. So, by 2002, the impression got created that IIM-Ahmedabad, Bangalore and Calcutta were almost on par. It was in that environment that I became the director. I said, “We must not only unequivocally establish ourselves as the best B-school in the country, but simultaneously emerge as a global B-school with international recognition.” As they say, it is the art of the possible. I studied the functioning of the best B-schools abroad and made a presentation to the board that these were the strategic initiatives that were required, and convinced them. I also did a SWOT analysis of the institute. In those days, it was not common for the directors of the institute to make formal presentations to the board. I started the practice of power point presentations. In 2002, Dr. Narayana Murthy of Infosys became the Chairman of IIM-A. It was under his chairmanship that I got appointed as its director. We worked together for four and a half years and made sure that IIM-A emerged on top and stayed ahead of the rest of the B-schools.

But here at IMI, there is a total disconnect. All the activities are public sector oriented. Consulting is for the public sector, so is training. The public sector, however, does not come to private business schools for recruitment

I felt that autonomy was a real problem because there was too much government interference in our matters. My SWOT analysis mentioned it as a major threat. My diagnosis was that because IIM-A depends on the Government of India (GOI) for its funding, it was in a difficult situation. In those days, we used to get about Rs. 10 crores by way of annual recurring grants and around Rs.2 crores for capital expenditure. I was of the view that the institute should manage its activities from its own internal resources and not depend on government funding. Let them use that money either for creating new IIMs or doing something else, but we should be self-sustaining.

When I took over as director, the government had given us grants to create a corpus of a little under Rs.100 crores, and in those days the interest rates were very high. We used to get around 12 per cent interest for long-term deposits. That basically meant you earned about Rs.10-12 crores interest and about Rs.12 crores grants and the total budget of the institute was hardly Rs.40 crores, which basically meant that 60% of our money came from grant and interest. So, I argued, we were more like a portfolio management company. We were managing funds of Rs.100 crores and our core activities were not contributing half of our revenue, only 30-40 percent. So, we needed to review it. At the very first board meeting after I took over as director, I proposed that we politely say no to government grants.

My strategy was that while it was okay to be subjected to power control, our annual reports were placed in the parliament, our budgets were approved by the board and seen by the ministry, and our accounts audited by CAG, but once the budget was approved by the board, individual items of the budget should not be subject to further approval by the ministry, which was what was happening. If I have to send my faculty members abroad for conferences or if I have to open a new centre, I can’t keep waiting for ministry approvals. If I need to get approvals from the GOI for every strategic action or plan, then I was not interested in the job. That’s what I told the selection committee. My vision was of not just administrative autonomy but financial autonomy as well. The key element in this strategy was to not take money from the government, so that the moral authority for government control disappeared completely.

Anyway, I had already anticipated all this. I remember the first ever idea as soon as I took over as director was that we ought to have a meeting of IIM directors – let us share our common issues and concerns. I had created an informal forum of IIM directors. There were six IIMs when I took over as the director, but no such forum. There were ego issues because people did not get along. The first-ever meeting of IIM directors was held in Mumbai at Narsee Monjee Institute because a neutral venue was required! Thereafter, each IIM hosted, and we used to meet every quarter. That forum stood by me in good stead when the storm really came. They passed this order of fee cut in February 2004 and four of the six IIMs fell in line. They accepted the dictat. However, Bangalore said we will do what Ahmedabad does, and I said, I’m not going to sign it. The famous threat from the ministry was: sign or resign! I said I’ll do neither. You need to sack me if you have the guts. And then it became a raging battle. I perceived it as a battle for autonomy.

Certain sections in the Memorandum of Association were grey areas. For instance, fee determination was a grey area; foreignpartnerships were a grey area. However, salaries of faculty were fixed in black and white by the government. So, I could not pay market salaries. Similarly, foreign campus was not a grey area. I could not have a foreign campus. So, it was a question of interpreting the MoA and I always argued with my board that autonomy is not to be sought, it is to be taken within the purview of the written rules. Anything which is not clearly spelt out in the MoA is therefore my area of freedom. So, I entered into tie-ups with foreign institutes. I conducted activities abroad. The MoA was silent on consultancy, so I framed my rules, liberalised it so much that it became my instrument for retention of faculty. When I took over the previous year, 15 faculty members had left IIM-Ahmedabad. People would take leave and then go on exodus. However, in my entire tenure of five years, I granted leave to ten faculty members and nine of them came back. It takes a lot of effort to recruit faculty, so you must retain them. I liberalised the terms and conditions of consultancy, so that the gross pay package of the faculty shot up. I gave liberal research grants and simplified rules for travel for overseas, and I led by example.

When my term ended, I was quite popular with the board, alumni, society members, faculty and students, and there was a lot of pressure on me to take a second term. I was only 60 and the retirement age was 65. So I had five more years to go and could have taken the second term. But at IIM-A, we always had a change of leadership every five years which I thought was very healthy. I remember the HRD ministry secretary called me up to find out if I was still interested. But I said, no, thank you very much. The board also asked me, and I refused again.

My vision is to make IMI the best private sector B-school in the country. So long as IIM Ahmedabad, Bangalore and Calcutta are there, to become the best in the country is very difficult

Yes. IMI already has AMBA accreditation and always go for improvement. If you want a global status, you must have global agencies recognising you. They agreed, and thus we went for EQUIS (European Quality Improvement System) and became the first B-school in India to have got it in 2008, just a few months after I left IIM-A.

When I launched our one-year program I told my faculty I need international participation. My first batch had 30 percent foreign participants. IIM-A became the first B-school in India that went and conducted interviews in London and New York. I had so many applications, but this cannot be done in a two-year program. The reason is very simple – two-year program admissions are through CAT. How will foreign participants write CAT? I wanted to make CAT go global that’s why I wanted it to go online and become an international brand like GMAT, but with the then set up of the government, it was a challenge. You need a different vision for doing that. For our one- year program, the selection instrument was GMAT. In fact, the gold medallist of my first such batch was a British national.

NRI-sponsored candidates are accepted in the two-year program. They give GMAT but what happens is that at IIM-A, the GMAT cut off has to be parallel to CAT. Now, in CAT, we take 99 percentile and 99 percentile GMAT will get admission anywhere in the world. So, why will he come to Ahmedabad? I kept on telling people, if I created a foreign quota, my MBA admissions would get thousands of applications but I had enough quotas and I did not want to create one more.

There is no connect between the cost of education and these fees. It is not justifiable. It is a vicious circle. You require to pay faculty well in order to get good quality faculty. It is true that only good quality faculty can drive good quality education, but even with reasonable market-oriented pay packets for faculty, and other world-class infrastructure cost and all that, I still don’t think the cost of education per student per year is more than Rs. 6 lakhs or so per annum, including some surplus to invest in research and other things. Even the Supreme Court allows 15-20 percent surplus. So if you assume Rs.6-7 lakhs as the cost, then Rs.8-9 lakhs per year is justified. In private institutions, the entire investment is borne by them, not so IIMs. Which IIM has purchased land? Nobody. The basic infrastructure of all IIMs was created by government grant. So you have no capital cost. Hence, to that extent, the cost of education at IIMs should be less than the cost of education at comparable private B-schools. But people have gone overboard. Currently our fees at IMI are Rs. 14.5 lakhs for two years, a little more than Rs.7 lakhs per annum, which is significantly below what IIMs are charging. Today, even newly set-up IIMs are charging more than Rs.10 lakhs for two years. The entire capital expenditure of the newly set-up IIMs is given by the government, and they also get significant annual grant which covers faculty cost and everything concerning infrastructure. So, that’s what it is. Fees in the established IIMs around Rs.20 lakhs plus is certainly pretty high.

Firstly, consciousness towards the society and the desire to give something back to society is not a matter of teaching and training. Just as ethics cannot be taught, so is culture. You imbibe your culture.

‘The fundamental problem in higher education institutes is that the administrative support staff does not have the required skills’

IIMs are postgraduate institutions. The average age of people who come there is 22-23. At this age, you can’t be taught values. Your values have already been moulded. Your approach to life has already been determined. So, these are things which have to be done at the level of the school which is where the personality really develops. Secondly, the cultural position and ethical values of a child or an adult are, to a large extent, determined by the family and the environment he/she comes from.

Having said that, business schools should do what they can. This is where high fees become a problem because then it becomes a question of return on investment. If I have acquired education by paying Rs.20 lakhs and to the Rs.20 lakhs I add Rs.10 lakhs more because if I had not acquired the education, I would have been working, and that would have been my earnings, the cost of education at an established IIM comes to Rs.30 lakhs. It is quite natural that he wants to recover these Rs.30 lakhs as fast as possible. That is the reason why there is so much focus on packages. This is the crux of the matter. Now, there are two things business schools can do. One, create the consciousness to do something for the society and also inculcate the entrepreneurial spirit. That’s what I did when I was at IIM-A. I focused on entrepreneurship, created frameworks where the students could opt out from placements to pursue entrepreneurial dreams. I also encouraged students to at least take their summer internships at NGOs, so that they became responsive to societal problems.

We introduced courses that opened them up to the society. Like, for instance, one of the courses in the second year elective in my time was called ShodhYatra. Prof. Anil Gupta used to run this. He would take students to rural India and they would spend two to three weeks there. It’ s like discovering true India. Similarly, we had a compulsory course on the Indian social and political environment where they would basically understand Indian society and culture. But that was all. You can’t force a man to be ethical. You can take a horse to a river but you can’t force it to drink.

Besides my wife, I’ve two daughters, highly educated and settled in Canada. I’ve a brother who is a distinguished professor at IIM-A. He has been there for the last 30 years. My wife has been teaching at a higher secondary school. She has also retired now. Right now, she is with my daughters. She stays partly with me and partly with my daughters. Both my daughters are working. My elder daughter is married and has two sons while the younger one is unmarried.

I’d just like to be remembered for the difference I made at the institutions where I worked.

By Pradeep Mathur